Seminal Schoenberg: A Mini-Revival of the Second Viennese School

![]()

Late in 1974, CBC Radio, in collaboration with writer/host Glenn Gould (1932-1982) and with me as producer, presented Arnold Schoenberg: The Man Who Changed Music, ten one-hour-long broadcasts honouring the centennial of the birth of composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951).

Late in 1974, CBC Radio, in collaboration with writer/host Glenn Gould (1932-1982) and with me as producer, presented Arnold Schoenberg: The Man Who Changed Music, ten one-hour-long broadcasts honouring the centennial of the birth of composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951).

It was a comprehensive series of programs, and in the course of those ten episodes a great deal of Schoenberg’s music was heard, including the early Romantic works, the middle period, freely atonal pieces and the serial, 12-tone works of his late period. The inclusion of much of the Austrian/American composer’s piano music, as recorded by Gould himself, was a unique feature of the series. Gould’s script was written carefully and in a conversational style, for shared delivery between the CBC Radio staff announcer (or “sidekick,” as Gould at times called him), Ken Haslam (1930-2016) and Gould, the series host. The writing was clear, precise, with typical Gouldian exactitude. Every word was meant to count, even those words that appeared to express the personal opinions of Haslam, but which had clearly been placed in the script by Gould. And the point of all these words and music was to share as much of the Schoenberg legacy with CBC listeners as was possible within the allotted air time, and along the way, to demonstrate Gould’s devotion to it.

In the tenth and final chapter of that series of broadcasts, and at precisely the right moment for summative comments about the ten programs, Gould says, “Even now, 23 years after his death, it’s extraordinarily difficult to effect any really balanced judgment about Schoenberg’s contribution. Though it’s not particularly difficult to find an axe to grind and with which one can whack away with.” And despite Gould’s own personal admiration for Schoenberg’s music, he doubted that the composer would ever become, as he termed it, “a household word.”

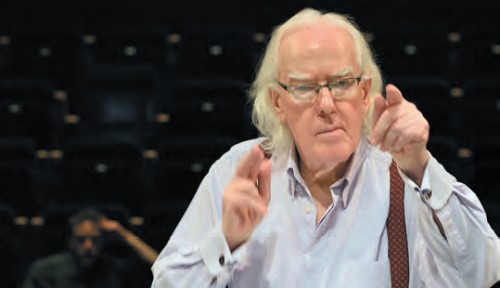

Notwithstanding this assessment of the prospects for a wider acceptance of the music of Schoenberg and his students and disciples – the so-called Second Viennese School – people like flutist/composer Robert Aitken, the founder and artistic director of Toronto’s New Music Concerts (NMC), value it as an essential foundation of today’s music. And in fact, within the first eight weeks of 2018, New Music Concerts’ programming will include Schoenberg’s Phantasy Op.47; his String Trio Op.45; the Chamber Symphony Op.9, in a quintet setting by Anton Webern (1883-1945); and Alban Berg’s (1885-1935) Chamber Concerto. A newly commissioned Chamber Concerto by Montreal composer Michael Oesterle (b. 1968), which uses the identical chamber orchestra as Berg’s concerto, will reflect the entire collection in the light of the present.

I asked Aitken what prompted him to create, in effect, a mini-revival of the Second Viennese School in New Music Concerts’ programming for 2018. He told me that the desire to include this repertoire is always a factor in his thinking, and that it has been so ever since he studied composition with John Weinzweig in the early 1960s. Weinzweig taught the 12-tone, or serial, technique of composing that Schoenberg had devised and introduced in 1921. Aitken told me that one of the aspects of Schoenberg’s music he admires is that, even given the frequent complexity of the counterpoint, the clarity of the music is never an issue. Aitken says that clarity and attention to every minute detail are also important values in his own compositions, musing that such attention to detail is a Virgo trait. (He and Schoenberg are both Virgos, as was Schoenberg’s student, John Cage (1912-1992).)

I asked Aitken what prompted him to create, in effect, a mini-revival of the Second Viennese School in New Music Concerts’ programming for 2018. He told me that the desire to include this repertoire is always a factor in his thinking, and that it has been so ever since he studied composition with John Weinzweig in the early 1960s. Weinzweig taught the 12-tone, or serial, technique of composing that Schoenberg had devised and introduced in 1921. Aitken told me that one of the aspects of Schoenberg’s music he admires is that, even given the frequent complexity of the counterpoint, the clarity of the music is never an issue. Aitken says that clarity and attention to every minute detail are also important values in his own compositions, musing that such attention to detail is a Virgo trait. (He and Schoenberg are both Virgos, as was Schoenberg’s student, John Cage (1912-1992).)

