On the Edge with Claire Chase

![]()

When Claire Chase speaks there is a sense of urgency in her voice, as if she’s always on the verge of a discovery that she can’t wait to reveal. It’s not exactly an incorrect assumption to make – Chase is famous for being a musician who is always reaching ahead of her time. As flutist/founder of New York’s ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) and an active performer of newly composed works, Chase has always looked towards the future – creating the music that until now has yet to be heard.

When Claire Chase speaks there is a sense of urgency in her voice, as if she’s always on the verge of a discovery that she can’t wait to reveal. It’s not exactly an incorrect assumption to make – Chase is famous for being a musician who is always reaching ahead of her time. As flutist/founder of New York’s ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) and an active performer of newly composed works, Chase has always looked towards the future – creating the music that until now has yet to be heard.

To that end, she’s already accomplished a lot. Praised in The New Yorker as “the young star of the modern flute,” Chase is one of new music’s most relentless advocates. She’s a prolific soloist and recording artist, and a frequent collaborator with composers both established and emerging. She’s a recipient of a 2012 MacArthur “Genius Grant” for her work in visioning an artist-driven business model that emphasizes giving performing musicians the freedom to direct their own career paths. She’s also, incidentally, slotted as a co-artistic director of summer music at the Banff Centre for 2017 – but in the meantime, she comes to Toronto this month as a guest of Soundstreams, for two shows inspired by the musical future of the flute.

Density 2036. The first, “Density 2036,” is part of a 22-year-long centenary celebration in the making. Tracing its roots to the premiere of Edgard Varèse’s solo flute masterwork Density 21.5 in 1936, Chase’s project is a series of annual commissions, leading up to a 24-hour flute recital in the year 2036. Each year she collaborates with a different roster of composers to premiere a recital-length solo set, with the objective of performing all 22 years’ worth of music as a 100th-anniversary celebration of the Varèse original.

On October 4 at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, Chase (along with sound engineer Levy Lorenzo) will open Soundstreams’ new Ear Candy concert series with a selection of music from the last three years of the Density project. The show will sample from a daunting breadth of musical language: two older works – Steve Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint and of course, Varèse’s Density 21.5 – as well as pieces from Density 2036’s three-year archive of commissions, including recent works from Marcos Balter, Mario Diaz de León and Du Yun.

When it comes to Chase’s choice of composer-collaborators, nothing is out of bounds. “The only rule that I’ve given myself for the project is that every time a piece is created through Density, the piece that follows it has to be a complete departure,” she says. “I don’t want to repeat collaborations. I don’t want to repeat language. I want every new Density birth to really be a birth – so in choosing composers, I’m interested in those who are really going far outside their comfort zones…and who are as fiercely and fearlessly committed [as I am] to the idea of creating something new: new for them, new for me, new for the instrument.

“It’s a very difficult thing to ask someone to do,” Chase concedes. “But I love that question. I love the space that it opens up. I love the vulnerability and the malleability that results. So I look for people who are up for that adventure – and who want to jump off that proverbial cliff with me.”

As the soloist leading that cliff-top jump, preparing for an end goal 22 years in the future is no easy task. However, for Chase it is in part this long-term, cumulative nature that gives Density 2036 its appeal. “It’s about the idea of really setting the bar high for myself,” she says. “Of saying, okay, what would it be like to build up to being able to play continuously for 24 hours when I’m 58 years old? It’d be an Olympic sporting event – but it’d have to also be something that really is in service of the music. How could I do that and what would my training look like over these decades? It was such an interesting question that I had to start the project immediately.

“And it’s about saying, okay, the goal is to create this repertory. If I can commit seriously to making it, performing it, and putting it out there for myself, but be just as committed to disseminating it and making sure that it is available for other flutists – for them to study, to learn, to make it their own, to play it better than I can – then that would be really cool.”

