![]()

As a first-year undergraduate at Capilano University’s Jazz Studies program in 2005, I, like the rest of my cohort, was automatically enrolled in a mandatory jazz history course. It was a survey course, designed to teach us how to listen actively, to distinguish between Armstrong and Parker and Coltrane, and to develop a sense of the historical arc of jazz in the 20th century. Our very first listening example was Livery Stable Blues, by the Original Dixieland Jass Band.

As a first-year undergraduate at Capilano University’s Jazz Studies program in 2005, I, like the rest of my cohort, was automatically enrolled in a mandatory jazz history course. It was a survey course, designed to teach us how to listen actively, to distinguish between Armstrong and Parker and Coltrane, and to develop a sense of the historical arc of jazz in the 20th century. Our very first listening example was Livery Stable Blues, by the Original Dixieland Jass Band.

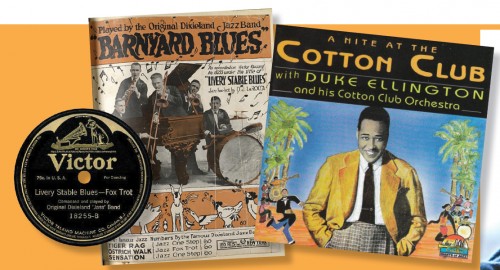

Something of a novelty song, its name derived from the horns’ imitation of animal sounds in stop-time sections, Livery Stable Blues has the distinction of being the very first jazz recording, released by New York’s Victor record label in 1917. It also holds a more dubious distinction: all five members of the ODJB, who billed themselves as the “creators of jazz,” were white.

To his credit, our instructor mentioned this unexpected fact, though we, as a class, did not investigate it further. There was much we could have considered: the circumstances behind the recording, the tricky concept of artistic ownership, the way in which Black American Music gets repackaged by white performers – from the ODJB to Elvis Presley to Justin Bieber – and profitably sold to white audiences. But we didn’t; instead, we moved on to the next song, and focused on learning to correctly identify excerpts for our upcoming exam.

This experience is indicative of what is still a defining characteristic of Canadian post-secondary jazz programs: namely, that they are primarily concerned with teaching students how to be competent professional performers, and that teaching students to engage with issues of race, gender and equity within their field is outside of a program’s purview. On the surface, there’s an undeniable logic to this: students come to learn performance skills, and that’s what programs deliver. One of the unintended consequences of this outlook, however, is an erasure of the lived experiences of jazz’s canonical figures, the vast majority of whom are Black.

Rather than being examined as real people, these musicians tend to become avatars of the music they made. The present-day significance of Duke Ellington’s famous 1920s residency at the Cotton Club, for example – a club which admitted a whites-only audience, was decorated in exotic jungle imagery, and was disdained by contemporary Black intellectuals like Langston Hughes – remains largely unexplored. Another unintended consequence of this colour-blind philosophy: faculty members and executive staff of Canadian jazz studies programs tend to be predominantly white men. Where greater diversity is visible, it tends to be in sessional faculty, hired on short contracts for relatively low pay.

The Call for Change

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, weeks-long Black Lives Matter protests, and loud calls for changes to be made to major arts organizations, a concerted effort has been made by students, alumni, and faculty to address the inequities of Canadian jazz programs. On June 24, a call to action addressed to the Humber College School of Media and Performing Arts was posted on social media by the Humber Jazz POC Alumni Collective – Kyla Charter, Meagan De Lima, Claire Doyle and Lydia Persaud. The letter contains both questions (such as “How are you supporting your Black students?” and “How is the department addressing systemic racism?”) and demands (“conduct and publicly publish an equity audit at the end of each school year” and “hire more Black professors and pay them well”). By June 29, a response was issued by both senior dean Guillermo Acosta and the Humber music faculty, with a commitment to effecting systemic change. This change includes working with the college’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Taskforce, “recruiting, retaining and advancing more faculty and staff from Indigenous, Black and other racialized communities,” and developing and allocating “more scholarships for Black and Indigenous students.”

