Bosch’s Ergot and Benedetti’s Four Seasons

Not being an art critic, and indeed like most musicians completely unable to draw anything beyond crude stick figures, I find the iconography of Renaissance paintings difficult to interpret. I am however, willing to bet that the images in a typical painting by Hieronymous Bosch are bizarre enough to give most art critics a conniption fit trying to figure out what they are supposed to mean.

Not being an art critic, and indeed like most musicians completely unable to draw anything beyond crude stick figures, I find the iconography of Renaissance paintings difficult to interpret. I am however, willing to bet that the images in a typical painting by Hieronymous Bosch are bizarre enough to give most art critics a conniption fit trying to figure out what they are supposed to mean.

Some scholars argue that the Flemish painter’s fanciful and often downright weird imagery should be read allegorically, as it was intended to lampoon both contemporary mores as well as a hypocritical clergy, while others argue it was proof that Bosch was on a drug trip, specifically ergotism (google “St. Anthony’s Fire”). I’m unwilling to come down on either side of the debate, but I would like to volunteer the possibility that a certain amount of Bosch’s work was a nascent form of art for art’s sake. I mean, given the opportunity, who wouldn’t want to paint a man shitting out a flock of blackbirds while being eaten by bluebird-headed monsters?

What’s interesting for musicians about Bosch is how much music is in his work, and that he clearly finds a great deal of it immoral. Like it isn’t even subtle. In The Ship of Fools, a monk and nun sing along with the boat’s drunken passengers (one of whom is seen retching over the side, having overimbibed) while accompanied by a lute. In The Haywain, a cart of hay is being pulled by a creepy looking crowd of animal-headed demons toward hell and everlasting damnation. The haywain’s main passengers, a man and woman, are oblivious to this despite the apparent entreaties of both a guardian angel and the appearance of Christ a few feet above their heads – they’re too busy studying a piece of printed music in front of them while a white-robed lutenist plays for them, accompanied by a faceless blue demon on an eldritch clarinet.

While I doubt the examples above mean Bosch was completely against music in all its forms, they do show he was not only concerned about music’s ability to corrupt otherwise good people, but was someone who believed that music had a very real power to influence the character of its practitioners and listeners, and that music-making was just as much an ethical experience as it was an aesthetic one. It’s perhaps in this spirit that the Toronto Consort is presenting the Cappella Pratensis as part of its special guest series. The Canadian-led ensemble – their artistic director is Stratton Bull, a native of Cobourg, Ontario, with degrees from U of T and the Royal Conservatories of Toronto and The Hague – is a Belgian-based group that has made Franco-Flemish music its specialty, and their concert, on March 3 and 4 at 8 pm at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre is devoted entirely to composers based in Belgium whose music would have been performed in Bosch’s lifetime.

Although few music lovers in Canada go out of their way to praise Belgian composers, the country was the source of the leading composers of polyphony from the early Renaissance, so Pratensis has a wealth of music to choose from. This concert will likely feature the Missa Cum Jocunditate by Pierre de la Rue from the group’s latest album, released last year to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the painter’s death. If you’re interested in Renaissance music, this is a very interesting concept for a concert program and Cappella Pratensis is a group that has mastered the art of polyphony.

Catch this concert if you can.

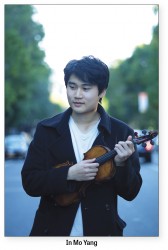

Nicola Benedetti: Cappella Pratensis isn’t the only international early music group to show up in town this month. Already with eight recordings under her belt, superstar 29-year-old Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti is a seasoned performer of violin pyrotechnics. She’s already recorded the Bruch and Korngold violin concertos, Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending, Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, and Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major Op.35, which in the modern classical world makes her a wunderkind. “But can she play early music?” is probably the main question critics and concertgoers will ask, and I’m excited to hear what the answer to that question will be. Benedetti will answer it when she appears with the Venice Baroque Orchestra, itself a very fine performing ensemble, under the direction of the Italian harpsichordist Andrea Marcon.

