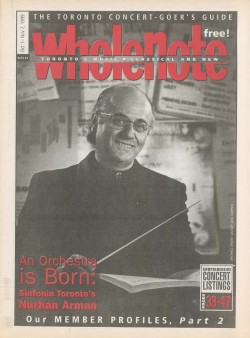

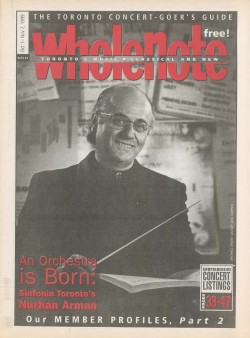

Just over 19 years ago, The WholeNote’s Allan Pulker interviewed conductor Nurhan Arman about the impending launch of chamber orchestra Sinfonia Toronto – an event that Arman described at the time as “the fulfillment of a dream.” Now, as Sinfonia Toronto’s 20th-anniversary season begins, we revisited with Arman to chat about a two-decade journey which has seen Sinfonia Toronto’s world expand from the GTA across Ontario and the globe, culminating in a historic South American tour in April 2018.

Just over 19 years ago, The WholeNote’s Allan Pulker interviewed conductor Nurhan Arman about the impending launch of chamber orchestra Sinfonia Toronto – an event that Arman described at the time as “the fulfillment of a dream.” Now, as Sinfonia Toronto’s 20th-anniversary season begins, we revisited with Arman to chat about a two-decade journey which has seen Sinfonia Toronto’s world expand from the GTA across Ontario and the globe, culminating in a historic South American tour in April 2018.

WN: Congratulations on your 20th anniversary. It’s quite an accomplishment.

WN: Congratulations on your 20th anniversary. It’s quite an accomplishment.

NA: Thank you, Paul. We are very proud of our accomplishments to date with Sinfonia Toronto. Our goal was to create a chamber orchestra with a specific repertoire that was missing in Toronto. Toronto had Baroque ensembles, symphony orchestras, opera and chamber music, but it was missing an ensemble that could play the string orchestra repertoire by 19th- and 20th-century composers as well as contemporary music. We achieved this goal as we have been performing this repertoire for Torontonians. Many remarkable compositions received their première performances in Toronto by Sinfonia Toronto. Just to name a few, I can mention major works by Kapralova, Vasks, Górecki, Mirzoyan, Hindson, McLean, and of course world premières of works by Canadian composers like Burge, Chan Ka Nin, Mozetich, Schmidt and many others.

And we have taken this repertoire to many schools, community centres, retirement homes. My most cherished memory of an outreach performance is from our concert at SickKids (The Hospital for Sick Children).

Every season we have performed in other Ontario cities. We have played from Sarnia to Sault Ste-Marie and from Welland to Brockville. We have proudly carried the name of our city and our beautiful repertoire abroad in tours to Germany, Spain, USA, Argentina, Peru and Uruguay.

And looking ahead?

As music director my goal for the future is to keep building the orchestra, enriching the repertoire and making the orchestra even better known in Canada and abroad.

Nineteen years ago, you told Allan [Pulker] how much you like the repertoire for string orchestra, calling it “pure music, like a string quartet except bigger and with a double bass.” I attended your concert last April in the Glenn Gould Studio, featuring Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 “Emperor” with Stewart Goodyear as soloist. I can attest to the orchestra’s vigour. The piano was much more exposed in the chamber version and there was textural depth and beauty to Goodyear’s playing.

Thank you for your kind words! Yes. There is an amazing amount of shading in the format. The dynamic range is incredible. It is truly a new way for audiences to appreciate familiar works.

So, what we can look forward to in your October 20 concert at the Toronto Centre for the Arts. How will you approach Mozart’s Horn Concerto No.4? Will it be performed on the trumpet?

On our season-opening concert on October 20, Mozart’s Horn Concerto No.4 will be performed by the incredible Sergei Nakariakov. Sergei plays this work beautifully on flügelhorn, an instrument that looks like a trumpet but is larger, with a wider bore. It works well for the horn concerti. As well, Sergei uses it for cello concerti that he plays! He also plays violin works on regular trumpet; he is amazing!

