Comings & Goings: Final Finales

“How come I never heard of these guys before?” is on balance a good thing to overhear from a departing concertgoer, if you’re the artistic director of a musical ensemble watching an audience file away after the final performance of your season. For one thing it means there was at least one new person in your audience that night. For another it means that, all things being equal, the individual in question is likely to be back.

“How come I never heard of these guys before?” is on balance a good thing to overhear from a departing concertgoer, if you’re the artistic director of a musical ensemble watching an audience file away after the final performance of your season. For one thing it means there was at least one new person in your audience that night. For another it means that, all things being equal, the individual in question is likely to be back.

When the performance in question is not just the final one of your season but the final one of your final season, though, it’s likely that the pleasure you take from the remark will be tinged with at least some regret.

Two upcoming performances this May both fit the “final finale” description, albeit in different ways. For Larry Beckwith’s Toronto Masque Theatre, “The Last Chaconne” on May 12 at the Jane Mallett Theatre will be the last performance before the company disbands. While for Toronto Consort, their May 25, 26 and 27 concert performances of Monteverdi’s signature opera Orfeo will signal the final appearances of David Fallis as their artistic director after almost

28 years in the role.

Lucky for us, Fallis’ and Beckwith’s respective decisions, to step aside and to disband, sparked opportunities for The WholeNote to sit with each of them for lengthy and wide-ranging conversations, which we will bring your way in more extended form once their May “last hurrahs” have been hurrayed.

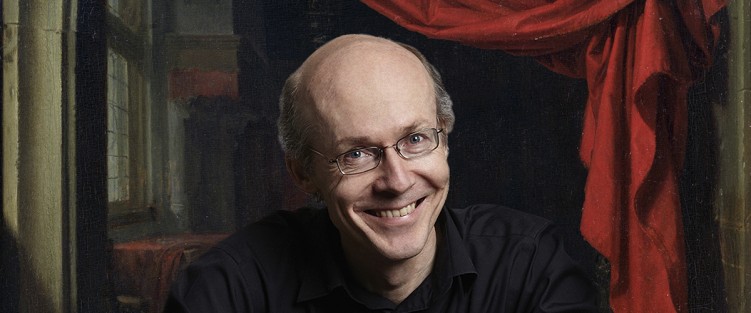

TORONTO CONSORT | The Beat Goes On

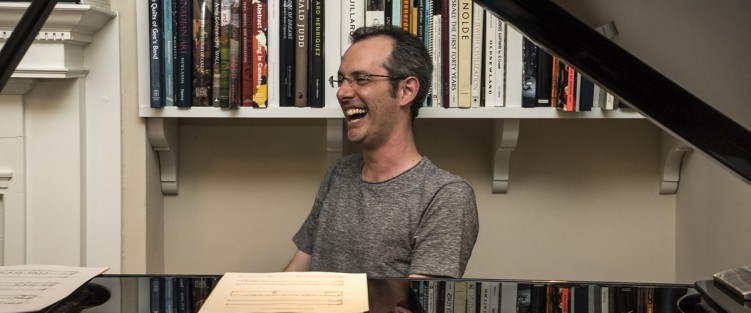

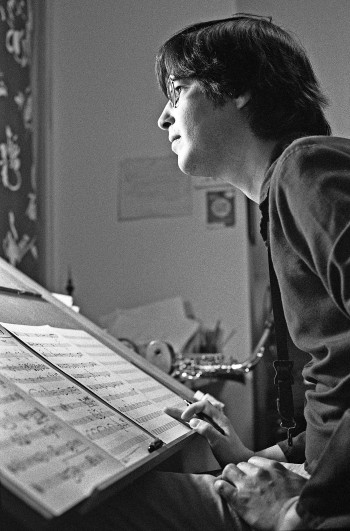

David Fallis didn’t start out as Toronto Consort’s artistic director. As a matter of fact, in 1979 when he joined, they didn’t have one; Fallis, a self-described “novice, who didn’t know all that much about the music” came aboard as part of a collective that included Garry Crighton, David Klausner and Alison Mackay. “One of them would just shoot us programs, and they’d do all the research, run the rehearsals and it worked well for 12 or 13 years,” he recalls.

Things evolve and change, though, and when the need arose for a steady curatorial hand at the helm, the role fell to Fallis.

Fast forward 27 years to the beginning of this past season, and Fallis went to the group saying he’d like to make this his last year as director and what should they do? “Full circle,” was the agreed answer: nine people who have worked together “in consort” for at least ten years, and in many cases longer, don’t necessarily need an artistic director.

