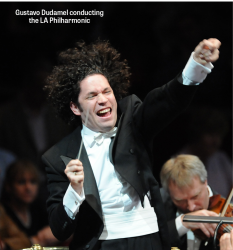

Gustavo Dudamel is widely considered the most exciting and gifted young conductor working today. His meteoric rise – he was appointed music director of the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in 1999 at the age of 18 and he’s now already in his fifth year as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic -- has been well documented. Winning the inaugural Bamberger Symphoniker Gustav Mahler competition at 23 was the first international signpost; being named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people five years later bumped up his media quotient. Two years later readers of Gramophone voted him Artist of the Year; two years after that Music America named him 2013 Musician of the Year.

Gustavo Dudamel is widely considered the most exciting and gifted young conductor working today. His meteoric rise – he was appointed music director of the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in 1999 at the age of 18 and he’s now already in his fifth year as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic -- has been well documented. Winning the inaugural Bamberger Symphoniker Gustav Mahler competition at 23 was the first international signpost; being named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people five years later bumped up his media quotient. Two years later readers of Gramophone voted him Artist of the Year; two years after that Music America named him 2013 Musician of the Year.

Toronto audiences will welcome him and the LA Philharmonic March 19 when he returns for the first time since 2009. Then, he conducted the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in support of his mentor José Antonio Abreu, at the time Abreu was awarded the Glenn Gould Prize for his monumental music education work in Venezuela. Having celebrated its 39th anniversary on February 12 – and yes, Dudamel was in Caracas that day, leading a youth orchestra from his hometown of Barquisimeto – El Sistema is thriving with more than 500,000 students.

Dudamel spoke to the Los Angeles Times about the experience of conducting the orchestra in which he grew up playing violin, the orchestra he had conducted at age 12.

“’All these young people,’ Dudamel enthused. ‘I felt like I was still one of them. [In Sistema] . . . We teach tolerance and respect. Whatever you think, you have to work together to play in an orchestra. Whatever your differences are, you have to solve problems to make harmony. The best example there is of what a community can be is the orchestra. . . Elsewhere in the world, music is a philanthropic enterprise. In Venezuela it is a right.”’

He’s fully committed to music as an engine for social change.

Abreu’s Glenn Gould Prize sparked David Visentin to launch Sistema Toronto in September 2011 with Abreu’s’s blessing. (You can read about it in The WholeNote’s March 2013 issue.) About 150-175 students of Sistema Toronto will not only be attending the LA Philharmonic concert but performing in the Roy Thomson Hall lobby for gala attendees in advance of the show. The Corporation of Roy Thomson and Massey Hall is bringing them to the concert free of charge as part of its Share The Music program.

Toronto is the fifth stop on a seven-city nine-concert L.A. Philharmonic North American tour, six concerts of which are comprised of John Corigliano’s Symphony No. 1 (1989) and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5. It’s a heavily romantic program, the two works composed about a century apart. Corigliano has written that his symphony “was generated by feelings of loss, anger and frustration” after the loss of many of his friends and colleagues to the AIDS epidemic affected him deeply. He decided to relate the first three movements of the symphony to three lifelong musician friends and recall still others in the third movement “in a quilt-like interweaving of motivic melodies.” He pointed out that Berlioz, Mahler and Shostakovich were also inspired by important events in their lives.

The current tour follows the LA Philharmonic’s recent Tchaikovsky Fest in which the orchestra split the six Tchaikovsky symphonies with Dudamel’s other ensemble, the Simón Bolívar Orchestra (it lost its “Youth” tag in 2011 as its members aged), so we should expect the players to have an even greater familiarity with this symphonic staple with its famous recurring Fate motif and iconic slow movement. (One can’t help wondering what Tchaikovsky’s fate would have been had he been born 100 years later.) Dudamel’s ability to reveal the soul of a piece of music will be put to the test. But watching the conductor rehearsing Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet without a score (!) on YouTube inspires great confidence and anticipation of a passionate and uninhibited performance.

Edwin Outwater and the KWSO: California-born Edwin Outwater, the music director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony since 2007, has also been celebrated for his work in music education and community outreach. In 2004 his education programs at the San Francisco Symphony were given the Leonard Bernstein Award for Excellence in Educational Programming. At the San Francisco Symphony, he conducted Family Concerts as well as Adventures in Music performances, heard by more than 25,000 students from San Francisco schools each year; and Concerts for Kids, which reached students throughout Northern California. In Florida, Outwater designed the Florida Philharmonic Family Series and its Music for Youth program, attended annually by more than 40,000 fifth-grade students in South Florida.

Edwin Outwater and the KWSO: California-born Edwin Outwater, the music director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony since 2007, has also been celebrated for his work in music education and community outreach. In 2004 his education programs at the San Francisco Symphony were given the Leonard Bernstein Award for Excellence in Educational Programming. At the San Francisco Symphony, he conducted Family Concerts as well as Adventures in Music performances, heard by more than 25,000 students from San Francisco schools each year; and Concerts for Kids, which reached students throughout Northern California. In Florida, Outwater designed the Florida Philharmonic Family Series and its Music for Youth program, attended annually by more than 40,000 fifth-grade students in South Florida.

