TSO: Crises Weathered, Challenges Ahead

It’s been less than two years since the then-chair of the board of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Richard Phillips, and eight of his senior colleagues, including Sonia Baxendale, stunningly and abruptly resigned from the organization one December afternoon. It remains a mystery to this day why they left.

It’s been less than two years since the then-chair of the board of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Richard Phillips, and eight of his senior colleagues, including Sonia Baxendale, stunningly and abruptly resigned from the organization one December afternoon. It remains a mystery to this day why they left.

Had this kind of thing happened at other similar organizations – the New York Philharmonic, or the Metropolitan Opera, let’s say – it would have been front-page news. Here, it barely caused a stir, and since then, Richard Phillips and Sonia Baxendale seem to have been more or less expunged from the history of the TSO. Which is a pity.

Because what’s interesting about Phillips and Baxendale is that without them, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra may well have gone bank-rupt in the spring and summer of 2016. Today, as the TSO is finally achieving some desperately needed organizational stability, it’s hard to imagine how different things were not that long ago. But in March of 2016, after the now-you-see-him-now-you-don’t departure of short-lived TSO president and CEO Jeff Melanson, the TSO was within a few thousand dollars of insolvency. Senior financial officers were ap-proaching department heads to inquire whether there was anything that could be sold to keep the organization afloat. In a situation streaked red with emergency, Phillips and especially Baxendale (who became the organization’s acting CEO, for an agreed six-month term, after Melanson’s departure) steered the TSO ship rockily but successfully to a small surplus in fiscal 2015/16. They accomplished this by applying the appraised value of a valuable TSO viola against the organization’s accumulated deficit (reducing that deficit by four million dollars), con-vincing the Toronto Symphony Foundation to double its annual contribution to the TSO, and one assumes, by writing some generous cheques of their own. For thanks, within eight months they had disappeared from the organization.

Perhaps Phillips’ and Baxendale’s departure was karma for the sin they had committed of hiring Jeff Melanson to be the orchestra’s presi-dent and chief executive officer in the first place. We shall never know the full extent of Melanson’s toxic influence on the TSO, but it can be effectively argued that the organization is just now recovering from it. Before Melanson, the Toronto Symphony had had one CEO for 12 years, Andrew Shaw. In contrast, there have been four changes of leadership since – four administrative regimes in four years. A year and a half of Melanson, six months of Phillips and Baxendale, two years of Gary Hanson as interim CEO, and now a few months of Matthew Loden, the TSO’s just recently appointed CEO.

It is a tribute to the TSO that it has not only survived these ongoing challenges, but has seemed to emerge from them with momentum. The latest annual report showed an operating surplus for fiscal 2017-18 of over two million dollars (although that surplus was buoyed by a $3.2 million grant from Canadian Heritage that will not be repeated next year). Matthew Loden, the new CEO, comes with a fine track record with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The appointment of a new Music Director, Gustavo Gimeno, was announced this fall, to replace the recently re-tired Peter Oundjian, although Gimeno won’t actually take over until the fall of 2020. Throughout all the organization’s troubles and travails, the staying power and continuity of the true heroes of the Toronto Symphony, Loie Fallis, vice-president of artistic planning and Roberta Smith, vice-president and chief of staff, can’t be over-estimated. I’m guessing that the organization’s outgoing and highly popular former mu-sic director should also be included on that list.

The TSO seems to have weathered the existential crises of the past five years, bending without breaking. All arts organizations these days, worldwide, are perched on very delicate financial precipices, the distance between success and catastrophe very short indeed. The real challenge for the Symphony is that the organizational turmoil of the past few years has prevented the orchestra from effectively redefining its artistic mandate and raison d’être in the post-Oundjian era. Andrew Davis has stepped in as the organization’s titular head as the TSO awaits Gime-no, but all of Oundjian’s signature programming initiatives of the past few years have been erased. There will be no Mozart Festival this year, no Decades projects, most distressingly, no New Creations Festival. A city’s symphony orchestra should be the primary musical institution in any metropolis, if only by dint of its size and budget and prestige. But programming counts for something too, and here the TSO is losing that primacy. Tafelmusik is playing these days with greater assurance and self-knowledge, under the inspired new leadership of Elisa Citterio. The Royal Conservatory is outflanking the TSO in terms of New Music, having just moved its successful 21C Festival to January, to fill the gap in the winter calendar where the TSO’s New Creations Festival used to be. The Canadian Opera Company, although not really a TSO competitor, has come to dominate the musical public relations scene in the past few years.

Hopefully, the groundwork has been laid for that to change in the Gustavo Gimeno era. People clearly wish the symphony well and are ex-cited and curious about the new music director. The TSO has already had to add an extra concert for Gimeno’s season-ending appearance with the orchestra this coming June, which is a good sign. Single ticket sales, which have eclipsed subscriptions as a source of TSO box office reve-nue, are also on the upswing. Another positive indicator. A financial plan for stability seems to be within the TSO’s reach, finally. And the current TSO board, led by chair Cathy Beck, extending her family’s long-standing dedication to the Toronto Symphony, looks set to provide a level of continuity to the organization as well.

