Quick, how many Gounod fans have you encountered in your life? Before meeting pianist Steven Kettlewell, the man behind the Castle Frank House of Melody’s new concert offering, “Ga-Ga for Gounod” (April 7 at St. Andrew’s United on Bloor St. E.), my answer would have been scarcely any. Composer of very Catholic operas and of the overplayed Ave Maria? Not a lot to be excited about there. When the early listing for the Gounod song recital arrived in this magazine’s inbox, I found myself intrigued. Of course he would have composed songs, as most of his peers did, but what were they like – how much unlike his arias, how Catholic, how Romantic, how French? Most of French 19th-century song before Debussy and Ravel remains little performed, with one notable exception, Berlioz’s masterwork Les nuits d’été.

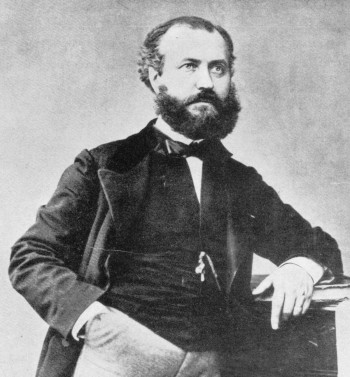

Charles Gounod (1818-1893) is certainly best known for his operas, says Kettlewell when we meet in his apartment in a charming mid-rise, a short walk up the hill from behind the Castle Frank subway station. Some of Gounod’s better-known arias will be in the program—two from Roméo et Juliette and three from Faust. The motley selection of Gounod songs in the program contain several in the English language, to poetry by Tennyson, Wordsworth and Shelley. Was he an ardent English poetry reader? “He lived in England for a period of time. During the war of 1870 between France and Prussia, Gounod moved his family to England. His wife returned after the Paris Commune was defeated, but Gounod ended up staying another four years. He met there a certain Georgina Weldon, an eccentric battleaxe of many causes… One of her pet causes became Gounod.”

Charles Gounod (1818-1893) is certainly best known for his operas, says Kettlewell when we meet in his apartment in a charming mid-rise, a short walk up the hill from behind the Castle Frank subway station. Some of Gounod’s better-known arias will be in the program—two from Roméo et Juliette and three from Faust. The motley selection of Gounod songs in the program contain several in the English language, to poetry by Tennyson, Wordsworth and Shelley. Was he an ardent English poetry reader? “He lived in England for a period of time. During the war of 1870 between France and Prussia, Gounod moved his family to England. His wife returned after the Paris Commune was defeated, but Gounod ended up staying another four years. He met there a certain Georgina Weldon, an eccentric battleaxe of many causes… One of her pet causes became Gounod.”

Gounod’s English-language songs sound very “English regional composer of the Victorian era,” says Kettlewell. “Even a bit like Arthur Sullivan. And some of the poetry is very sentimental.” One of the poems in the program is The Worker (1872), written by the then-in-demand lyricist Frederick Weatherly, also known for Danny Boy and Roses of Picardy. It could be taken for a social-realist song about the harsh conditions of a worker’s life were it not for the Catholic resolution, with angels arriving to take his soul to the higher plane of the afterlife for a well-deserved reward.

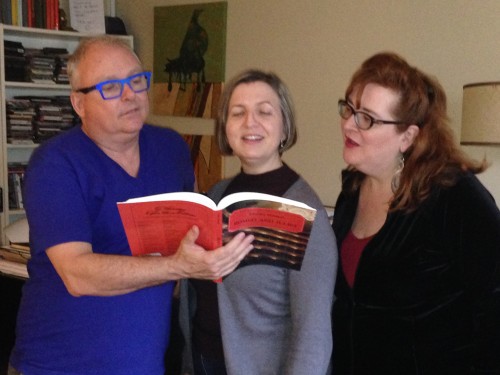

Gounod’s French songs, on the other hand, are very much salon songs, says Kettlewell. “He’s a lyrical composer who knows how to compose for the voice, and that comes across in songs as well.” Thematically, they involve “lovely, simple poetry, simple emotion. ‘I love you,’ or ‘It’s a beautiful spring day,’ or ‘A beautiful night’. Soprano Cara Adams is going to sing one called Boire à l’ombre, which has more meat to it than some of his other songs. Years ago I bought a collection of 15 duets by Gounod for soprano or mezzo and baritone, and here I’m including a selection.” Adams and two other sopranos, Patricia Haldane and Lorna Young, with mezzo Martha Spence and baritone Michael Fitzgerald, make up the soloist roster. Kettlewell mans the piano.

It was a heady operatic century for France, the 19th, and the program will show some of its range. We’ll hear some arias from Bizet’s Carmen, but also the more obscure Benjamin Godard and Fromental Halévy. And one song by Fanny Mendelssohn. What’s the connection there? “She met him while they were in Rome – where Gounod won the Prix de Rome. She wrote a letter to her brother in which she describes him as ‘charming.’ She extolled to him the virtues of modern German music at the time, and also Bach. Later, on his way back to France via Vienna, Gounod visited them in Weimar for a few days and got to know the brother Felix as well.”

