If i had to pick one musical scale to take with me to a desert island, and the only choice was between an elegantly crafted Schoenbergian twelve-tone row and a plain old blues scale, I’d quickly grab the blues scale before they tossed me off the ship.

The noble musical experiments of Schoenberg and other modernist composers were enormously influential within academic and concert circles. But while these august types were busy out-moderning each other, blues and other African-derived musical styles — jazz, rhythm and blues, and hiphop, to name only several — colonized the world, holding sway in a manner akin to the complete cultural dominance of Italian music in Europe from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

February is Black History Month, and this column is going to depart from its usual listings format to explore this phenomenon in some depth. Black History Month was originally conceived as a week-long celebration encompassing the February birth dates of American abolitionist Frederick Douglass and president Abraham Lincoln. In modern times it has become an occasion for the people of the African diaspora to celebrate their history of struggle and triumph, and their formidable achievements.

One of these achievements is the degree to which African-derived techniques are part of the DNA of popular music. When yet another well-scrubbed American Idol contestant launches into a showy fusillade of vocal melismas, they are echoing (but rarely surpassing) the vocal work of Stevie Wonder. (Also a notable composer, Wonder’s work is so innovative that it has barely been picked up by anyone, but that is another story). Any good professional bass player builds on the nimble, inventive lines of genius Motown bassist James Jamerson. Fletcher Henderson’s swing orchestra arrangements are the Well-Tempered Clavier of jazz orchestra studies. In a musical sense, every month is Black History Month, whether we consciously perceive it or not.

Classical musical studies largely continue to ignore African-derived musical techniques, leaving graduating students unequipped to deal with large areas of musical endeavor and employment. It is as if drama students were taught to execute Shakespeare, Racine and classical Greek drama, but were sheltered from Beckett, television and film. Classical vocal students grapple with the demands of 20th century vocal writing — often absurdly ill-wrought for the voice — but are given no thorough stylistic understanding of jazz or blues.

It is in this area that choirs have been something of a vanguard. Choral groups often have to be stylistically diverse, and classical choirs have been executing choral arrangements of spirituals since the beginning of the last century. Singing African-derived music with European technique and aesthetic remains a trap, but choral directors are increasingly applying performance practice techniques to this music, doing the listening, research and technical practice that leads to more authentic and appropriate performances.

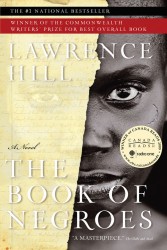

Toronto’s Nathaniel Dett Chorale, founded in 1998 by Brainerd Blyden-Taylor, has provided strong leadership in this area. Named for an African-Canadian, Drummondville composer who made his career in the USA, the NDC has consistently programmed interesting and unusual works. On February 14 they team up with writer Lawrence Hill for “Voices of the Diaspora: The Book of Negroes.”

Toronto’s Nathaniel Dett Chorale, founded in 1998 by Brainerd Blyden-Taylor, has provided strong leadership in this area. Named for an African-Canadian, Drummondville composer who made his career in the USA, the NDC has consistently programmed interesting and unusual works. On February 14 they team up with writer Lawrence Hill for “Voices of the Diaspora: The Book of Negroes.”

The concert is named for Hill’s book, which is named, in turn, for an actual document created in 1783. The Book of Negroes was a list of 3000 African slaves, evacuated by the British from the USA to Nova Scotia, which was still a British dominion. Hill blends historical incident with a wrenching story of a slave family trying to stay together in the midst of political tumult and violence.

The Book of Negroes has been an international success for Hill, who will read excerpts from the novel, interspersed with music from the NDC. Works by Dett himself will be featured, along with music by Haitian composer Sydney Guillaume and Canadian composer Brian Tate. Jazz pianist Joe Sealy will also perform excerpts from his celebrated Africville Suite, that pays tribute to the African Nova Scotians of Africville, who contended with prejudice and neglect until the final destruction of their community and forced eviction of its residents in the mid-1960s.

Hill’s and Sealy’s involvement in this concert highlights another problematic issue, which is the degree to which Canadian art must fight for space in Canada. Sharing a common language and history, our cultural landscape is swamped by our American neighbour, and while most musicians (and film-goers and politicians) yield willingly to the artistic tidal wave, it is always heartening to see Canadian artists carve out a space for their own ideas and dreams.

(A personal note: In grade 9 English, my daughter, along with too many other Ontario high school students, is currently being subjected to Alabama-born writer Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. This book — the literary equivalent of warm milk and cookies for self-congratulating American progressives of a bygone era — should have been retired from our curriculum years ago. Lawrence Hill’s trenchant thoughts on the subject can be read here: www.thestar.com/article/684933.)

Hill’s The Book of Negroes — fiction informed by ground-breaking research — puts him in the fine Canadian tradition of Pierre Berton, who wrote history with the sweep and dash of good fiction. As Berton did, Hill is “shining a little light” to help his fellow Canadians understand more about themselves.

Other concerts of interest on the horizon:

On February 23, the Orpheus Choir of Toronto performs a free noontime concert at Roy Thomson Hall in a concert series that is one of the hidden gems of the Toronto choral scene.

On February 24 and 25, the Soweto Gospel Choir visits the city. Check out this clip:

On February 25, the Scarborough Philharmonic Orchestra teams up with the Toronto Choral Society to perform Brahms’ Requiem and Schubert’s Eighth Symphony, the “Unfinished.”

On March 3, the Jubilate Singers perform an all-Argentinian programme: tango composer Astor Piazzolla, Carlos Guastavino and others. The concert will also feature tango dancers from Club Milonga, accompanied by the Tango Fresco ensemble.

Also on March 3, the Toronto Chamber Choir performs “Gibbons: Canticles & Cries.” Orlando Gibbons was one of the greatest composers of the English Renaissance. Not to be missed!

Ben Stein is a Toronto tenor and theorbist. He can be contacted at choralscene@thewholenote.com. Visit his website at benjaminstein.ca.