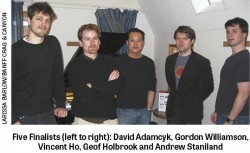

Magic Flutes. Chase’s second Toronto appearance, titled “Magic Flutes,” will open Soundstreams’ mainstage season at Koerner Hall on October 12. At first glance the concert program, which includes works by long-revered composers for the flute like Debussy and Takemitsu, fulfills all the expectations of a standard flute recital. But at Soundstreams – especially with Claire Chase in tow – “standard recitals” are not what they do. A second look reveals that the show will feature five flutists (Chase, joined by Marina Piccinini, Patrick Gallois, Robert Aitken and Leslie Newman) positioned in what Soundstreams bills as a “surround-sound” setup, pairing classic 20th-century flute repertoire with less-known works and a world premiere from local composer Anna Höstman. According to Soundstreams artistic director Lawrence Cherney, the show takes its cue from the tale of the Pied Piper, and harnesses the potential of the flute as “both a force for good, and a force for evil.”

And if Soundstreams plans to reshape what the flute can do – and what it can represent – in this concert, then Chase is game. “What excites me most about the flute,” Chase explains, ”is that it is our oldest musical instrument. Our little tube, our little pipe, was the first musical instrument, other than the voice, and percussion in its earliest iteration. That’s really moving to me, really inspiring to me, and it makes me think about all the ways that this instrument – and the way that we tell stories through it – can still evolve.”

“Ideally, we are getting smarter,” Chase continues, laughing. “Ideally our brains are evolving. And so our instruments and the way that we play them, but most importantly the way that we communicate with them – the new languages we develop through them – we have a responsibility to evolve that as well. And flute is front and centre in that effort, because it was the first.”

A Self-Identified Termite. Of course, musical evolution, at least as Chase describes it, is a multifaceted thing – not only about the music that performers play and how they play it, but about shifting the social structures upon which that music is built, for the better. The work that won Chase her MacArthur fellowship focused on just this. Her own unique brand of musical entrepreneurship – what she calls an “artist-driven organizational model” – is about giving performers the agency to perform with intent, and to direct their own professional development. It’s about seeing the musical artist as a whole person, and strengthening the connective tissue between that person and the spaces around them.

Says Chase: “This model is [about enabling] the artist as a fully empowered agent of the work of her community. That’s something that’s deeply important to me. It’s the reason I formed ICE; it’s also the reason why I am an advocate for many other organizations and ensembles. I just believe deeply in the power of young artists doing for one another what, frankly, institutions are doing a lousy job of doing for us. I think that in some ways that message has been misconstrued to say, ‘oh, we can do this for ourselves, you guys are off the hook!’ That’s not it at all. It’s more of a termites-vs-elephant way of looking at the world. And as a self-identified termite, I believe it’s my duty, and it’s our duty, to help do for one another what is not going to happen with these big cultural gatekeepers.”

And the advice she would give to young artists, who are hoping to do just that?

“My best advice is from Oscar Wilde: that you should ‘be yourself, because everyone else is taken.’ That’s the truest way to say it. It’s not just that being yourself is something we all walk around doing effortlessly. It’s a lifetime of work and it’s a daily slog…it’s also a daily joy, to figure out who we are.

“But being committed to being ourselves and celebrating that, indeed, ‘everyone else is taken,’ is not the path that is encouraged by all institutions, by all teachers…It’s certainly not the path I was encouraged to take. It’s not the reigning conservatory advice. In fact, what we’re taught to do, in many music programs, is exactly the opposite. It’s, ‘how can I make myself more like this mold? How can I follow this path? How can I follow the shine of this person?’ Of course we learn from each other, by repetition and by emulation. But we also learn by noticing, and by feeling, and by trusting ourselves. If there’s one thing that I can do to help a younger generation of flutists and artists trust themselves and trust one another, it would be that.”

It’s clear that she lives by her own advice. The sense of who Chase is as a person is intimately tied to what she does. The sense of her own individuality, her own physicality, permeates her playing, such that audiences can hear in the music her own unique voice. It’s a hopeful thought, that she believes that we all can trust our own paths, our own selves, our own potential shine. And a success story, as well – because that’s what she did, and she is luminous.

Sara Constant is a Toronto-based flutist and musicologist, and is digital media editor at The WholeNote. She can be reached at editorial@thewholenote.com.