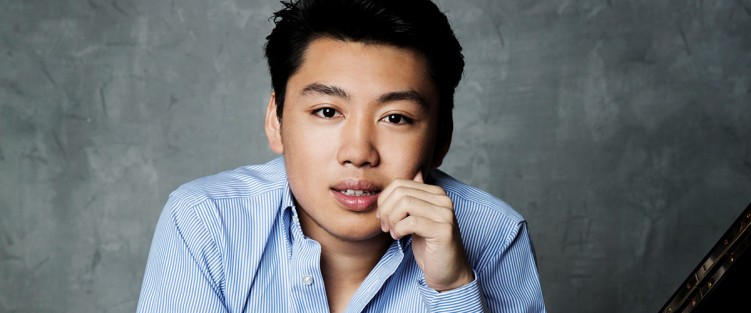

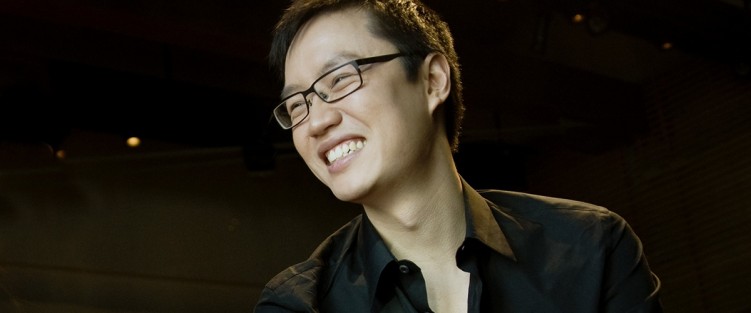

New Music Concerts’ three-concert Schoenbergian revival kicks off at the Betty Oliphant Theatre at 8pm on Sunday, January 14, with a program featuring the Chicago-based Duo Diorama, violinist MingHuan Xu and Winston Choi, piano, performing the Schoenberg Phantasy Op. 47, and as the soloists in the chamber concertos of Alban Berg and Michael Oesterle. In that tenth and final centennial broadcast in the CBC’s 1974 Gould/Schoenberg series, Gould said of the Phantasy, composed in 1949, and one of Schoenberg’s last completed works: “I still think it’s full of uneasy mixtures of Brahms and Wagner: you know, expressionistic violin lines, soaring, diving, equally expressionistic harmonics within a relatively four-squarish sentence structure.” Gould himself recorded the Phantasy with violinist Israel Baker in 1964 for Columbia Records.

The idea to commission the Chamber Concerto by Oesterle sprang from the shared enthusiasm by Aitken, Oesterle and Daniel Cooper, an enthusiastic NMC supporter, for the Berg Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 winds (1923-1925). Oesterle’s concerto has the same instrumental forces as the Berg, and it will receive its world premiere on the January 14 concert. The Berg Chamber Concerto will complete the program. Aitken will conduct the NMC ensemble, with Duo Diorama as soloists.

The idea to commission the Chamber Concerto by Oesterle sprang from the shared enthusiasm by Aitken, Oesterle and Daniel Cooper, an enthusiastic NMC supporter, for the Berg Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 winds (1923-1925). Oesterle’s concerto has the same instrumental forces as the Berg, and it will receive its world premiere on the January 14 concert. The Berg Chamber Concerto will complete the program. Aitken will conduct the NMC ensemble, with Duo Diorama as soloists.

Three weeks later, on February 4, at Gallery 345, NMC will present a 1923 Anton Webern arrangement of Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1 Op. 9 (1906). The Calgary-based Land’s End Ensemble will be joined by Aitken on flute and clarinetist James Campbell for this quintet version of one of Schoenberg’s more frequently arranged works. Schoenberg himself arranged the piece twice, for both smaller and larger forces. Berg made an arrangement for two pianos, and Webern’s arrangement itself exists in two versions. Land’s End Ensemble will also perform trios by Canadians Sean Clarke (b. 1983), Hope Lee (b. 1953) and Matthew Ricketts (b. 1986).

Finally, three weeks later on February 25, at 8pm at Gallery 345, NMC will present another late work by Schoenberg: his String Trio Op. 45 (1946), in a performance by Trio Arkel, along with a program of trios by Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933), Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952) and James Rolfe (b. 1961). The concert will be preceded at 6:30pm by a screening of the Larry Weinstein film, My War Years: Arnold Schoenberg.

Perhaps by the end of this sequence of three concerts, it will be revealed that any doubts about the value of Schoenberg’s contribution have, by now, diminished or even vanished altogether – and that, if not yet in Gould’s phrase “a household word,” Schoenberg is at very least a welcome and engaging house guest.

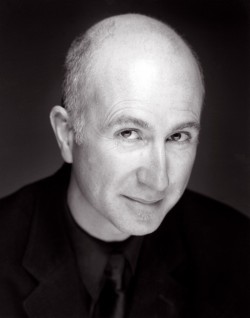

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.