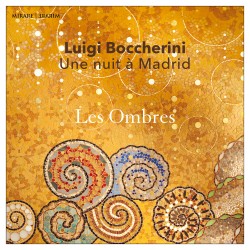

Luigi Boccherini: Une nuit à Madrid Les Ombres

Luigi Boccherini – Une nuit à Madrid

Luigi Boccherini – Une nuit à Madrid

Les Ombres

Mirare MIR524 (mirare.fr)

If Boccherini had never moved to Spain – ultimately regarding it as his native country – the world might have been denied much of his fine chamber music composed for the brother of King Charles III, the infante Don Luis. His move wasn’t entirely smooth – he referred to local musicians as “inveterate barbarians” – but the Spanish influence on his musical style was not an insignificant one, evident in such pieces as the renowned “Fandango” quintet, one of five quintets presented on this splendid Mirare recording performed by the Basel-trained ensemble, Les Ombres.

Of those featured here, three are for flute and strings – Nos.2, 4 and 5 from the set of six quintets Op.19. These are remarkable not only for their brevity (each comprises only two movements and is less than ten minutes in length) but for their diversity. The second has a dark and impassioned mood, while the fourth begins with a solemn adagio followed by a gentle minuet and the fifth is all rococo grace.

Of greater scope is the four-movement Quintet G451 in E Minor. Despite the inclusion of a guitar, there is no Spanish element to this music, but the instrumental blend is an appealing one and Les Ombres perform with a solid conviction, at all times maintaining a delicate balance among the instruments.

The highlight of the disc is surely the Quintet No.4 G448 known for its spirited Fandango finale. Performed with great panache – with the help of clacking castanets and Romaric Martin’s fine guitar playing – the movement is infused with Mediterranean exuberance – music that seems made for dancing!

Fine acoustics on this recording further enhance an exemplary performance throughout – bravo a todos!

Reincarnation – Schubert; Messiaen

Reincarnation – Schubert; Messiaen