In Kitchener-Waterloo, he redesigned the orchestra’s education series and initiated myriad community connections. He’s known for his Intersections program. Blogging about it last November he called it “a place for artists who didn’t fit into a particular musical category — people like violinist/fiddler Gilles Apap, composer/DJ Mason Bates, Western/Indian musician Suba Sankaran and others.”

He continued: “But it quickly became a home for people who wanted to try something with orchestra: saxophonists, scientists, chefs, yogis, videographers, you name it. It became a place where an orchestra can do anything, and by my estimation, one of the coolest, riskiest endeavors attempted by any orchestra in North America.

“From the beginning, people took notice. A lot of our shows were played at Koerner Hall in Toronto, thanks to the good faith and adventurous spirit of Mervon Mehta. I’ll never forget when our music/neuroscience show with Daniel Levitin, Beethoven and Your Brain, sold out there a week in advance... It confirmed my belief that orchestras don’t exist in a vacuum, but in the world of thought, emotion, and ideas.”

His innovative approach to programming is evident in the way he constructs and rationalizes a more traditional concert such as the one featuring Jon Kimura Parker on March 21 and 22. He’s subtitled the Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor “Brahms the Progressive” and Verklärte Nacht “Schoenberg the Romantic,” seemingly turning conventional wisdom upside down – until it sinks in that Schoenberg’s “Transfigured Night” is one of the most romantic pieces in the repertoire.

Two Recent Concerts: Benjamin Grosvenor’s Music Toronto recital was a revelation, more than justifying the acclaim that preceded his debut last month. The first half of his program consisted of Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann pieces written within 12 years of each other ending in 1839. The 21-year-old Englishman played with a sensitivity and finely calibrated tonal palette coupled with a technical prowess that was always at the service of his exceptional musicianship. Schubert’s Impromptu in G flat, Op. 90 No. 3 (D899) evoked memories of Dinu Lipatti with its warm sound. After intermission came three superbly spacious miniatures by Mompou, two Medtner “Tales,” the second of which, “March of the Knights” was a favourite of Horowitz, himself a favourite of Grosvenor. Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales shimmered but was not insubstantial while Liszt’s Valse de l’opéra Faust de Gounod showed off the pianist’s chops without sacrificing any part of the music’s well-entrenched musical lines.

Kent Nagano’s coherent, exciting performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra at Roy Thomson Hall not long ago has me looking forward to his forthcoming appearance with Tafelmusik next January when he will be conducting Beethoven’s insdispensable Symphony No. 5 and underrated Mass in C Major.

Two Parts of Triple Forte: When he hosted This Is My Music on CBC Radio 2, Ottawa-based pianist David Jalbert spoke about how he had been intimidated by Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations until hearing Murray Perahia’s version showed him that there are other ways to play the piece. On March 11 the Music Toronto audience will get a chance to hear how Jalbert’s interpretation of Bach’s seminal masterpiece has evolved since his CD of it was released to wide acclaim (including Christina Petrowska Quilico’s review in the May 2012 WholeNote) two years ago.

Coincidentally, on March 20 the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto is presenting the impressive cellist Yegor Dyachkov, Jalbert’s partner in the Triple Forte trio (violinist Jasper Wood is the third member), in a tantalizing program with pianist Jean Saulnier that includes the world premiere (and WMCT commission) of Atonement by Christos Hatzis.

Beethoven’s middle cello sonata as well as Britten and Shostakovich’s contributions to the repertoire complete the afternoon’s recital.

And More: The redoubtable Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society has six concerts on tap this month and two in the first week of April. Of particular interest: James Campbell performs Brahms’ second sonata for clarinet and piano (with Leopoldo Erice) on March 8 then joins the Penderecki String Quartet for the composer’s sublime Clarinet Quintet. Trio Voce includes Marina Hoover, founding cellist of the St. Lawrence String Quartet, violinist Jasmine Lin and pianist Patricia Tao. Their March 21 evening features trios by Haydn, Dvorák and Brahms.

On March 16, Mooredale Concerts presents Guillermo González performing his own edited version of Albéniz’s Iberia Suite. Judging by his 1998 Naxos recording, González clearly transmits the Spanish character of this keyboard masterpiece in an engaging rough-hewn manner compared to the more elegant style of his fellow Spaniard Alicia de Larrocha. (For sheer virtuosity, Marc-André Hamelin’s luminous, impressionistic version is unmatched, however.)

Angela Hewitt continues her recent foray into Beethoven’s universe (see this month’s DISCoveries) with her TSO appearance March 20 and 22 playing the composer’s Piano Concerto No. 5 “Emperor.” Guest conductor Hannu Lintu also leads the orchestra in Sibelius’ thrilling Symphony No 5.

Paul Ennis is managing editor of The WholeNote.