But the biggest challenge to the Toronto Symphony remains to be addressed. When I spoke to Gary Hanson at the beginning of his tenure as interim president and CEO of the TSO, we talked about the upcoming challenge of replacing Oundjian as music director of the organization. Hanson reminded me that the question that the symphony needed to answer was not who the new conductor would be, but what. In other words, what kind of an organization did the TSO want to become? That used to be a relatively simple question for symphony orchestras in a secure, musical world. It isn’t anymore. Playing the classics beautifully isn’t enough. Or maybe it is. But what about attracting new audiences, reflecting the cultural diversity of the city in which the orchestra is housed, educating people about music, reaching out to other musical communities? It’s not at all obvious where an orchestra should be directing its attention these days. Gimeno is young, which is good, and con-sequently brings few musical expectations with him, which is also good. But it was clear when his appointment was announced in September that he has no idea yet what kind of a place Toronto is, having spent literally no more than a few days in the city up to that point as a guest conductor. But he’ll have two full years to figure that out, along with Matthew Loden, himself just a few months into his tenure.

And more power to them all! We need the TSO to be strong, and it hasn’t been able to be especially so in the last few years. Musicians, and orchestral musicians especially, are notoriously grumpy and dark about life, but music is not. Music is optimistic, bright, life-fulfilling. It is the path that its music creates for it that can give the TSO the hints it needs to secure its future. And we’ll all be the better for it.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.

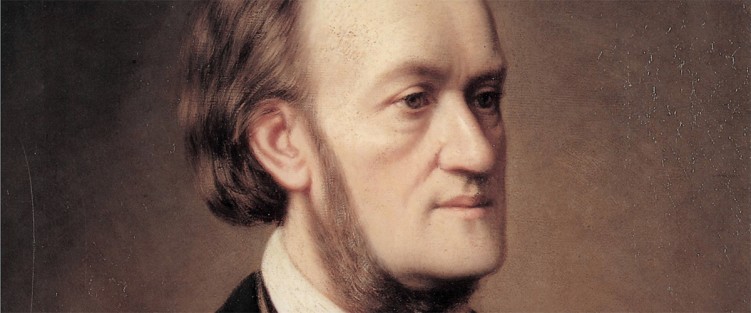

A Jewish Defence of Wagner’s Ring

Charles Heller

The November 2018 issue of The WholeNote ran an article by Robert Harris (“Wagner in the Age of #MeToo”), claiming that the #MeToo movement should stir us to consider Wagner’s Ring as being unacceptable to modern audiences because of its antisemitic message. As a Jewish Wagnerian, here is my response.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of meeting Gottfried Wagner, who, with his penetrating gaze and aquiline nose, conjured up the aura of his great-great-grandfather. He said emphatically: Wagner’s music is great art, the composer and his family were monsters, and we must respect the wishes of those who do not want to hear it publically performed in Israel, a country he loved. He was also of the opinion that fu-ture generations of Israelis, no longer traumatized by first-hand experience of the Shoah, will be able to accept Wagner performances. These views are supported by Israeli music-lovers today.

Richard Wagner said a lot of contradictory and inflammatory things, but when it came to composing music he knew what he was doing. The idea that antisemitism is at the heart of the Ring is preposterous. Mime and Alberich are not Jews, they are dwarves, and they were dwarves when the story was composed in medieval Iceland, where no Jew was ever seen. But people certainly imagined they saw Jewish gestures in Wagner’s dwarves - Mahler complained of one particular performance that it was a ”caricature of a caricature”. But that didn’t stop the Jew Mahler, or his colleague the Jew Schoenberg, from regarding Wagner’s scores as central to Western music. The Ring is not about an evil Jew, it is about what it takes to be oneself and overcome obstacles – overbearing parents (the gods), irrational fears (the giants), brash egotism (the runes on Wotan’s spear) and whatever else is clogging your subconscious mind.

If it were really true that the Ring is an antisemitic diatribe, and that art is to be judged on the morality of the artist, then why stop with Wagner? We still are left with the music of Chopin (who accused Jews of destroying Polish music) and the poetry of T. S. Eliot (who accused Jews of destroying Western culture). Dickens hated Jews too, and don’t get me started on The Merchant of Venice or Caryl Churchill’s play Seven Jewish Children, which despite being intended as an attack on Jews was performed in Toronto with the financial support of the City a few years ago.

Jews have lived with antisemitic garbage for 2000 years, much of it encouraged by the Church and the State. To claim that the Ring is anti-semitic is a perversion of what the Ring and what antisemitism are all about. Antisemitism is alive and well today, both in the twisted minds of far-right thugs in the USA and in far-left politics in the UK and Canada. In the age of #MeToo we must certainly refuse to work with peddlers of hatred and harassment. But Richard Wagner is long dead and his work endures.

Charles Heller is an Associate Composer of the Canadian Music Centre. He is on the editorial board of the Journal of Synagogue Music, published by the Cantors Assembly, New York and is the author of What to Listen For in Jewish Music. His new book Shul-Going will be published in 2019.