In terms of the other works on the program, the Shostakovich Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Orchestra is delightfully witty. What will the version for strings unearth? And what can we expect from Beethoven’s iconic Kreutzer Sonata?

The Shostakovich was written for a string orchestra, so we’ll play it in its original version. For Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, I started with a string quintet version that was made early in the 19th century, possibly by Beethoven’s student, friend and secretary, Ferdinand Ries. I have added a double bass part and made certain changes to the arrangement so that it works better for a string orchestra. Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata is one of the greatest works of the repertoire. As is the case with all masterpieces, the magical message comes across if it is performed well, whether it is played by a quintet, octet or just two musicians. I have been working on this score since May and I am sure my colleagues in Sinfonia Toronto will give their best efforts to perform this magnificent work in this version.

Are there other of your own arrangements in this concert?

Mozart’s 4th Horn Concerto is also my own arrangement.

Can you point to any other works in the upcoming season which you think will particularly benefit from the string orchestra format?

Many chamber music compositions like trios, quartets, quintets, sextets are enriched when they are arranged for a string orchestra. Great chamber works’ architecture and emotional depth make them good candidates for performance on a larger scale. The rich sonorities of a virtuoso string orchestra bring out the symphonic proportions of those compositions. And some works originally composed for larger instrumentation also sound new and wonderful when played with the great range of tones and textures that can be created by a highly skilled string orchestra.

Any particular examples?

Consider our November 16 concert which includes Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. We will play the North American premiere of a transcription by the French composer Louis Sauter. On the same concert we’ll play Bruckner’s Adagio from his String Quintet. In Rachmaninoff the transcription reduces the work to its basic elements; Rachmaninoff’s dialogue and thematic ideas are now taken into a more intimate setting. Performing this gorgeous work with an ideal collaborative pianist like Anne Louise-Turgeon will be an exciting new experience for the audience. In Bruckner’s Adagio we will stretch its dimensions. This work has already been transcribed for string orchestra several times, and has been recorded by many string orchestras.

It seems that transcription is vital for an ensemble of this type.

Transcriptions were very common practice until the mid-20th century when suddenly everyone became purists. All the major composers before then often transcribed their works for other combinations. Beethoven’s violin concerto was considered the “concerto of all concertos,” yet Beethoven himself made a version as a piano concerto! Fortunately times have changed again. I am proud of the many transcriptions that I have made and performed with Sinfonia Toronto. Many of them have also been played by other orchestras around the world, 24 orchestras in ten countries, at last count.

Almost 20 years ago you mentioned to Allan Pulker that Canadian programming was a goal. Can you give us an idea of the number of Canadian compositions Sinfonia Toronto has played over the years?

We have worked very energetically to serve and grow Canadian music. Considering the size of our season and the fact that we don’t specialize in contemporary music, our record is impressive. To date we have given 19 world premières of works by Ontario composers, as well as one by a Quebec composer, along with 11 Ontario or Toronto premières of works by Canadian composers; and we have performed 30 other works by Canadian composers, many more than once, including nine by Ontario composers and 13 by female composers.

During our international tours, we also featured Canadian composers at every performance. We played Sir Ernest MacMillan in Germany, in Spain Ontario composer Kevork Andonian, and in South America works by Chan Ka Nin, Alexander Levkovich and Marjan Mozetich.

How many works have you commissioned?

By Canadian composers: Kevork Andonian, John Burge, Scott Good, Chan Ka Nin, Christos Hatzis, Marjan Mozetich, Norbert Palej, Ronald Royer, Heather Schmidt, Petros Shoujounian and Rob Teehan. In addition, as music director with my other Canadian orchestras I have commissioned and premièred another 20 works.

I have also conducted several world premières abroad commissioned by orchestras that I guest conducted. I have premièred new works in Italy, Germany, Poland, the US and Armenia.

You were born to Armenian parents in Istanbul, where you gave your first violin recital at 13. How old were you when you started playing?

