Robin Engelman (1937 – 2016) - Intersecting with His Percussive Life

As I write this, Robin Engelman’s website is filling up with dozens of tributes, both moving and humorous, from around the world. CBC Radio broadcaster Tom Allen, on his show Shift, eulogized Robin for his “voracious love of life and pursuit of knowledge,” for his “integrity and passion for getting things right.”

Percussionist, music teacher, composer, oenophile and amateur golfer Robin Engelman had an active musical career ranging over half a century conducted at the highest artistic level, so perspectives on his life and work will be many, varied and likely, as often as not, focused as much on the individuals he influenced as on Robin himself. He enlivened many lives, mine included. Here is my take on it.

His musical path began in the US, but his distinguished contribution to Toronto’s musical life was wide and deep. As a percussionist he had extended engagements with our symphony orchestra under the eminent conductors Seiji Ozawa and Karel Ančerl, our opera company, and for more than 15 years with New Music Concerts. It was, however, his nearly four decades performing with Nexus that most keenly defined his career as a musician.

His musical path began in the US, but his distinguished contribution to Toronto’s musical life was wide and deep. As a percussionist he had extended engagements with our symphony orchestra under the eminent conductors Seiji Ozawa and Karel Ančerl, our opera company, and for more than 15 years with New Music Concerts. It was, however, his nearly four decades performing with Nexus that most keenly defined his career as a musician.

Being an avid Toronto concertgoer and an active contemporary music student, then musician and composer, I witnessed and savoured Robin’s work in each of his roles from the 1960s on. Witnessing him among his varied colleagues in the act of musicking proved to be defining musical moments, keys of inspiration. They helped to unlock the doors of my own musical journey.

He was also a passionately critical teacher and musical mentor to generations of percussionists. Though I was never formally his student, our paths first crossed at York University in the early 1970s. I was already an undergrad there, focused on the bassoon, composition and ethnomusicology, when Robin made his presence known, and felt, as an instructor of percussion there. His studio at Founders College, chock-a-block with orchestral and non-Western percussion instruments, was heady turf for young musical keeners like me.

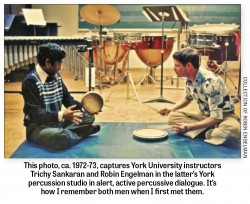

In this early 1970s photo, Engelman is playing the standard drum practice pad with an intense musical focus, not on his instrument his hands or thoughts, but rather on his musical partner of the moment. With drumsticks in hand, he’s tackling “Three Camps” (according to his own caption to the photo) with his illustrious York University colleague, my teacher and later fellow performer, Trichy Sankaran, here playing the kanjira. They’re surrounded by the tools of Robin’s trade. Looking closer, we see they’re poised like two dancers, the tension and excitement of their musical dialogue palpable in their body language and gaze.

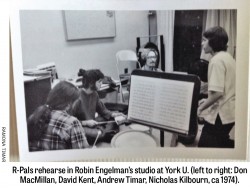

With minimalism in the York air – and Nexus right in the thick of it (more on that later) – I started a student percussion-centric group which made its own music cheekily tagged R[hythm] Pals. Robin encouraged me and permitted us to rehearse at his studio. He also generously allowed us to use his instruments, including the kulintang, a gongchime from the Southern Philippines, which I played extensively in the ensemble in concerts at York, A Space, The Music Gallery and at the University of Western Ontario, London. That kulintang, the gong ensemble in which it is featured, R-Pals, as well as the numerous performances of Nexus I attended at the time, were all determining factors in setting the tone for my lifelong taste for the sounds of percussion, and more specifically, gong ensembles.

That specific sonic taste for gongs has morphed into a career-long deep and abiding affection, exemplified most enduringly in my 33 years with Toronto’s Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan, Canada’s pioneering ensemble of its kind. Robin had, over the decades, attended a number of ECCG concerts, partly because he was genuinely passionate about avant-garde music, but in large part I think, in order to support – and sometimes challenge – the local community of percussionists, many of whom considered him a mentor. As more of his former University of Toronto students began to perform with the group, Robin made it a point to see what we were doing. In 2014, he even published his review of an ECCG concert on his website. Following a lifelong practice of telling it as he saw and heard it, he pulled no punches!

That specific sonic taste for gongs has morphed into a career-long deep and abiding affection, exemplified most enduringly in my 33 years with Toronto’s Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan, Canada’s pioneering ensemble of its kind. Robin had, over the decades, attended a number of ECCG concerts, partly because he was genuinely passionate about avant-garde music, but in large part I think, in order to support – and sometimes challenge – the local community of percussionists, many of whom considered him a mentor. As more of his former University of Toronto students began to perform with the group, Robin made it a point to see what we were doing. In 2014, he even published his review of an ECCG concert on his website. Following a lifelong practice of telling it as he saw and heard it, he pulled no punches!

On April 14, Soundstreams will present “Steve Reich at 80,” in celebration of one of the shakers of musical minimalism, and as I had alluded to earlier, there’s a Robin and Nexus connection here too. Nexus co-founders Russell Hartenberger and Bob Becker were both also original members of the seminal Steve Reich and Musicians, formed in 1966. Then, when Nexus was born in 1971 in Toronto, Robin was on board as a charter member. During their many extensive residencies, national and international tours, Robin was there (installments of his tour diaries can be read on the Nexus website). And Reich’s music was often on the program. His minimalist masterwork, Music for Pieces of Wood, videoed in a 1984 Tokyo concert, has surpassed 242,000 YouTube views.

Returning once more to that evocative early 1970s photo of Sankaran and Robin, to me it captures a key feature of that era’s York University music scene and Robin’s place in it. In retrospect, the place was at the beating heart of a kind of transcultural music making, and for a few (trans)formative years I was privileged to be part of it. I’ve spent a career since exploring several such musical broader crossings and meetings. That photo reminds us that Robin’s York studio was one of its early touchstones, while his continuing friendship was yet another. He is already missed by many.

The WholeNote’s regular world music columnist, Andrew Timar, is a Toronto musician and music writer.