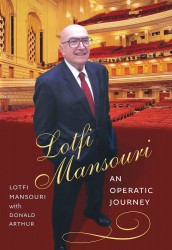

Lotfi Mansouri: An Operatic Journey

Lotfi Mansouri: An Operatic Journey

by Lotfi Mansouri with Donald Arthur

Northeastern University Press

344 pages, photos; $44.95

• While Lotfi Mansouri was general director of the Canadian Opera Company, he wrote a sunny memoir called An Operatic Life. Now, almost thirty years later he has followed up with this far more detailed, but decidedly bittersweet, chronicle of his life. It’s a candid and probing look at the world of opera. And it’s especially compelling because, right from his lonely, privileged early years in his native Tehran, Mansouri has led a thoroughly fascinating life.

Mansouri certainly left his mark on the COC, as he proudly points out, calling the chapter on his twelve years in Toronto “From Provincialism to World-Class.” Under his leadership, the COC Orchestra and the COC Ensemble were established, a splendid home for offices and rehearsal spaces was built, and the CBC began broadcasting COC performances on radio and television. But his most far-reaching legacy – he credits his wife Midge with the original idea – is the invention of Surtitles, which have revolutionized the way opera is presented throughout the world.

Mansouri set up a Canadian Composer’s Program, though it was cancelled by his successor, Brian Dickie. He produced R. Murray Schafer’s Patria 1 (misidentified as Patria II, quite a different opera altogether), and commissioned Harry Somers’ Mario and the Magician. So it’s not just discouraging, but downright perplexing to read what he has to say about his attempts while in Toronto to find a composer for A Streetcar Named Desire (André Previn’s score was a great success for him later in San Francisco). After Stephen Sondheim(!) turned it down, “I checked out Canadian composers, of course, but most of them were academic navel-gazers … My composer had to understand smoky jazz and genteel decay. With all respect, Toronto could never inspire that kind of music – Canadians are too hygienic.”

Though his time in Toronto was “exciting, joyous and highly collaborative,” his frustrations over trying to get a new opera house built here drove him to the San Francisco Opera in 1988. Although he had spent a good deal of his directing career there, he had no inkling of the far more insidious frustrations that awaited him. The earthquake that wreaked havoc on his early seasons was nothing compared to the betrayals that eventually forced him out.

The issues weren’t merely personal. It was his traditional approach to presenting opera, which for Mansouri meant “to read between the lines without neglecting to read the lines,” that was attacked by those who wanted to see a director’s personal stamp on a production. Mansouri, who started as a singer, felt his own work as a director was being written off as not just old-fashioned, but, even more disturbingly, as lightweight. So at the heart of this book lies a plea for staging operas by using the score as the starting point, not the director’s vision.

Mansouri is a born storyteller. Among his many delightful anecdotes, my favourite tells how the irascible conductor Otto Klemperer, who had been hideously rude to Mansouri, fell asleep with his head on Mansouri’s shoulder during a dress rehearsal. “No amount of training can prepare anyone for a situation like that.” At least he keeps laughing – and making us laugh – in this wonderful memoir.