#thisisartschool

Near the beginning of July, a group of University of Toronto Jazz Studies alumni formed under the auspices of the hashtag #thisisartschool, which emerged as a way for social media users to share marginalizing experiences at post-secondary arts programs. By July 17, members of this coalition – Modibo Keita, Jacqueline Teh, Laura Swankey, Laura Yiu, RJ Satchithananthan, Belinda Corpuz, Sammy Jackson, Alexa Belgrave, Joëlle Turner and Tara Kannangara – posted a call to action addressed to U of T’s Jazz Studies department, partly inspired by the earlier call to action addressed to Humber.

The U of T letter shares some similarities with the Humber letter, citing “the erasure of vital Black contributions to the arts” and “racism directed towards BIPOC students and faculty” as key issues. Unlike the Humber letter, however, which is primarily concerned with race, the U of T letter also highlights inequities related to gender and sexuality in jazz programs, including “discrimination directed towards LGBTQ+ students,” “the normalization of sexually inappropriate behaviour,” and the “lack of accountability for people who perpetrate these behaviours.”

Keita describes #thisisartschool as a coalition, and characterizes the process of making “decisions and sharing ideas” as “very organic.” Despite the “amount of people involved and the difference of opinions,” and the “highly delicate and emotionally charged” topics being discussed, he told me that the group has “rarely run into major issues.” For Keita, the “concept of jazz education in itself is inherently broken”; he doesn’t see the possibility of reform within the current academic model.

Keita describes #thisisartschool as a coalition, and characterizes the process of making “decisions and sharing ideas” as “very organic.” Despite the “amount of people involved and the difference of opinions,” and the “highly delicate and emotionally charged” topics being discussed, he told me that the group has “rarely run into major issues.” For Keita, the “concept of jazz education in itself is inherently broken”; he doesn’t see the possibility of reform within the current academic model.

In response to the issues that have been brought to the attention of the administration, the U of T Faculty of Music has formed a committee to address anti-racism, equity, diversity, and inclusion issues (AREDI). Kannangara – a sessional faculty member for the Jazz Studies program – is serving on the committee, along with fulltime faculty members, graduate and undergraduate students and other sessional faculty. The Jazz Area (U of T’s formal administrative title for its jazz program) is also forming its own AREDI, which, according to Jazz Area head Mike Murley, “will provide advice on how to make our program more inclusive, providing input on such matters as curriculum, workshops/masterclasses, recruitment of students, faculty and guest instructors, and overall student experience.”

The work of the committee is not without its challenges. It is easy, and not unfair, to point the finger upwards to university leadership when discussing equity issues. But, as Kannangara told me, “barriers are all around us, not just with our leadership.” Faculty and executives in post-secondary arts organizations tend to be liberal and invested in the idea of social progress; but systemic issues, no matter how severe, tend to be invisible, as if they’ve become “part of the furniture,” and introducing a new critical lens through which to see them can seem impossible.

Another major challenge, as Kannangara told me, is that so-called “diversity committees” tend to have “a lack of objectivity” amongst their membership. “Having a personal stake in policy outcomes,” as she put it, “is definitely a strength in some ways.” But, “it can be difficult to be efficient when you have your own personal grievances to air.” Though sharing these stories may be a necessary part of the process, she said, it’s important that they don’t hamper the committee’s capacity to “start making significant changes to the operations of the school.”

Another invisible issue: compensation for committee members. Committee members, Kannangara maintains, “should absolutely be paid. This work is extraordinarily labour intensive and to some committee members, retraumatizing. After a lot of conversation, I believe U of T is starting to take this seriously and I believe they are working on this point.”

In one sense, it’s easy to see the quarantine of 2020 – and the uncertainty attending the upcoming scholastic year – as yet another complicating factor in the fight for equity within post-secondary jazz programs. But, as Keita put it, some “people just started caring because they had time to [care] during the pandemic.” Though it comes at a significant cost, this year has afforded us all a rare opportunity to take time to pause, reflect and reform. What 2020 will mean for the future of jazz programs remains to be seen; hopefully, it will have been time well spent.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached at www.colinstory.com, on Instagram and on Twitter.