The Artful Times of Andrew Burashko

![]()

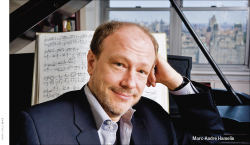

The Art of Time Ensemble has been a fixture on Toronto’s cultural landscape for many years, committed to redefining the experience of music performance and exploring the juxtaposition of high art and popular culture. I’ve long been fascinated by founder and artistic director Andrew Burashko’s programming acumen and his ability to attract a coterie of top-notch musicians to perform with him. Two days before Art of Time’s Sgt. Pepper Canadian Tour began with a concert at the Sony Centre, January 21, I spoke to Burashko on the phone about the origins of Art of Time and Burashko’s own musical training. Perhaps fittingly for a conversation about the Art of Time, our chat proceeded chronologically.

The Art of Time Ensemble has been a fixture on Toronto’s cultural landscape for many years, committed to redefining the experience of music performance and exploring the juxtaposition of high art and popular culture. I’ve long been fascinated by founder and artistic director Andrew Burashko’s programming acumen and his ability to attract a coterie of top-notch musicians to perform with him. Two days before Art of Time’s Sgt. Pepper Canadian Tour began with a concert at the Sony Centre, January 21, I spoke to Burashko on the phone about the origins of Art of Time and Burashko’s own musical training. Perhaps fittingly for a conversation about the Art of Time, our chat proceeded chronologically.

Burashko had a typical classical music training for a serious young piano student. At nine and a half, he began studying with Marina Geringas “the best teacher in the city for young, gifted kids – she produced a lot of professional pianists” – in 1975, about two years after he and his family arrived in Canada from Russia via Israel.

“She gave me an incredible physical foundation,” he says. “I was being groomed to be a concert pianist.” ... His break came when he attracted the attention of Walter Homburger and Andrew Davis. “I was 17; I made my debut with the Toronto Symphony. I performed with them well into my career. I think I did ten seasons with them. Ten different concerti. I was supposed to go to Manhattan School of Music to study with Nina Svetlanova. Because my whole life I was made to practise, I guess I rebelled as I was finishing high school. And I quit music [pause]. So I spent a year at U of T doing sciences and then towards the end of that year, Roman Borys, who was the cellist of the Gryphon Trio, talked me into going to Banff – I hadn’t touched the piano in a year – as a duo. Which I did, to the chamber music program. It was my first time in Banff and there I met a lot of people who are friends to this day. As well as one of my most important mentors, Marek Jablonski.”

While in Banff, he realized that his “heart was in music, but I wanted to do it in my terms.” That meant going to Vancouver to study with Lee Kum-Sing for two years. (One of the people Burashko had met in Banff was Jamie Parker and Parker and his brother Jackie had studied with Lee.) Then Jablonski came to Toronto in 1987 and Burashko followed him to what is now the Glenn Gould School. “Those were the four most formative years of my life,” he said, “because I had at least one lesson a week with Marek and I played every month with Leon Fleisher.”

I reacted positively to Burashko’s comment about his link to Fleisher (I am a great admirer of Fleisher’s work); Burashko responded in kind: “You know, most of my ideas about pianism and interpretation come from Fleisher …. He is incredible. Truly.”

After those four years with Jablonski, Burashko studied with Bella Davidovich in New York for two more. “And things began to happen for me.” He worked with new music groups, chamber music groups like Amici, even toured with the Gryphon Trio before Jamie Parker joined. And taught. Which he considers a crucial part of his life until recently.

Classical music ... I always believed, as I still do, that it was incredibly compelling and exciting and has the potential to speak to anyone if they’re exposed to it just at the right time at the right place in the right way.

Turning points: A key part of the Burashko narrative involves modern dancer Peggy Baker, who returned to Canada from New York in 1991. “Working with her I gained access to a whole other world. The world of the theatre, really. Where things are, for lack of a better word, a helluva lot more theatrical than in a concert hall. Lighting is important. Staging. All those things. And creating a dramatic environment. And also, after all those years I got to know a lot of incredible people like Karen Kain, James Kudelka, Margie Gillis.”

Then comes a surprisingly candid admission: “I guess that, along with the fact that it was a real grind and struggle in the classical music world, I never got to the point where I could dictate my terms. So if ever an orchestra called that I hadn’t worked with before and asked me ‘Do you know, whatever, Rach 2?’ I would say yes. Between travelling and working I was at the piano all the time cramming, some years learning three or four new concerti a year. And it’s no fun playing stuff for the first time, all the time. It’s a huge pressure. Blah-blah-blah-blah. So all those things kind of converged. And the main thing was that I was disheartened by the fact that all the classical audiences were so old and nobody was really doing anything about turning people on to classical music. I always believed, as I still do, that it was incredibly compelling and exciting and has the potential to speak to anyone if they’re exposed to it just at the right time at the right place in the right way. And so that’s how Art of Time began.