Paradoxically, it’s because Toronto Consort is what is technically known as a “broken consort” that not much needs to be done to fix it! Broken, in consort terminology, means made up of instruments from a range of different families and types, as distinct from a “whole” consort, such as a family of viols. Because of that, the members of Toronto Consort are already strong individuals with different ideas, used to bouncing musical ideas off each other, figuring things out and, as necessary, taking turns at being the lead.

The coming year reflects this spirit of artistic collectivity: of the five concerts announced for the 2018/19 season, one will feature a guest ensemble, two will be curated by members of the ensemble who have previously curated events (Katherine Hill and Alison Melville); one will be co-curated by Fallis and Hill, and the tried and true Consort favourite, Praetorius Christmas Vespers, will be Fallis’ to direct.

That being said he’s not trying to pretend that there isn’t a special feeling about the upcoming show. Partly because of the place it played in the history of his time as artistic director, partly because of some favourite people he gets to include as guests – tenors Charles Daniels, Kevin Skelton and Cory Knight, and with Jeanne Lamon playing violin.

“As the last act – me officially as artistic director – you couldn’t do any better than a piece about the power of music, a man who is such a beautiful singer and musician that he can charm even the powers of hell” Fallis says.

Hail and Farewell | Toronto Masque Theatre

As even his closest collaborators over the past 15 years (company manager Vivian Moens and artistic associate Derek Boyes) would agree, without Larry Beckwith Toronto Masque Theatre would not have come into existence in the first place, or survived this long. He’s always carried it on his shoulders. And it was hard for even his closest collaborators over the years to envision carrying on. It was one of those “What am I going to do with my life calendar things?” – turning 40 – that led him to start the company. At 55 it just feels like the right time to stop: “not walking away, not fading away, just another chapter.”

Once the decision was made, last summer, TMT decided on a course of full disclosure that this season would be the last. “Hopefully to make this last season celebratory rather than funereal,” as Beckwith put it in one of our chats. And a signature season it has been, reflecting the full range of presentational styles, from intimate salon to large-cast spectacle, and of musical eras from early to contemporary to commissioned works that have become TMT’s trademark.

“The Last Chaconne” promises to be a fitting climax to it all, with a cast of collaborators that would be astonishing, if they were being roped in randomly for a special occasion, but in this case simply reflect TMT’s relationship-building musical history.

“The Last Chaconne” promises to be a fitting climax to it all, with a cast of collaborators that would be astonishing, if they were being roped in randomly for a special occasion, but in this case simply reflect TMT’s relationship-building musical history.

There will doubtless be a moist eye or two, a twinge of regret as they celebrate what they’ve achieved in the context of their collective passion for beautiful words, music and dance: excerpts from Acis and Galatea, The Fairy Queen, The Lesson of Da Ji, The Mummers’ Masque, Orpheus and Eurydice, a new commission from bassist Andrew Downing, and some beautiful dances featuring Marie Nathalie Lacoursière and Stéphanie Brochard … and more.

“The phrase ‘the means of grace’ has always stuck in my mind” Beckwith reflects. “In fact at one time it might have been the name for Toronto Masque Theatre, but someone, probably Vivian, thankfully, talked me out of it. In one sense of the word, grace is what Baroque dance is all about, but the phrase actually comes from a general prayer of thanksgiving in the Anglican book of common prayer.” He quotes from memory. “‘Being unfeignedly thankful for the blessings of this life, for the means of grace and the hope of glory, we show forth our praise not only with our lips but in our lives.’ Music has always been that for me.”

Simple questions sometimes lead to interesting answers:

“How did you know it was time? Do you even know how to relax? What will you miss and not miss?” And (of course) “So what will you be doing next?”

To the last of these, both Fallis and Beckwith respond with some variation of the response “All will be revealed in the fullness of time.” Clearly putting their feet up is not high on their respective lists of priorities.

Meanwhile, if you “haven’t heard of these guys before,” now’s your chance! Every finale is the start of something new.

FINAL FINALES:

Toronto Masque Theatre presents “The Last Chaconne: A Celebration” May 12, 8pm at the Jane Mallett Theatre. On the stage where it all began, a star-studded array of singers, actors, dancers and instrumentalists comes together for a farewell celebration at the end of their final season.

In David Fallis’ last concert as artistic director, Toronto Consort presents Monteverdi’s Orfeo, May 25 and 26 8pm, May 27 3:30pm in Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre. The world’s first great opera, and one of the most moving love stories of all time, starring English tenor Charles Daniels in the title role, many returning Toronto Consort favourites, and the Montreal-based early brass ensemble La Rose des Vents.