“...as the story unfolds”: Theaturtle’s ‘Charlotte’, 2017 to today

On June 1, I had the opportunity to see Theaturtle's Charlotte: A Tri-Coloured Play with Music at Hart House Theatre. A three-way collaboration between Canadian librettist (and Theaturtle's artistic director) Alon Nashman, British scenographer Pamela Howard and Czech composer Ales Brezina, this was the only performance in Toronto before the company goes on a world tour. Two years ago, an earlier work-in-progress version of Charlotte was presented at the 2017 Luminato Festival before touring abroad for the first time, and I became fascinated by the show and the creative team's innovative approach.

On June 1, I had the opportunity to see Theaturtle's Charlotte: A Tri-Coloured Play with Music at Hart House Theatre. A three-way collaboration between Canadian librettist (and Theaturtle's artistic director) Alon Nashman, British scenographer Pamela Howard and Czech composer Ales Brezina, this was the only performance in Toronto before the company goes on a world tour. Two years ago, an earlier work-in-progress version of Charlotte was presented at the 2017 Luminato Festival before touring abroad for the first time, and I became fascinated by the show and the creative team's innovative approach.

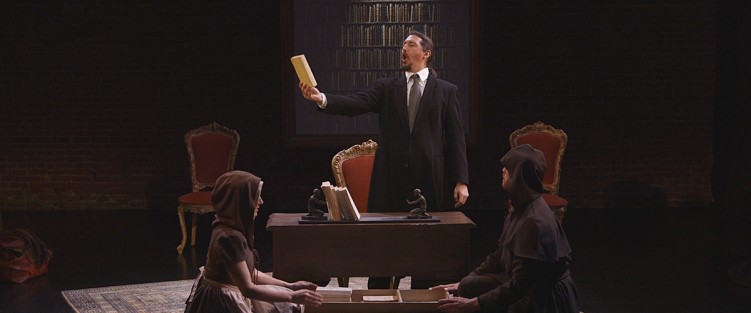

Inspired by the autobiographical series of 700+ gouache painting/collages entitled “Life? Or Theatre?” created by the young German Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon in the two years before her death at Auschwitz in 1942, the design of the costumes and props are taken literally from Charlotte's art. They are stylized, colourful, and evocative of a slightly surreal version of Germany and southern France in the 1930s and 40s; surrounding the stage are thin plastic sheets daubed with splashes of paint, meant to evoke the tracing paper with which Charlotte covered her creations. The music and text notes she made as part of her collages inform the libretto and music as much as the drawings inform the physical design, the creators aiming for a complete synchronicity of word, image and music to immerse us in her world.

According to Nashman, the team approached the musical aspect of the project as a singspiel in the Brecht/Weill tradition. “It is neither opera nor musical, even it it contains elements of both,” he explained to me last month. “There are moments of bitterly ironic cabaret, classical music references turned on their heads, some intense vocal experiments and contemporary sound poems.”

The script follows the story depicted in Charlotte's art (although the approach has changed quite a lot since the first time I saw it – more on that shortly). At heart, as the creative team feel, it is a real story that still resonates today, particularly now when people around the world are suffering under a frightening upsurge of far-right politics. Yet it is not so much a story about the rise of Nazism, but a young girl's journey to selfhood and her struggle to understand what is right in a world full of horrors – a girl who chronicled this coming-of-age during the rise of fascism as if she somehow knew that her own time was short. She was only 26 when she died.

What caught me so strongly in the 2017 workshop performances was the depiction of this struggle not to let the horrors, or horrible decisions Charlotte herself has to make, destroy her soul or spirit. I felt that there was still work to be done tightening and strengthening certain parts of the storyline, but this central theme shone through at the end of the play, making it a satisfying, as well as fascinating (although sometimes rather uncomfortable), experience.

Given this reaction to the original work-in-progress, my expectations of the revised version I saw on June 1 were very high. Reaching out before the performance to ask about how much the production might have changed, I learned from Nashman that “the past two years (had) been devoted to a process of refining and deepening.”