“The general idea – I’m oversimplifying – was to create programs which would also include the involvement of either actors or dancers. Because of Peggy I had access to the dance world. I had many friends, still do, who are actors. So actors, dancers, pop musicians, jazz musicians – with the idea that they would hopefully attract their audience and once they were in the theatre then they would be disarmed by the familiar and open to the unfamiliar. And that’s how it began and it’s evolved from there.”

Disarmed by the familiar and open to the unfamiliar. Juxtaposition as the catalyst for gaining and growing an audience. And doing it on his terms.

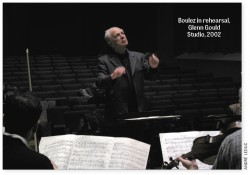

The impetus for his first concert production came from an agent he shared with Scott St. John. St. John was running a series at the time called “Millennium” but he “got sick of doing it.” The agent asked if Burashko would be interested in starting something in its stead. He’d been dreaming of doing something like that for years, even tried to organize similar projects but unable to follow through because of lack of time or know-how. “Even in the first few years of Art of Time, I was so busy with my own career it was completely haphazard. I invested my own money in it. I would write grants. I would just basically have enough money to rent the Glenn Gould Studio three nights a year and present three different chamber music programs. And by then I had really long-standing musical partnerships with Steven Dann and Joel Quarrington and Amanda Forsyth, Pinchas Zukerman. It’s such a small world. I knew all these people, they were my friends, colleagues. And they were excited about doing something new and different. And musicians are always excited or drawn to working with other good musicians.”

The concert he produced in 1998, “a very eclectic program of Russian music – from Glinka to Schnittke,” is one he’s presented frequently since. “It was Stravinsky, Glinka, this big sprawling, cheesy, beautiful kind of bel canto mini-concerto for piano and string quintet, the Schnittke quintet and Prokofiev Overture on Hebrew Themes. And I opened with a Brodsky poem. I’m also a very big fan of Joseph Brodsky. Which was about exile, essentially. And I think that first time I had Ted Dykstra read it. Basically it was music, with a little bit of a twist.”

That “First Season” (1999/2000) consisted of just three one-nighters. “Then for the next few years, I just kept going. There was no infrastructure. I would get on the phone, I would invite people. There was nothing, other than to pay the players and to rent the hall. And that’s how it continued until about 2005. Slowly it was growing, mainly through the arts community. I was becoming more and more daring with the programs and I was just aware that it would never grow if I kept doing it on the sidelines, growing by the seat of my pants, it would never go anywhere.

“In 2005 we moved to Harbourfront and started doing four shows of two-nighters. It was basically, I don’t want to say whim, I went on some sort of belief that wasn’t backed by anything in the physical world. That first year our budget was about $60,000. Today it’s over a million dollars.”

I point out to him that Art of Time is such an evocative name, since the concept of time is so central to what is arguably the core of music. He immediately agrees and expands the thought: “The most noticeable and important fingerprint, for lack of a better word, the most important quality, of a musician or the first thing I notice about a musician, is their sense of time.” But the name also works on another level, he quickly says. And again Leon Fleisher’s name re-enters the conversation.

“Fleisher used to talk about compositions as these elaborate structures or cathedrals built out of time. They were time structures. So on those two levels, really, that’s how I came up with Art of Time.”

2015/2016: Our conversation moves into the three shows that will complete the 2015/2016 season, Zappa, Erwin Schulhoff and Hawksley Workman. “What drew you to Frank Zappa?” I ask. “Wow!” he responds, explaining that Zappa has made a deep impression on him since his teens. Later, in the new music world, he was exposed to him a number of times. (“Zappa’s the only one I could think of who straddled more than one world completely.”) In fact, he says, it was a Zappa concert by Frank Boudreau and the Quebec Contemporary Music Society at the Music Gallery, way back in 1988, that planted the seed for Art of Time’s own Zappa program, February 19 and 20. “Their Zappa show was so much fun. It blew me away.”

2015/2016: Our conversation moves into the three shows that will complete the 2015/2016 season, Zappa, Erwin Schulhoff and Hawksley Workman. “What drew you to Frank Zappa?” I ask. “Wow!” he responds, explaining that Zappa has made a deep impression on him since his teens. Later, in the new music world, he was exposed to him a number of times. (“Zappa’s the only one I could think of who straddled more than one world completely.”) In fact, he says, it was a Zappa concert by Frank Boudreau and the Quebec Contemporary Music Society at the Music Gallery, way back in 1988, that planted the seed for Art of Time’s own Zappa program, February 19 and 20. “Their Zappa show was so much fun. It blew me away.”

That concert never left him; and knowing that the charts for that music existed defined the repertoire for February’s show. Most of the arrangements for the upcoming concert are from the late 1980s and are very dense and busy. Burashko wanted to dilute the “assault-on-the-senses” effect a little bit by adding numbers like Bobby Brown Goes Down and Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow. And Stephen Clarke and Gregory Oh, the two keyboardists in the show (Burashko is conducting), wanted to do Zappa’s four-hands piece, Ruth Is Sleeping (so astonishingly contemporary, it sounds like it could have been written today).

“I’m trying to turn people on to all this music,” Burashko said, explaining his decision not replicate the Boudreau program. “We have such a diverse audience and we’ve developed all this trust just based on previous experience, not necessarily knowing what to expect, so I wanted to add a few of Zappa’s lighter fare tunes.”

