Remembering Neil Crory

Genius, if the word has any meaning at all, comes in many forms. There’s the exuberant, demonstrative, egomaniacal, smoking-hot pistol of genius – think Glenn Gould.

Genius, if the word has any meaning at all, comes in many forms. There’s the exuberant, demonstrative, egomaniacal, smoking-hot pistol of genius – think Glenn Gould.

But there’s also a quieter form of whatever genius is – and if it’s anything, it is originality combined with integrity, uncompromisability, single-mindedness, assurance.

And by that definition, Neil Crory had genius.

Neil, friend to so many, longtime CBC Music producer, writer, mentor, proselytizer, imp, beauty, died on January 10, after he and the Parkinson’s disease which had invaded him a decade earlier had finally had enough of each other and decided to part ways in mutual disgust. Neil, to the disease’s fury, had bent to its destructive evil, but had never broken.

Working at CBC Radio Music, as I had done for decades, meant that I knew of Neil Crory. He was the ultimate music producer, famous for his discoveries and crusades, picky, prickly, notoriously indulgent with other people’s money, hard-nosed to a fault, a bit of an elitist, slow in his projects and obsessions, not everyone’s favourite colleague. In fact, far from everyone’s favourite colleague. It always used to make me laugh that a radio department devoted to musical artists never really knew what to do when it actually stumbled across one.

I knew of Neil Crory, but never really knew him until 2007, when I was handed an unenviable assignment – to produce a single, four-hour long, weekend classical music program, hosted by Bill Richardson (another artist people were confused by) called Sunday Afternoon in Concert. Today, the program is simply called In Concert, is still four hours, and is produced by Denise Ball in Vancouver and very ably hosted by Paolo Pietropaolo. Denise and Paolo approach their monstrous broadcast time like any sensible production team – they divide their program into sections and segments and weave a tapestry of music throughout their program. They do a fine job.

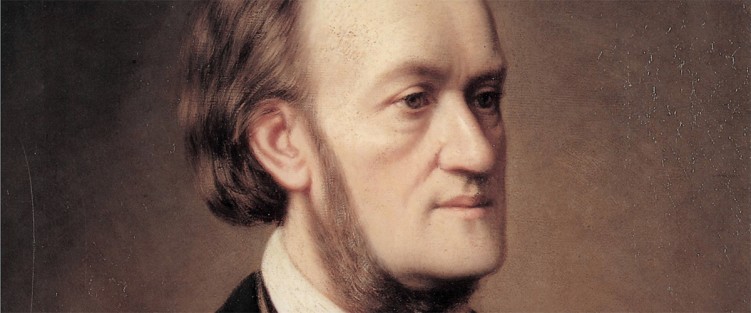

However, for reasons I now forget, I decided not to follow this approach with Sunday Afternoon in Concert. I wanted instead to do the impossible – weave a single theme through a four-hour long broadcast, create a program that was not a kaleidoscope of various parts, but a unified whole unfolding over four hours, a Wagnerian opera of a radio program, different every week. It was insane, counter-intuitive (no one listens for a four-hour long period of time), impossible. Everyone thought I was crazy. Everyone, that is, except Neil Crory.

I’m not sure whether the mischievous imp in Neil was simply attracted to the sheer perversity of what I was trying to do. I’d like to think he shared my enthusiasm for trying something different. For whatever reason, he became my chief partner in crime, with his awe-inspiring ability to come up with novel programming and repertoire selections. He didn’t contribute to every program, but the ones he did contribute to were very special. Our mutual boss, Mark Steinmetz, told me once that Neil had come up to him after one of my shows – the four-hour Bach show where we played, among other things, two versions of Brandenburg 5 by two different Canadian orchestras, back to back – and told Mark he thought SAIC should be taken off the air. “Why?” Mark asked. “Because it’s too good,” was Neil’s reply.

It remains the single best compliment I’ve ever received in 40 years in the business.

But the true worth of Neil Crory’s talent, and genius, and the love and respect he inspired was in evidence when Sunday Afternoon in Concert decided to present a live Christmas concert in the Glenn Gould studio in mid-December 2007. It was one of the first things we talked about at our first story meeting in September. Neil said he’d produce it, and rolled off a roster of A-list Canadian opera stars that he’d try to convince to come perform. All the greats Neil had discovered and mentored and encouraged and inspired when they were just starting out, now regularly appearing in the greatest opera houses in the world. We all looked at each other in disbelief. A concert like that would take a normal person six to eight months to pull off, if they could pull it off at all. Neil assured us it would work. We believed him.

And then, because these things happen, we got busy and Neil got busy, and it was now the first week in November and we really hadn’t done anything at all to plan the Christmas show. I convened a special meeting where we all reluctantly agreed that we’d have to shelve the live concert idea until next year. All, that is, except Neil. No, he said, I think we can make this happen. In five weeks? Yep. Five weeks? Let me see what I can do.

And, of course, he pulled it off.

It wasn’t quite Michael Schade saying to the Vienna State Opera – sorry, you’re going to have get someone else to perform Tamino next Tuesday – I have to go back to Canada to sing Christmas carols in front of 250 people in the Glenn Gould Studio because Neil Crory asked me to, but it was damn close. Performers who are routinely booked five years in advance all showed up within a month’s notice because Neil asked them to – Schade, Russell Braun, I don’t think Isabel Bayrakdarian could make it, but many other stars were there. The green room was such a Who’s Who of Canadian vocal talent you couldn’t help but laugh in astonishment at the treasures all assembled in one place. I on the other hand, wasn’t laughing. As the executive producer of a show that came together so quickly -- was there even a dress rehearsal, don’t think so – I sat in the audience in anxious anticipation, until the first act strode on stage – I think it was two brothers from Newfoundland – and thereafter spent the entire afternoon in blissful tears. It was one of the greatest things I ever witnessed – and it was all Neil – the love in the room, the excellence on stage, the commitment of the performers , the passion behind it all – it was everything that Neil Crory represented coming to life and exploding in beauty in one tiny concert hall one December afternoon. It was special, to say the least. It was Neil.

Of course, sadly, Neil was predeceased by about a decade by the CBC Radio Music department he loved and had helped shape. It’s a tale for another day, but the destruction of CBC Radio Music remains, whether noticed or not, acknowledged or not, one of the great moral and artistic tragedies of Canadian cultural life. The organization that helped create everyone from Glenn Gould to… well, to Neil Crory, was a beacon for creativity and originality in this country, and the world beyond, and it was snuffed out in a blizzard of bad ideas, creative amnesia and Lilliputian thinking in a matter of a few months. The end of Radio Music didn’t kill Neil Crory, but it didn’t inspire him in his later years, either.

I’m told that Neil died listening to Schwarzkopf singing Strauss, a fresh yellow rose in his lapel, surrounded by friends, a true producer to the end. Those of us who were touched by him, who felt the breeze of his unique presence pass by us and change the atmosphere around us, won’t forget him, ever. A country produces few individuals with his depth of humanity, caring, intelligence and wit. Another like him won’t be coming along any time soon.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.