It’s Glee Club choir day at Toronto’s Baycrest Hospital. The grey-haired seniors, all diagnosed with dementia, are seated in a semi-circle in a room with colourful paintings and a big welcome sign. Most of them sit sedately. Some stare into space.

It’s Glee Club choir day at Toronto’s Baycrest Hospital. The grey-haired seniors, all diagnosed with dementia, are seated in a semi-circle in a room with colourful paintings and a big welcome sign. Most of them sit sedately. Some stare into space.

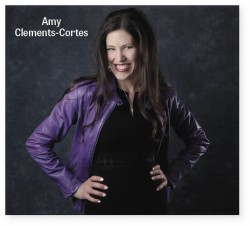

Dr. Amy Clements-Cortes, music therapist and assistant professor, University of Toronto, strides into the room and begins singing to the accompaniment of the keyboard.

Several clients join in and the group begins to awaken. Some tap their toes. Others clap their hands. A few bob their heads. Their eyes brighten as they focus on their conductor. Some don’t sing, but smile quietly. One man sits open-mouthed and lethargic for a while, but eventually grabs the hand of the staff person sitting next to him and pumps it up and down to the beat.

Clements-Cortes beams at the group. “You’re sounding nice,” she says.

Though she’s impressed with the quality of the singing, she’s also pleased by the ability of the music to temporarily revive her clients, many of whom suffer from Alzheimer’s.

Baycrest clients share the condition with about 376,000 Canadians, according to the Alzheimer Society of Canada. The disorder is projected to afflict 625,000 lives by 2032.

The disease is caused by abnormal protein clusters that build up in the brain and clog the connections between individual nerve cells, says Lee Bartel, professor of music at the University of Toronto. Over time the presence of these gummy blobs disrupt the circuits in the brain, barring structures from communicating.

Loss of memory is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Autobiographical memory, the recall of life events, is one type of recollection degraded by the disorder, says Ashley Vanstone, PhD candidate in clinical psychology at Queen’s. When patients forget pivotal moments in their lives, they lose pieces of themselves and their very sense of identity is shattered. “You see people slipping away from who they are.”

In a Toronto nursing home, the Villa Colombo, resident Maria Mirabelli sits motionless in her wheelchair. Her eyes are glassy, and she’s chewing on air.

The sentimental Italian song, Mama, comes over the speakers, and Mirabelli focuses, smiling softly and clapping. She starts mouthing the words to the song.

Her son John Mirabelli has seen this transformation before, but never fails to be astonished. “It’s incredible – she doesn’t even know my name,” he says.

The music is also inspiring flashbacks from her past, says activity aide Teresa Cribari. It returns her to the days when she cooked in her kitchen on Sundays while listening to the radio. “I think the music soothes her,” says her son. “It’s great to see her like that.”

Music has the uncanny ability to momentarily reanimate clients by activating their fraying memories, says Vanstone. One famous case involved EN, an Alzheimer patient who spoke in garbled sentences but still recognized familiar songs. Researchers concluded that memory for speech and for music resided in different locations in the brain, and the latter was relatively spared even in advanced dementia.

Scientists have since pointed out several mechanisms accounting for the doggedness of musical memory. To pull a tune out of storage you first need to make sense of it, says Vanstone. Compared to speech, music lends itself well to this task, as the grammar of music is internalized early in life. And, unlike in speech, the components of music are replicated – the melody is reinforced by accompanying chords, which are connected to regular rhythms. That means we’re not dependent on any one conveyor of musical meaning. “If your ability to perceive one mode is shaky, you’ve got lots of others.”

Scientists have since pointed out several mechanisms accounting for the doggedness of musical memory. To pull a tune out of storage you first need to make sense of it, says Vanstone. Compared to speech, music lends itself well to this task, as the grammar of music is internalized early in life. And, unlike in speech, the components of music are replicated – the melody is reinforced by accompanying chords, which are connected to regular rhythms. That means we’re not dependent on any one conveyor of musical meaning. “If your ability to perceive one mode is shaky, you’ve got lots of others.”

Not only can Alzheimer’s patients often recall melodies, they can also remember their lyrics long after they’ve forgotten where they live. The close association between the brain pathways for melody and lyrics accounts for this surprising feat, says Vanstone. “Melody and lyrics are like two parallel tracks joined by rungs – like a ladder. So the memory for melody can support the memory for lyrics.”

But music’s best stunt is its capacity to rekindle the milestones of our lives. These autobiographical memories include landmarks such as graduations and weddings, and are rich in sentiment. Music relies on these emotions to resurrect the recollections, says Vanstone. “Music is very good at conveying feelings – it builds up and lets go, giving a sense of tension and release,” he says. This ability to tap into our deepest passions helps us to draw out the experience that was laid down with the same fervent backdrop.

