MUSIC & THE MOVIES: The Toronto Jewish Film Festival 2013

Please click on photos for larger images.

After “The Three Lennys” in 2011, its 19-event exhaustive examination of Lenny Bruce, Leonard Bernstein and Leonard Cohen, the Toronto Jewish Film Festival knew what it would do for an encore: TJFF’s sidebar series in 2012 was “The Sound of Movies: Masters of the Film Score.” With special guests, composers David Shire and Mychael Danna, leading the way, Toronto audiences were treated to a celebration of the Jewish gene’s musical genius.

For this year’s edition of the TJFF (tjff.com), which began on April 12, there’s no such overt attention being paid to the role of music in Jewish life, but there are a number of films that create an identity through music.

Pierre-Henry Salfati’s Gainsbourg by Gainsbourg: An Intimate Self-Portrait tells the riveting story of the iconic French musician in his own words, no mean feat since he died in 1991. Yet the conceit works brilliantly as a way into the mind of this man who would hear people say “God he’s ugly,” when he was onstage. He calls his face “ravaged” and says “I was misogyny incarnate,” but he romped with Anna Karina, had a child (Charlotte Gainsbourg) with Jane Birkin and wrote two of his most famous songs – “Je t’aime . . . moi non plus” and “Bonnie and Clyde” – for Brigitte Bardot.

Born Lucien Ginzburg, he became Serge out of nostalgia for Russia (“I am Slav in my soul”), a country his parents left after the revolution. Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue was “his first revelation,” but he couldn’t play it the way his father could. And his father was a harsh critic. Still, once his father died, he felt close to him through classical music.

Art Tatum, Rachmaninoff, Berg and Chopin moved him and he turned part of Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 into a pop song.

The film begins with a live concert near the end of his life (he died a month short of his 63rd birthday in March 1991), a veritable love-in thanks to his fans. Many of his revelations are accompanied by his own collection of videos, with movie pals Jean Gabin and Michel Simon or his daughter playing the piano under his tutelage. He drops personal and professional nuggets along the way. He was haunted by the Occupation when he was forced to wear a star and carry an axe into the woods for protection. He was an architecture student playing piano in a bar when he met Boris Vian (a major influence). Jacques Brel told him he’d only get ahead once he realized he was a crooner. Needless to say, that’s what happened.

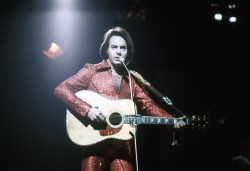

Neil Diamond was only three years younger than Gainsbourg; his more prosaic route to success is examined in Samantha Peters’ Neil Diamond: Solitary Man. Gifted with knack of writing pop songs with musical and emotional hooks, Diamond took years to discover who he was. Ironically, that allowed him, following a number of sold-out shows at L.A.’s Greek Theatre, to become “the Jewish Elvis.”

As David Wild of Rolling Stone says: “He was selling sensitivity, raw sensitivity that’s not allowed anymore.” This taut BBC documentary serves up all you’d ever want to know about the creation of “Sweet Caroline,” “Cracklin’ Rosie” and “I Am, I Said” from the creator himself. As well as fine archival footage of Diamond at The Bitter End in the 1960s, plus talking heads from record execs to Neil Sedaka and Robbie Robertson.

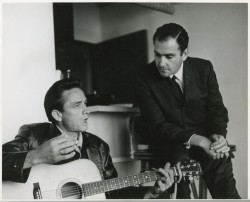

Diamond began working with legendary record producer Rick Rubin a few years ago, after Rubin revived Johnny Cash’s career with American Recordings when the man in black covered “Solitary Man.” An intriguing addition to the Cash iconography is Jonathan Holiff’s My Father and the Man in Black, in which a son’s desire to discover a father he never knew leads him down the path of showbiz arcana: Holiff’s father Saul managed Johnny Cash, when the singer wasn’t the most reliable act in show business. And Holiff fils has the phone recordings, the audiotape journals, the letters and the memento-filled boxes to prove it. What the film may lack in style, it makes up for in substance.

A low-key hymn to finding love amidst the loneliness of urban life, Marco Del Fiol’s Second Movement for Piano and Needlework is a curious piece of cross-cultural pollination set in Sao Paolo’s Jewish quarter. After leaving the park where she’s been sketching dress designs, a woman is drawn to a modal tune on a piano being played by a Korean man. We watch these strangers continue their workaday lives until by chance they meet again. The pianist is sweet and so, in its simplicity, is this minimal movie.

In 1980, Neil Diamond starred in an updated version of The Jazz Singer (the songs he wrote for it made the soundtrack album a hit). In 1959, Jerry Lewis starred in The Jazz Singer for the TV show, Startime. TJFF is showing a restored version of this well-regarded vintage nugget on a program with Mehrnaz Saeedvafa’s short film, Jerry and Me. Before you scoff, the stars of two subsequent films directed by The Jazz Singer’s director, Ralph Nelson, went on to win Best Actor Academy Awards – Sidney Poitier in Lilies of the Fields Cliff Robertson in Charly. Ms. Saeedvafa, meanwhile, confesses in her film clip-packed 38 minutes that “the hero of her childhood [in pre-revolution Iran] was the one and only Jerry Lewis.” She personalizes colonialism, the CIA, Bresson and poetic cinema, the Iran-Iraq war, feminism and fear of the atomic bomb. And as a bonus, we see Jerry Lewis dubbed into Farsi. If you think that’s farcical, you’re right.

What Joe Papp and “Shakespeare in the Park” did for Don Byron: “When you got people of colour doing Shakespeare, then Shakespeare was mine. And then Sondheim was mine, Mahler was mine and Bartok was mine.” What Don Byron did for Tracie Holder’s and Karen Thorsen’s straightforward documentary, Joe Papp in Five Acts: he composed the tuneful, lively score for it.

Three films unavailable for previewing promise some intriguing musical insights.

Broadway Musicals: A Jewish Legacy, directed by Michael Kantor focuses on the central question: Why has the Broadway musical proven to be such fertile territory for Jewish artists of all kinds? Peter Bradshaw wrote in The Guardian that Laurent Bouzereau’s Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir “is strongest in elucidating the effects his life has had on his movies. Before this, I didn't realise how closely the 2002 film The Pianist was based on precise childhood memories of the Krakow ghetto. It is the film he says he is proudest of now.” Danny Ben-Moshe’s Shalom Bollywood: The Untold Story of Indian Cinema tells of the 2000 year old Indian Jewish community and its formative place in the Indian film industry. Who knew? Nu?