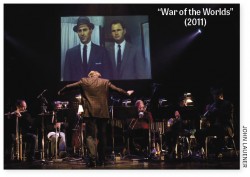

Burashko says that his programming has become increasingly more daring over the years. His “War of the Worlds” program began with a tribute to Bernard Herrmann, who collaborated with Orson Welles on radio, and ended as a theatre piece with a few musicians when Burashko realized that there was very little music (and none by Herrmann) in the original radio broadcast. “I Send You This Cadmium Red” blended Gavin Bryars’ music with John Berger’s words and images. “Magic and Loss: A Tribute to Lou Reed” was, in his words, amazing. “It was seminal in a way, because the essence of Lou Reed is rock ‘n’ roll and simplicity and attitude. To dress it up in fancy clothes would be to just miss the point and destroy the music. I can’t think of anything farther from classical music.”

The current Beatles project, Sgt. Pepper, also crosses no genres. Admitting he’s a Beatles nut, Burashko says that the important thing is to approach the project with great reverence, while retaining the spirit and feel of the original, which is pop music and rock ‘n’ roll. There’s nothing classical about this show other than the involvement of classical musicians (along with the pop musicians) and the classical composers who wrote the arrangements. Sgt. Pepper is far and away Art of Time’s most popular show. It’s been mounted three separate times. And Burashko completed a “great, gruelling” 13-concert, 18-day tour of the show through the Eastern United States in November. A tour of the American midwest is set for September 2016. “That music just connects on such a deep level with people.”

Next, I ask about the Schulhoff show, coming up April 1 and 2. I’m a fan of Schulhoff’s diverse sonic palette, I say. Again Burashko agrees. Schulhoff, he says, was very eclectic; the upcoming concert is a repeat of one Art of Time put on in 2005, with the addition of Martha Burns performing the aptly named Sonata Erotica for female voice solo. Violinist Stephen Sitarski, cellist Thomas Wiebe, flutist Susan Hoeppner and Burashko on the piano all return from the original cast ten years ago, joined by such local superstars as violist Teng Li, alto saxophonist Wallace Halladay and others in Schulhoff’s Hot Sonate for Alto Sax & Piano, Concertino for Viola, Flute & Double Bass, Five Jazz Etudes for Piano and String Sextet.

Burashko wanted to bring it back because “it’s such amazing music” (there’s that word again!). The first time he played any Schulhoff was on a [Robert Aitken-led] New Music Concerts program in 1993, the year Burashko’s daughter was born. “So thanks, Bob,” he says. Besides, Art of Time’s audience has grown exponentially. “In 2005, our audience was one-twentieth of what it is now.” So for many it will be an entirely new show.

Finally in this season, Hawksley Workman will sing Bruce Cockburn’s music in the latest instalment of the Art of Time Songbook, May 13 and 14. This is the first time a songbook has been devoted to the work of a single composer and is the culmination of much back and forth between Burashko and Workman. “I love Hawksley Workman,” Burashko told me, before offering an explanation as to why it took so long for the singer to agree. “He called me; he had seen and heard enough stuff that we did that he really wanted to do something with us.” The general idea for Songbook is to invite a non-classical singer to choose 12 songs they’ve always wanted to do; then Burashko delegates the songs to a group of disparate composers/arrangers to create arrangements for an ensemble that is half pop, and half classical. It’s always a collaboration but he gives the singer licence to be as creative as possible. “It’s about finding that fine line about being as creative as possible without ruining the original intent of the song.” It was Workman’s choice to do Cockburn, and only Cockburn. Burashko will get the charts for the music two months before the show and the concert will be preceded by four full days of intensive rehearsal.

One of Art of Time’s strengths is its impressive roster of musicians. I comment on the alchemy that must have have gone into selecting Christine Duncan and Wallace Halladay for Zappa, and Halladay and Teng Li for Schulhoff, all of whom are making their debut with the ensemble. “The thing that I pride myself on most is the group of musicians, of artists, that I get to work with,” Burashko answered. “Having that incredible luxury of only working with people that I want to. Over the years, that collective has grown to such an extent that I’m proud to say that most musicians would love to work with Art of Time because it also means working with musicians whom they love.

“With Christine – I had heard her a number of times over the years – when I heard these Zappa charts – they’re incredibly complex – and when I heard them in the 80s they were done with two classical singers. It was still a great show and I loved it, but it really ruined something for me. So Christine was a no-brainer because there aren’t that many non-classical singers who are literate enough to learn this music, who are good readers.”

All three remaining shows this season exemplify Burashko’s curatorial prowess: the programs themselves; the chemistry that unites great music and excellent musicians; Art of Time’s transformative theatrical magic.

“It’s so intuitive” Burashko says. “Ultimately I never go near anything that is unfamiliar to me. Programming to me is about creating something balanced with a really interesting arc. And the world is my oyster.”

The Art of Time Ensemble performs Zappa February 19 and 20 at Harbourfront Centre Theatre.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.