Interestingly, my original expectations of where the revisions and changes would happen were very different from where they actually did. One of the things I had liked best in 2017 was the opening sequence: in real time, in the south of France, we meet the parents (father and stepmother) looking for any tangible trace of Charlotte left behind after the end of the war. They are handed a paper-wrapped package which turns out to be the series of over 700 paintings she had created while exiled in France. As her parents start to look through the artwork exclaiming at memories from their past life together, Charlotte herself comes onstage and starts to tell us about the paintings and the people in them. As I wrote in my notes at the time, this opening offered an easy entrance into Charlotte's story – “grabbing our interest in a gentle way then segueing into the storytelling itself. As the story jumped ahead, Charlotte would pop out of the frame now and again, anchoring us and connecting us to each time period and introducing us to anyone new who entered the story.

In the 2019 version this opening is gone, and is replaced by a new prologue for Charlotte alone with her paintings which then leads into the autobiographical story depicted in her artwork. In this new version, rather than occasionally “popping out of the frame,” Charlotte is very much the narrator from beginning to end.

This fits with what Nashman had told me about the revision process. “Watching the video and reflecting on the 2017 productions at Luminato and the World Stage Design Festival, I came to realize that Charlotte had to be kept in the centre of the frame, that her voice needed to be even more present,” he explained. “I worked with dramaturge Ellie Moon, and found ways to bring Charlotte, both as creator and subject of the paintings, into sharper focus.” This he has done – but in moving away from the more naturalistic original opening and the more subtle introduction of Charlotte, something has been lost, and she has become a much less sympathetic character.

I felt the same way about the new ending. In the 2017 version, we realized in theatrical real time along with Charlotte the true horror of her family's history of suicide, and were caught up with her (as I wrote in my notes then) as she is torn apart by the need to decide whether she should kill her predatory grandfather ‘as one kills an evil rat with poison,’ and as her memories of her lover lead her to choose life and creation instead of death.

In the new version, Charlotte talks about the decision she made, but without sharing the process with us in real time, and so it becomes a less personal moment, and to me felt less uplifting as a consequence.

The tone of the play is altered further by a change in the direction. There is now a more stylized physical acting approach for all the characters, a broader and sometimes over-the-top attack on character creation, particularly when actors are playing secondary parts (there is a lot of doubling), an approach that not all the company seem comfortable with. Thinking about this now, I wonder if the creative team is wanting to move toward a more thoroughly Brechtian approach to telling Charlotte's story: an approach that would use Brecht's famous “alienation effect” to present the story in a less personal or naturalistic style, using instead broader dramatic strokes and shocking juxtapositions to awaken in audiences, as Nashman said he hoped the new version would do, “a greater sense of amazement and loss as the story unfolds.”

The character of Charlotte is presented in a brasher, more modern way, with little vulnerability (though this may be partly due to changes in casting). This could be taken even further. For example, in the new version there is no indication that Charlotte is dead or that she died soon after completing her series of paintings. Looking back at the opening scene, I would have liked her to say to us, straight out, something like: “I died in Auschwitz when I was 26. Somehow I knew that I had to record my life and hope in my art as quickly as I could.” A clearer differentiation between the narrative bridges and the story sequences throughout would have made both more effective.

Before seeing the new version, I had asked Nashman if he thought that the show was in its final form. His reply: “From everything I have experienced, music theatre demands a much longer development period than a play. There are so many creators, so many moving parts. I suspect that we will continue to tinker, but I would say that we are getting close to the final form.”

I am very curious to see how Charlotte: A Tri-Coloured Play With Music will continue to evolve as the production visits festivals around Europe and is experienced by different audiences. Will the company go 'all out' in the direction of a very stylized physical presentational performance, or go back and reincorporate some of the best bits of the earlier, more naturalistic storytelling? Whichever direction they take, this is an important story – and a fascinating theatrical production to experience.

Theaturtle presented Charlotte: A Tri-Coloured Play with Music, at 2pm on June 1, 2019, at Hart House Theatre, Toronto.

Jennifer Parr is a Toronto-based director, dramaturge, fight director and acting coach, brought up from a young age on a rich mix of musicals, Shakespeare and new Canadian plays.