On his return to Paris after the extended stay in Rome, Gounod seemed to be in no rush to become an opera composer. “What you’d normally do as a young composer is try to hook up with a librettist and start composing, maybe a short opera, in the hope that say the director of Opéra Lyrique would see it and give you a commission. He instead took a job as a church organist. He was that for a few years. He wrote masses and choral pieces and didn’t try hard to get invited to salons and meet librettists, schmooze, get to know people.” He also got a job writing music for schoolkids.

A lot of the operatic works of that time underwent rewrites and recycling, extensions and cuts, demanded by opera house directors, star singers or the state censor. “The second version of Gounod’s Faust, with recitatives instead of spoken dialogue, was much more successful than the first one,” says Kettlewell and hands me a book that’s been lying on his coffee table. “I’m reading this right now, Second Empire Opera: The Théàtre Lyrique Paris, 1851-1870 by T.J. Walsh, it’s hilarious. It’s about Théâtre Lyrique, the house that wasn’t subsidized by the government, unlike Opéra de Paris. [There are] a lot of composers in this book that we’ve never heard of, operas we’ve never heard of. The Lyrique would put on an opera and if it wasn’t very successful, they’d put a work on that was successful last year but rejig it for this year’s use. The stuff popular with the audience would push other works aside. They had to make money off opera.”

The works commissioned by the state-subsidized Opéra de Paris were always under the eye of the censor. Even Sapho was sent back for an edit because in one scene there was a hint of a sexual bargain between two minor characters. “All the while, the subscribers had the right to go back stage and flirt with the ballerinas. Viardot once said something to the effect that ‘what we were doing onstage was no worse than what was happening in the wings during the performance’.” The pestering of the ballerinas was part of the subscription package.

The censors also kept a close eye on anything that might cause political unrest. “They didn’t want people getting excited at the opera house and then running out to the streets and rioting … which was a French tradition.” Gounod’s own opera on Ivan the Terrible never saw light of day because there was never a good time to show regicide and assassination attempts onstage. While Gounod was writing it, Napoleon III was nearly assassinated on his way to the opera with his wife: somebody threw a bomb under their carriage. Gounod’s opera plot, coincidence would have it, also contained an assassination attempt. “People began saying to him, you’ll never get this on stage, start something else.” So he did. He relinquished the libretto to Bizet and moved on to other matters.

An example: the opera Cinq-Mars, which Gounod created for Opéra-Comique, and which was revived only in 2017 in a German opera house and recorded by Palazzetto Bru Zane as part of their lavishly designed French Romanticism series. (Kettlewell of course owns the CD.) When I tell him that Opéra-Comique is reviving Gounod’s second opera, La nonne sanglante, in June this year and that I have a ticket, since one of my favourite conductors is on the podium, the conversation veers into the phenomenon of nunsploitation (nun + exploitation), known to us from genre movies but already familiar to 19th-century operagoers. Rossini’s Le Comte Ory is still probably the best known of the type. “Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable also has some of that with the dance of the ghosts of nuns who rise from their tombs,” Kettlewell says.

As to the question of how Gounod fits in with the idea we have of French Romanticism: “I’d always offer some other names first in that context – certainly Berlioz – but with Gounod, there’s always a bit of restraint there, I think,” he says. He also mentions the then-star Meyerbeer as a more typical exponent. “What operas by Meyerbeer I’ve heard, I liked a lot. You sometimes wonder why some things fall out of fashion… and Meyerbeer has.” His Les Huguenots has seen some revival success in Belgium, France and Germany in the last few years. “Yes, and I just got a DVD of Margherita d’Anjou… and Robert le diable was done at the Covent Garden recently.”

Of all of Gounod, what would be his top five that everybody should hear? “Remember the Alfred Hitchcock Presents series? The opening credits music? That’s Gounod, the Funeral March of a Marionette, and he wrote it to poke fun at a British music critic.” Also on that list, the Jewel Song from Faust and Je veux vivre from Roméo et Juliette. “O ma lyre immortelle from Sapho is beautiful, as is the one from Cinq-Mars that we’re including in the program, Nuit resplendissante,” he says.

“And, of course, the Ave Maria.”

Ga-Ga for Gounod takes place inside the modernist concrete beauty that is St. Andrew’s United Church, 117 Bloor St. E., on April 7 at 7:30pm. Tickets $20 in advance (triciahaldane@gmail.com to arrange an e-transfer) or $25 at the door, cash only. There will be a salon party after, directions to the location to be given from the stage.

Lydia Perović is an arts journalist in Toronto. Send her your art-of-song news at artofsong@thewholenote.com.