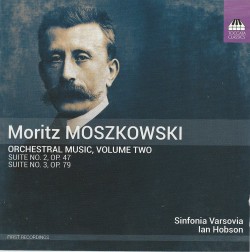

Moritz Moszkowski: Orchestral Music Volume Two - Sinfonia Varsovia; Ian Hobson

Moritz Moszkowski – Orchestral Music Volume Two

Moritz Moszkowski – Orchestral Music Volume Two

Sinfonia Varsovia; Ian Hobson

Toccata Classics TOCC 0557 (naxosdirect.com/search/5060113445575)

Fate was surely unkind to the once-celebrated composer and conductor, Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925): his marriage ended, his teenaged daughter died, avant-garde movements rendered his compositions “old-fashioned” and his considerable fortune disappeared when World War I obliterated his investments. After years of failing health, he died an impoverished recluse in Paris.

Until the recent revival of interest in lesser-known Romantic-era repertoire, all that survived in performance from Moszkowski’s large output were a few short piano pieces that occasionally appeared as recital encores. Nevertheless, it’s hard to believe that his Deuxième Suite d’Orchestre, Op.47 (1890) is only now receiving its first-ever recording – it’s far too good to have been ignored for so long!

The 41-minute, six-movement work begins with the solemnly beautiful Preludio, in which extended chromatic lyricism builds to a near-Wagnerian climax. The urgent, increasingly furious Fuga and syncopated, rocking Scherzo suggest Mendelssohn on steroids. The long lines of the lovely Larghetto are warmly Romantic, gradually blossoming from tranquil to passionate. The cheerful, graceful Intermezzo leads to the Marcia, a surging blend of Wagner and Elgar that ends the Suite in a proverbial blaze of glory.

Moszkowski’s Troisième Suite d’Orchestre, Op.79 (1908), in four movements lasting 27 minutes, is much lighter and brighter, almost semi-classical in its sunny charm. The robust playing of Sinfonia Varsovia under conductor Ian Hobson adds to this CD’s many pleasures. Here’s winning proof that there’s lots of “good-old-fashioned” music still waiting to be rediscovered and enjoyed!