According to a fundamental theory of perspective in the visual arts (grossly oversimplified here), an image can be broken down into three distinct components: a background (the space furthest away from the viewer); the foreground (the area closest to the viewer’s eye) and the middleground, which defines the space between the foreground and background. Together, these areas combine to form the image’s composition. This idea of building perspective through layers of perception carries over well into other disciplines and, as we shall see, provides a useful platform for understanding an essential facet of classical music.

The concept of context affects every musical performance we encounter; and like the theory of composition outlined above, can be thought through in terms of background, middleground and foreground.

Some contexts are broader in scope and include those pieces of historical background information that are essential in understanding how an individual composer, style or work developed. In the case of Beethoven’s Symphony No.9, for example, it is useful to know before listening that Beethoven was deaf when he composed and conducted this piece, and that the choral finale is Beethoven’s musical representation of universal brotherhood based on the Ode to Joy theme. For a composer as dense and innovative as Gustav Mahler, whose symphonic tomes can be immense and overwhelming to first-time listeners, a basic knowledge of the German symphonic lineage (Haydn led to Mozart, led to Beethoven, led to Brahms and Wagner, led to Bruckner, led to Mahler) can help provide some perspective and shape perceptions of a specific work in an informed way.

Middleground information includes those anecdotes and facts that inform our modern perspectives in relation to music. That the Ninth Symphony was performed at the site of the Berlin Wall in 1989, soon after its toppling, is an important historical moment, as was the performance of Barber’s Adagio for Strings at the site of the fallen World Trade Center 12 years later. Much like the composition of visual images, the musical middleground can easily be overlooked and even eliminated altogether, and the drawing of our attention to it is often a noteworthy and revelatory experience. (Consider the isolated girl in the middleground of Rembrandt’s Night Watch – how illuminatory, once made apparent!)

Perhaps the most important of the three layers of perspective, foreground context most informs our immediate perception of a musical work, taking the music, its venue and its audience and creating a micro-environment unique to that specific concert. Factors such as location (Is the concert in a formal concert hall, in an outdoor amphitheatre, or a converted parking garage?) and the social atmosphere (a white-tie fundraiser or gala is a very different experience from a jeans-and-T-shirt casual concert) provide different ways of looking at and listening to the musical works contained therein. Imagine, for example, hearing the Ninth Symphony in three places: in a concert hall; on the radio while caught in traffic driving to work; and blaring from tinny speakers outside McDonalds, in an attempt to keep misbehaving youth at bay. The musical work is the same each time, the performers may even be the same each time, but the environment in which we hear a specific piece of music inherently informs our response to that artwork on a case-by-case basis.

By changing essential components of a concert presentation, the performing artists themselves can redefine and recreate the contextual setup for a musical work. Because the back- and middleground contexts are essentially uneditable, the majority of these presenter-based decisions correspond with our foreground perceptions, as we shall see in three concerts this month, each of which varies a different aspect of the classical music experiential composition.

Place

Nuit Blanche is an annual cultural tradition in Toronto in which the city is transformed by hundreds of artists and nearly 90 art projects. This year’s event features a fascinating installation at the Aga Khan Museum; according to the project synopsis, Arrivals and Encounters: Sama will present music and art from around the world, inviting listeners “to listen to the rhythms and stories of artists whose roots extend around the globe. Sacred spiritual music and dance, including whirling dervishes, staged in quiet spaces will evoke the more contemplative side of the city. The museum grounds will host an illuminated sound installation, offering visitors the chance to experience art while feeling the pulse of the arrivals and encounters that shape our city.”

While this sounds like a fine opportunity to step outside of one’s musical comfort zone and a remarkably obfuscating and inappropriate inclusion within an early music column, it is perhaps even more remarkable (and redemptive for your columnist) to find Vivaldi on the program of such an event. At 7:30pm on October 5, musicians from Tafelmusik bring the music of the Red Priest to the Aga Khan, kicking off their Nuit Blanche exhibition with a disorientingly orthodox bang. The contextual question is clear: how will the venue and environment (whirling dervishes and all) change the audience’s experience and perception of Vivaldi’s music? One could certainly expect that the effect and affect originally intended by Vivaldi will be modified by the extraordinarily varied surroundings, and exactly how this is accomplished will undoubtedly be a highlight of the month.