Music can also aid in recovering memories through its impact on our body’s physiology, says Ryerson PhD candidate Katlyn Peck. Music can stimulate areas of the brain responsible for releasing the chemical dopamine, which helps reconstruct memories. Retrieving a remembrance requires the brain to function at an optimal level of arousal – neither over-stimulated nor under-activated. Music can soothe anxious patients or activate depressed ones, creating the ideal environment for reminiscence.

While memory loss is hard enough for sufferers of Alzheimer’s, this problem can be compounded by depression. In the initial stages of the disease, clients are aware of their declining function. “They become frustrated with themselves when they recognize their problems,” says Clements-Cortes.

Fortunately, attending live concerts can partially reverse this complication, says Michael Thaut, professor of music at the University of Toronto. He led a study in which patients with Alzheimer’s attended nine monthly concerts along with their significant others. He noted striking changes in their moods over the course of the study. “They went from being frozen and inaccessible to smiling and singing along with the music.”

Back at Baycrest, one man with piercing emerald eyes and matching green pants becomes increasingly animated as the hour progresses. He acts out the songs with dramatic facial expressions and theatrical gestures. His baritone voice belts out Love Me Tender, as he gazes wistfully at Clements-Cortes and points his index finger right at her.

“I enjoy expressing myself,” he says. “Today I was expressing love – I can feel what the songs were saying.”

Music bolsters the mood many different ways, says Clements-Cortes. For starters, it provides an alternative method of communication when words have become compromised. As well, music stirs the production of endorphins. “These are the chemicals causing the pleasurable runner’s high,” she says. Rapid music also ratchets up arousal, ramping up breathing and heart rate.

Music also gives us a high akin to the glow of good sex or the lure of gambling. MRI scans have shown that listening to music engages the reward centre of the brain and triggers the discharge of the feel-good chemical, dopamine, says Thaut.

Tunes also counteract the immobility of depression. When people listen to music, the part of the brain responsible for movement becomes activated. Even if they continue sitting, their minds are in flight, says Thaut.

Anxiety is another common consequence of Alzheimer’s, says Thaut. As the disease progresses, patients no longer recognize their surroundings, their loved ones, or even their own memories. These deficits leave them feeling disoriented and can lead to agitation – yelling, resisting a bath, or even hitting loved ones.

Gina Scenna wanders up and down the hallways of Villa Colombo. She appears angry and confused. “She’s trying to look for something but she can’t find it,” says behaviour specialist Anna Abrantes.

Abrantes puts on her iPod filled with her favourite Italian songs. Scenna’s expression softens. She grabs Abrantes’ hands and starts dancing, bopping up and down in time to the music. When she tires, she sits down calmly, eyes closed, rapt in reverie.

Inspired by the movie Alive Inside, about the benefits of music on dementia, the Alzheimer Society of Toronto supplies free iPods, loaded with individualized music, to clients with dementia.

Our bodies are soothed by music, says Clements-Cortes. We produce oxytocin when we hear pleasant songs. This substance, known as the “the cuddle hormone,” is normally released in the presence of our lovers. “It gives us a feeling of contentment.” Listening to familiar tunes is also comforting and dials down our stress hormone, cortisol.

Music can be particularly reassuring to agitated Alzheimer’s patients, says Thaut. Its ability to stir memories back to life reduces clients’ disorientation. “If a person feels more anchored to themselves and to their environments, that makes them more secure.”

Music benefits the caregivers too, says Vanstone. “It’s tremendously rewarding to see their loved ones spark up a little bit.” As well, significant others don’t need to fear the side effects, including falls, which are an inevitable consequence of antipsychotics used to treat agitation.

The choir sings its final song, Shalom Aleichem (Hebrew for “Peace be upon you”). As the last harmonies soar to the ceiling, Clements-Cortes claps her hands. “Great job, excellent,” she says.

She is thrilled with the way music has temporarily turned back the clock on the singers’ lives. “Using music someone enjoys and has a connection to helps to revive their personality,” she says. “It’s like their old self is back for a little bit.”

The man in the green pants walks up to her at the end of the practice. He probably can’t articulate why he feels so stoked after an hour of singing. But he knows one thing. “I love you a bushel and a peck,” he tells his choir leader, referring to the lyrics of one of the golden oldies. Clements-Cortes is moved. “I’m honoured to work as a music therapist. I love seeing the benefits of music in their lives,” she says.

To obtain an iPod for your loved one, see alz.to/get-help/music-project.

Vivien Fellegi is a former family physician now working as a freelance medical journalist.