The term avant-garde has come to mean art on the edge – work that is provocative and disturbing. Many people are not aware that avant-garde was originally the military term for soldiers whose task was to scout terrain ahead of an advancing army. To be a member of the avant-garde, therefore, was to be at a higher risk of first contact and combat than other members of the force, and like many that are first over the top in any combat situation, members of the avant-garde were not expected to have a high survival rate.

The term avant-garde has come to mean art on the edge – work that is provocative and disturbing. Many people are not aware that avant-garde was originally the military term for soldiers whose task was to scout terrain ahead of an advancing army. To be a member of the avant-garde, therefore, was to be at a higher risk of first contact and combat than other members of the force, and like many that are first over the top in any combat situation, members of the avant-garde were not expected to have a high survival rate.

Frequently, the artistic avant-garde faces a kind of annihilation as well; not death, thankfully, but the loss of their cutting-edge relevance. Their innovations are subsumed into the mainstream, their work ceases to provoke and the public moves on to new outrages and diversions.

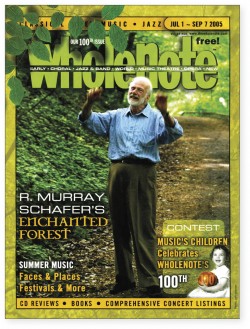

In artistic terms, what happens to a member of the avant-garde who has survived their encounter with a hostile or receptive public and lived to tell the tale? Do they become venerated elder statesmen, losing their indie cred as they join the establishment, or do they stay on the cutting edge? Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer has enjoyed both rebel status and critical success, amassing a performance history that many composers must envy. His work has never been mainstream, but it has extended beyond the small contemporary music audience to which many composers find their work consigned.

In artistic terms, what happens to a member of the avant-garde who has survived their encounter with a hostile or receptive public and lived to tell the tale? Do they become venerated elder statesmen, losing their indie cred as they join the establishment, or do they stay on the cutting edge? Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer has enjoyed both rebel status and critical success, amassing a performance history that many composers must envy. His work has never been mainstream, but it has extended beyond the small contemporary music audience to which many composers find their work consigned.

Schafer has been credited with inventing the term “soundscape.” It may be hard for young musicians and their audiences, accustomed to opera productions in vodka bars and symphonies on bicycles, to appreciate how revolutionary it was for Schafer to mount his productions in forests, lakes and other spaces beyond the concert hall. But while there can be a gimmicky quality to some non-traditional staging, Schafer’s work was always rooted in a simple but profound belief that (to paraphrase conductor David Fallis) music changes depending on how and where it is heard. Schafer’s staging needs, his graphic scores and sound innovations were a passionate attempt to get both performers and audiences to listen with fresh ears.

Schafer has been scathing in the past about certain concert music traditions that he finds stultifying. I read one memorable essay in which he compared the classical piano itself to a prostitute. Whether you agree with this or not – I’m not sure that much is achieved by denigrating keyboard instruments or sex workers, either on their own or juxtaposed – it certainly made for provocative reading.

But Schafer’s ire was partly a reaction to what he regarded as the ossified concert culture which unfortunately remains with us still. Schafer’s approach to actual musicians, and the concert audience itself, has been anything but stern and insulting. On the contrary, it has often been playfully generous, notably in his works for children. Unlike some avant-garde artists, Schafer’s lack of contempt for the audience, and his clear desire to connect using musical language that is accessible as well as challenging, has been in part responsible for the positive response to his work.

And so, despite avant-garde aspects in Schafer’s music, I have always thought of him as the last Romantic, a Canadian Mahler of the North. While his tonal language uses extended harmonies and non-traditional soundscapes, his music is rooted in the techniques of earlier eras, including his ability to write a good old-fashioned catchy melody, the most deceptively simple and undervalued of a composer’s skills. Schafer’s fascination with nature, and his frequent depiction of metaphysical battles between good and evil, connect his work to traditions that seem at odds with this era’s self-referential irony and arch diffidence. I would urge both those of advanced and conservative tastes to give Schafer a listen, if they have not done so before.

This month brings the opportunity to do just that, by attending a performance of one of Schafer’s most ambitious works. In June, Toronto’s Luminato Festival will mount a new production of Schafer’s Apocalypsis. This is the first time that the work will be heard in its entirety since its 1980 premiere in London, Ontario.

This month brings the opportunity to do just that, by attending a performance of one of Schafer’s most ambitious works. In June, Toronto’s Luminato Festival will mount a new production of Schafer’s Apocalypsis. This is the first time that the work will be heard in its entirety since its 1980 premiere in London, Ontario.

Apocalypsis is a two-part work. The first half is based on the Book of Revelation, the Christian text that has contributed so many images to literature and popular culture – the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the Seven Seals, the Whore of Babylon, the Beast and the False Prophet, all of whom are defeated by the forces of good. The second part, Credo, is an extended chorus that has been performed several times as a concert work. The text is a translation of writings by Giordano Bruno, a 16th-century Jesuit priest who was also a philosopher and astronomer. Bruno’s ideas of spirituality, and the place of the world in the universe, were so disturbing to Catholic authorities that he was imprisoned and put to death in 1600.

Part of the difficulty in restaging Apocalypsis has been that the forces that Schafer specifies for performance are enormous, requiring a muster that evokes the original military meaning of avant-garde. Toronto conductor David Fallis, who has performed Schafer’s work in the past, will be leading the advance. Samoan choreographer Lemi Ponifasio and MAU, his ensemble, will be the central group involved in the staging. Canadian star performers Brent Carver, Tanya Tagaq, Denise Fujiwara and Nina Arsenault have solo roles. New Zealand opera singer Kawiti Waetford will join them, and performance art legend Laurie Anderson will have a video cameo as well.

Then there are Apocalypsis’ ensemble requirements. The list of performers constitutes a music festival in its own right. Groups from all over Ontario are participating – see the list of choirs at the end of the column, which does not even include the many instrumentalists involved. There will be close to 1,000 performers – dancers, soloists, choristers, conductors, brass, strings (including 12 string quartets!), winds and percussion – in the Sony Centre in three performances on June 26, 27 and 28, making Apocalypsis a Mahlerian endeavour indeed.

That the performance of such a large work has been made possible is a tribute both to the producers of Luminato and the commitment of Canadian ensembles to indigenous modern composition. Conductor Fallis speaks with enthusiasm about the conductors and choirs that he had never worked with, and whose drive and excellence he has come to admire. Considering that the last complete performance of Apocalypsis took place 35 years ago, for many this one may well be a once-in-a-lifetime experience – but hopefully not. It is exciting to witness many Ontario groups joining together to make arts events take place, so let’s hope this will be a model for future collaborations, especially with Canadian works.

For tickets and further information, see luminatofestival.com.

|

Choirs Involved with Apocalypsis: Bell’Arte Singers |

Benjamin Stein is a Toronto tenor and lutenist. He can be contacted at choralscene@thewholenote.com. Visit his website at benjaminstein.ca.