Johann Sebastian Bach and Joni Mitchell walk into a bar…

So continues Tafelmusik’s contextual subterfusion, this time with their Haus Musik: Café Counterculture concert at the Burdock Music Hall on October 10. Incorporating and juxtaposing music from the 18th and 20th centuries through a series of classical standards and new arrangements of popular hits, concertgoers can expect everything from, well, J.S. Bach to Joni Mitchell, tied together through the concept of the coffee house. In the words of Tafelmusik: “It’s 1730s Leipzig, Germany. J.S. Bach and his colleagues gather at Zimmerman’s coffee house for weekly concerts featuring the new music of the day. Fast forward to Toronto in the 1960s. Yorkville (now known as the ‘Mink Mile’) is a hub of subversion and anti-establishment activism. Undiscovered artists are making their breaks and international acts have come to sling it in underground dives and coffee houses. Legends of this counterculture scene pepper music collections across the world.”

An ingenious and creative programming idea, the inherently multi-genre concept of café counterculture provides an opportunity to combine music that does not at first appear to fit together at all, creating an opportunity to produce a concert experience greater than the sum of the parts. In this particular instance, the foreground context will be a constantly shifting, unexpected series of works that could give unsuspecting audience members a hint of temporal whiplash, but do so in favour of an innovative means of exposing fresh ears to the masterpieces of bygone eras.

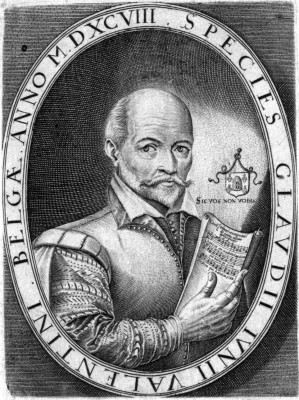

From extreme, genre-bending fluctuations within a single concert to more orthodox programming, the variation of context via musical means is a fluid and exploratory spectrum, as demonstrated by the Toronto Consort on October 25 and 26. In this instance, the fundamental organizational principle is the music of France, presented in a variety of forms and styles. Whether enjoyed in refined 16th-century courts or in today’s traditional music scene, the popular “voix de ville” songs and exquisite courtly music of Claude Le Jeune and his contemporaries or modern folk stylings, the appeal of French music has endured through the centuries. It is exactly these components, the countryside and court, combined with traditional fiddle and dance, that the Consort combines this month, a juxtaposition in triplicate that is sure to enthrall those in attendance.

With artistic direction by Katherine Hill, a well-known early music performer and director of music at St. Bartholomew’s Anglican Church, and guest fiddler and dancer Emilyn Stam, the musical quality will undoubtedly be top notch and well worth a listen.

After a relatively slow September, this month is full of remarkable and worthwhile early music concerts for all who enjoy the genre in all its forms. From conventional concerts in traditional venues to more exploratory programming in contemporary spaces, there is something for everyone in this issue of the WholeNote, and I encourage you to support as many of our talented artists as possible. Have questions as you develop your own contextual compositions? Email earlymusic@thewholenote.com for your October tutorial.

EARLY MUSIC QUICK PICKS

OCT 19, 2:30PM and OCT 20, 7:30 PM: University of Toronto Faculty of Music. Early Music Concerts: Handel’s Acis and Galatea. Heliconian Hall. One of Handel’s miniature dramatic works (referred to as a ‘little opera’ in a letter by the composer while it was being written), Acis and Galatea was the pinnacle of pastoral opera in England, Handel’s most popular dramatic work, and his only stage work never to have left the opera repertory. This is a fine opportunity to hear the University of Toronto’s rising stars, led by the superbly talented Larry Beckwith.

OCT 27, 2PM: Rezonance Baroque Ensemble. “Bach’s Extraordinary Oboe.” St. Barnabas Anglican Church. Dig deep into the Bach canon with his works for oboe, an instrument for which Bach was undoubtedly fond: not only does this instrument receive some of the most beautiful passages within the cantatas and passions, but Bach also composed four concerti, passed down in various forms and instrumentations and reconstructed for oboe and ensemble. Featuring U of T alum Ruth Denton on the double reed, this concert will surely be a delight.

OCT 31 TO NOV 9, various times: Opera Atelier. Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Whether intimately familiar with this opera or only aware of it from the death-premonition scene in Amadeus, this opera is a sublime opportunity for the operatic veteran and neophyte alike to experience Mozart’s masterwork through a historically informed lens. With a superstar cast and magnificent orchestra, you can’t go wrong with this classic.

Matthew Whitfield is a Toronto-based harpsichordist and organist.