Lauren Spring, Art Gallery of Ontario educator, shares a painting on her Zoom screen. It is a tense scene. An old man, fuming, rises from his throne and points threateningly at a young woman draped in white fabric. She reaches towards several male figures to the left, but cannot resist craning her neck to face her accuser. The room is crowded and heavily shadowed, with light falling on a few furrowed brows. Some are staring at the old man, others at the young woman.

Lauren Spring, Art Gallery of Ontario educator, shares a painting on her Zoom screen. It is a tense scene. An old man, fuming, rises from his throne and points threateningly at a young woman draped in white fabric. She reaches towards several male figures to the left, but cannot resist craning her neck to face her accuser. The room is crowded and heavily shadowed, with light falling on a few furrowed brows. Some are staring at the old man, others at the young woman.

“What do you see going on here?” Spring asks the invisible audience of early elementary school students. “What grabs your attention, where does your eye go first?” The chat box explodes with observations. “There are lots of angry faces.” “There’s a royal character.” “A woman is being held captive.” “People are ashamed of the girl.”

Not bad: the subject is revealed to be a scene from King Lear, in which the aging ruler asks his three daughters how much they love him. While two are rewarded for showering their father with over-the-top praise, Cordelia, the most sincere, is disinherited for her modest response. Painted by the London-based Swiss artist Henry Fuseli, Lear Banishing Cordelia (1784-90) is, as Spring explains, “a good example of Romantic art, because it isn’t afraid of big emotions and big contrasts between light and dark.” Fuseli is famous for his melodramatic oil paintings, inspiring artists such as filmmaker Guillermo del Toro and, as we discover, co-presenter and violinist Shane Kim, from the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Over the next 30 minutes, students will compare storytelling techniques across painting, drama and music, and produce their own artwork in response to a live violin performance.

Every weekday, children across the country attend free AGO Virtual School Programs just like this one, held on May 10, while field trips remain off-limits. The museum’s art educators present three sessions daily, adjusted for age groups from kindergarten to third grade, fourth to eighth grade, and high school. (Today’s topic was “Art and Storytelling”; others include “Art and the Senses” and “Indigenous Art and Artists.”) The classes are wildly popular: so far, over 500,000 students have participated since last October, according to the museum’s learning department. This spring, guest artists from local and international organizations, including the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the National Ballet of Canada, are co-presenting works from the collection that inform their own practices.

Every weekday, children across the country attend free AGO Virtual School Programs just like this one, held on May 10, while field trips remain off-limits. The museum’s art educators present three sessions daily, adjusted for age groups from kindergarten to third grade, fourth to eighth grade, and high school. (Today’s topic was “Art and Storytelling”; others include “Art and the Senses” and “Indigenous Art and Artists.”) The classes are wildly popular: so far, over 500,000 students have participated since last October, according to the museum’s learning department. This spring, guest artists from local and international organizations, including the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the National Ballet of Canada, are co-presenting works from the collection that inform their own practices.

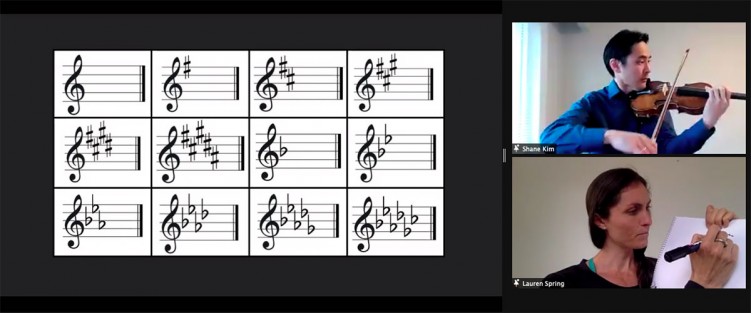

So, how might a classical musician approach visual art? In each of the sessions on May 10, violinist Kim describes how he was drawn to Lear Banishing Cordelia for its use of contrast. “There are these key parts of the painting that are clearly in the light, and everything else is very shadowy,” he says. In music, he tells us, contrast is just as important, and is used to highlight different musical ideas. Dynamics and tempo are among the many musical elements composers can vary, just as painters play around with spacing and colour. To demonstrate, he plays the Gavotte en Rondeau from Bach’s Partita for Violin No. 3 in E Major, in which repetitions of the main theme are interspersed with differing sections of increasing intricacy, building tension that is relieved each time that the theme reappears. He goes on to explain how key signatures form the “sound palette” available to composers, in the same way that a selection of paints does for painters, and how different orchestral instruments can be used to create a variety of characters in music, quoting from Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf as a literal example.

In the final minutes of each class, the table is turned, as students are asked to produce a sketch inspired by a piece of music. Kim plays the sweetly melancholic Après un rêve by Fauré, originally a vocal work, in which the singer reminisces about a lover who appeared to him in a flying dream. To convey this imagery, Kim shows how Fauré chose a minor key, with lots of flats, to express sadness. Rhythm is important too: the violin plays mostly triplets, while the accompanying piano sticks to standard eighth-note divisions, a choice that gives an impression of flight. As Kim explains, “the violin isn’t completely grounded with the piano, so it’s almost like I’m floating in the air.”

In their session, high school students, who would have likely studied Shakespeare and musical notation, enjoyed a detailed discussion of narrative techniques, Romanticism, and how artists reveal “complex emotional states” in painting and music. But if students are too young to know much about, say, King Lear, or a failed romance, are these works incomprehensible? After attending today’s sessions, I think not – great artists like Fuseli and Fauré pack their work with enough expressive detail to move any audience member. In response to Après un rêve, with no information beyond the title, students in the middle age group (fourth to eighth grade) created images very much in line with Fauré’s intended open-air setting and wistful mood. Among their descriptions of their sketches were: “Looking out of a window during a storm,” “Crying on a dock,” and the very poetic, “A man looking at the moon, wishing for a better life.”

Visual analysis and close listening are excellent skills to develop early. Many adult museum-goers (myself included) are guilty of looking past a work of art to the display label or guidebook, to memorize a few quick details – artist, title, date, provenance – before standing back and examining the work itself. Same goes for program notes at a concert. It is freeing to approach a work instead with fresh eyes or ears, evaluating our response to it – whatever the reputation or aim of the artist.

There are a few limits to the online format of the AGO sessions, of course, and 30 minutes often felt too short for a topic as broad as storytelling. It would have been helpful if the presenters had shown close-up slides of key painting details, such as facial expressions, which were difficult to see on a laptop screen. (It is also bad luck that the painting is not currently on display – I hope that decision will be reversed soon after the museum re-opens, so that students can examine it in person.) But it is unlikely that in-demand guest artists like Kim will be available to perform live repeatedly for AGO field trips once the city reopens, making this free program very special, and perhaps unique.

AGO Virtual School Programs continue weekdays until June 18. For the full schedule, visit: https://ago.ca/visit/group-visits/virtual-school-programs.

Jane Coombs is a writer based in Toronto. She recently graduated from Cambridge and the Courtauld Institute.