They’ll be playing a massive program of Italian works meant, one assumes, to highlight Benedetti’s formidable talents. But even a talented young superstar and orchestra will have to work hard to hold the audience’s attention for the entire Four Seasons by Vivaldi (itself of full CD length); Avison and Geminiani concerti grossi, a Galuppi concerto, and another Vivaldi concerto are tacked on to the program, for good measure. This kind of show can easily clock in at two and a half hours, and if done well can be an absolutely sublime experience – anything less and the audience will feel like they’ve been beaten into submission. Benedetti’s clearly intended to be the main event in this concert, and this will be a great opportunity to get a look at a brilliant young soloist who can cross over between modern and early repertoire with ease. She has been a regular visitor to Toronto concert halls and will hopefully return in a similar capacity. You can catch this concert as part of the Royal Conservatory’s string series on March 3 at 8 pm at Koerner Hall.

Cor Unum: It’s always good to see new groups on the music scene, and there’s a new group in particular in Toronto that I’ve been meaning to write about for some time now. The Cor Unum Ensemble formed late last year and despite being under a year old is already putting together some ambitious concerts of difficult repertoire. This month, they’ll be playing the St. John Passion by Bach along with the violinist Adrian Butterfield, who will be filling in as guest director of the ensemble. Butterfield is not so well known outside of the United Kingdom, where he is one of the co-founders of the London Handel Players, but he has a dozen recordings to his name that mainly feature late-Baroque and early classical works. He also has the unique honour of being the resident Naxos recording artist for the label’s collection of the complete sonatas of Jean-Marie Leclair, so branching out from Handel and the mid-18th century to Bach seems like a logical shift in repertoire for this chamber player. For its part, Cor Unum is mainly a group of younger players who are both new to early music and the Toronto music scene, and it will be interesting to see what the group will be able to accomplish when under the direction of a veteran player like Butterfield. Youthful vigour applied to standard repertoire like the St. John Passion can make for exciting results, especially combined with the guidance of a leader who is experienced in early music performance practice. Catch this concert at Trinity College Chapel on March 12 at 7:30pm.

Stylus fantasticus: Finally, if your interests lean more towards chamber music than vocal or orchestral extravaganzas, consider checking out a program dedicated to a musical movement from the early Baroque known as the stylus fantasticus. It isn’t particularly well-known today, meriting a mere stub of an article in most musical encyclopedias, but without the stylus fantasticus, Western instrumental music as we know it would likely not exist. It was first mentioned by the Jesuit and polymath Athanasius Kircher, who, writing in 1650, described the stylus fantasticus as “the most free and unrestrained method of composing, bound to nothing, neither to any words nor to a melodic subject; [it] was instituted to display genius and to teach the hidden design of harmony and the ingenious composition of harmonic phrases and fugues.” Certainly before the Baroque era, the chance to compose music freely wasn’t really a possibility for composers. Musical form was largely limited to either the repeating rhythms of dance forms or based on a set melody like a Gregorian chant. Not only was the stylus fantasticus the first chance for composers to test their creativity, but it brought new prominence to the potential of instrumental, rather than vocal, music.

Four hundred years later, it’s easy to see what got Kircher so excited: no instrumental music means no symphonies, and no freedom of form means no sonatas or other compositions that can develop over a couple hundred bars. For the first time, composers, or competent improvisers, could let their imaginations roam freely, limited only by their knowledge of harmony or their technique. Rezonance (full disclosure, I am a founding member of the group) will be performing Italian and Austrian works in this style from the early 17th century as part of the Hammer Baroque series at St. John the Evangelist Church in Hamilton (320 Charlton Avenue West) on March 18 at 4pm, and at Gallery 345 on March 19 at 3pm. If you’re looking for an out-of-the-box chamber music concert this month, this is a concert that invites you to enjoy composers who broke free from tradition and cliché and gave listeners a chance to hear musical creativity at its most expressive. You’ll definitely enjoy what they dreamt up.

David Podgorski is a Toronto-based harpsichordist and music teacher. He can be contacted at earlymusic@thewholenote.com.