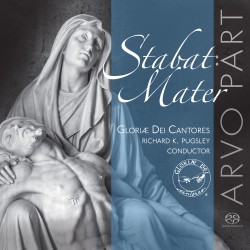

Arvo Pärt: Stabat Mater - Gloriae Dei Cantores; Richard K. Pugsley

Arvo Pärt – Stabat Mater

Arvo Pärt – Stabat Mater

Gloriae Dei Cantores; Richard K. Pugsley

Gloriae Dei Cantores Recordings GDCD065 (naxos.lnk.to/StabatMaterEL)

If any composer could, singlehandedly, have created a public receptive to the holy minimalism of John Tavener and Górecki’s third symphony, it would be the monkish Estonian, Arvo Pärt whose 85th birthday (September 11) was the occasion of this release. Pärt‘s music has evolved through serialism – using the dissonances of atonal music – and Franco-Flemish choral music until, after years of meditation, religious consultation and even a break from composing, Pärt settled into using his singular voice to initiate his enduring tintinnabuli period, featuring such masterpieces as Tabula Rasa, Fratres and Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten.

This disc takes its name from Stabat Mater but also consists of other masterfully performed still and contemplative choral works. As with Pärt’s orchestral pieces, the uniqueness of this choral music is achieved largely through a build-up of dynamics and contrasting sonorities used in an almost circular manner. The Magnificat and Nunc dimittis are particularly eloquent examples.

The longest work is Stabat Mater. While this music is intense, Pärt eschews the pain of the crucifixion; rather he imbues the event’s sadness with a ritualistic element by way of the gently rocking motion that forms the basis of the work. You couldn’t ask for a better end to this disc. Yet the build-up to it is extraordinary because Gloriæ Dei Cantores, directed by Richard K. Pugsley, has interiorized Pärt’s spirit – indeed his very soul – as they traverse his music to an unprecedented degree of poignancy, with beautifully moulded choral textures and colours.