Concert report: “The Human Voice/La Voix Humaine” makes for fascinating programming, digital or live

On February 5, Toronto’s Voicebox: Opera in Concert (OIC) made its digital debut with a fascinating double bill: The Human Voice and La Voix Humaine. This choice of material—an English-language version of Jean Cocteau’s 1928 play, paired with the 1958 Poulenc opera inspired by it—was in part, according to OIC general director Guillermo Silva Marin, in tribute to OIC founder, the late Stuart Hamilton, who first programmed these two pieces together in 1975. It also, however, makes for a perfect entry into digital pandemic programming. That both are solo pieces is ideal for working in a state of safety from infection—and also creates a great opportunity to showcase top talent and virtuosity, in this case the outstanding Chilina Kennedy and Miriam Khalil.

On February 5, Toronto’s Voicebox: Opera in Concert (OIC) made its digital debut with a fascinating double bill: The Human Voice and La Voix Humaine. This choice of material—an English-language version of Jean Cocteau’s 1928 play, paired with the 1958 Poulenc opera inspired by it—was in part, according to OIC general director Guillermo Silva Marin, in tribute to OIC founder, the late Stuart Hamilton, who first programmed these two pieces together in 1975. It also, however, makes for a perfect entry into digital pandemic programming. That both are solo pieces is ideal for working in a state of safety from infection—and also creates a great opportunity to showcase top talent and virtuosity, in this case the outstanding Chilina Kennedy and Miriam Khalil.

Cocteau’s play La Voix Humaine (1928) and Francis Poulenc’s 1958 opera of the same name, inspired by the play, tell the story of a nameless woman (“She” or “Elle”) in torment at the end of a love affair, longing and waiting for a phone call from her lost lover. That phone call, after several wrong numbers, makes up the whole of the play/opera. A woman alone in her apartment, her only connection with the outside world her phone, feels like an uncanny parallel to the lives so many of us are living now, prohibited from spending time with anyone outside our “bubbles.” When you have a bubble of one, the loneliness can be unbearable. This is the case with “She” in The Human Voice, alone on her end of the phone call and doing everything to win her lover back while knowing she has lost him forever.

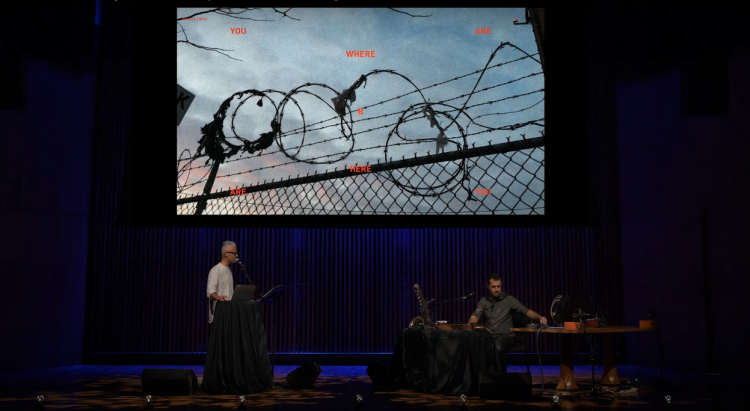

According to biographies of Cocteau, the actors in his company had been complaining of coming second to directorial and design concepts in his productions. Taking up the challenge, Cocteau created this one-woman play that needs, even demands, a bare staging, so that the audience’s attention is clearly focused on the story and the virtuosity of the performer. In the OIC-streamed production, both play and opera take place in the same setting, a living space delineated by starkly white furniture arranged around the familiar confines of OIC’s Edward Jackman Studio. The setting is simple while also giving opportunity for movement and levels of action, and highlights the differences between the spoken and sung versions of the story as we watch both in the same space.