I started violin at age nine.

Please describe the musical atmosphere in your home growing up?

My mother was a concert violinist, but she gave up her solo career when I was born. When she began teaching me she resumed playing herself, but limited her performances to chamber music. My father had a good voice and was a choir member at Casa d’Italia.

Besides lessons with my mother and then other wonderful teachers, the greatest influence in my development was attending concerts by the Istanbul Symphony Orchestra and many recitals and chamber music concerts. In addition, I loved going to live theatre performances, movies and reading great literature. In a typical week I attended at least four or five events and sometimes two a day... I admit, I don’t sleep much in general!

This is one thing sorely missing in today’s music education – both students and parents are so busy with everyday life they can’t find time to attend concerts. To me this is a must, but how to implement it is the big question. Internet and social media also are time-consuming, but at least one plus for today’s music students is the convenience of being able to watch and hear great classical music with just a few clicks.

Did you have any musical idols in your youth?

Of course! Violinist David Oistrakh.

And when did your passion for conducting take root?

I began conducting as a side activity. Back in the 70s, I had an active career as concertmaster, soloist and chamber musician. In 1980, I was the concertmaster of the Florida Chamber Orchestra, based in South Florida. They sponsored the Florida Youth Symphony, an excellent orchestra, with membership from throughout the state. When their conductor departed in mid-contract, I was asked to take over. The management had seen me doing string sectionals and must have liked what they saw. After two seasons with the FYS, in 1982 I came to join my parents in Canada when they immigrated to Montreal. I thought I should look for a concertmaster position but the first opening within easy enough travel to be with them happened to be the music directorship of the North Bay Symphony. I auditioned and was offered a contract. Shortly after that I began guest conducting in Europe, and the more I conducted the more I fell in love with it.

What led to the birth of Sinfonia Toronto?

What led to the birth of Sinfonia Toronto?

In 1998 I moved to Toronto. At the time I was guest conducting five weeks or more in Europe every year and serving as music director of Symphony New Brunswick. The Chamber Players of Toronto had folded not long before, and colleagues and friends who love this repertoire formed a board to support my try at building a new group to fill the gap. We began with a six-concert subscription season in 1999-2000, and were able to move to seven the very next season. In 2002 I left Symphony New Brunswick to give all my attention to Sinfonia Toronto plus continuing guest conducting.

Have you discerned any changes in your audience over the years?

Definitely yes and happily so. When I first started doing some new compositions with Sinfonia Toronto there were a few subscribers who barely tolerated them. There were also a few presenters in other cities who were initially suspicious of unknown works and composers. It’s been truly rewarding to see how our audiences have come to trust our programming over the years. I see my role as music director not only as an orchestra builder but just as importantly in developing the audience and pushing the boundaries. Artistic organizations must lead their communities, not only produce what is safe and sells most easily.

What do you find most rewarding and most challenging in your professional life?

Performers love to experience the magical moments of complete communication and unity among themselves and with their listeners. I am always happy when we can achieve that a few times per concert.

I have conducted more than 90 orchestras around the world. It is always challenging but also very intriguing and exciting to meet a new orchestra and from the first moment of the rehearsal start developing this very special relationship.

Sinfonia Toronto’s first concert of their 20th-anniversary season takes place at the Toronto Centre for the Arts on October 20 at 8pm.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.

The way Linda Litwack tells this chapter of the Denise Williams story, she and Williams (who have known each other since about 1990, when Williams joined the Toronto Jewish Folk Choir as their soprano support singer/soloist) bumped into each other at the premiere, in October 2015, of David Warrack’s ambitious oratorio Abraham at Metropolitan United Church. (Litwack was the publicist.)

The way Linda Litwack tells this chapter of the Denise Williams story, she and Williams (who have known each other since about 1990, when Williams joined the Toronto Jewish Folk Choir as their soprano support singer/soloist) bumped into each other at the premiere, in October 2015, of David Warrack’s ambitious oratorio Abraham at Metropolitan United Church. (Litwack was the publicist.)