Preamble

This longer-than-usual Opener will begin with a coincidence of dates, and then eventually make its way, in a great wobbly orbit, back to where it began.

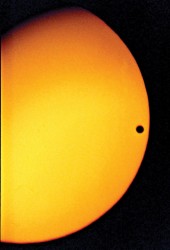

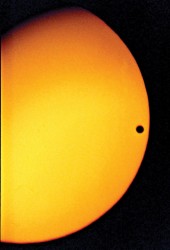

The coincidence (1): June 8 2004 was the last occasion on which, from an earthbound perspective, the planet Venus was observed traversing the face of the star we call our sun. It is a phenomenon known to astronomers as the “transit of Venus,” and it takes place twice in quickish succession (eight years apart) after which it doesn’t happen again for either another 105.5 years, or else another 121.5 years. So the previous two were in December 1874 and December 1882 respectively; and the two following the 2004/2012 pair, will be in December 2117 and December 2125 respectively.

The coincidence (1): June 8 2004 was the last occasion on which, from an earthbound perspective, the planet Venus was observed traversing the face of the star we call our sun. It is a phenomenon known to astronomers as the “transit of Venus,” and it takes place twice in quickish succession (eight years apart) after which it doesn’t happen again for either another 105.5 years, or else another 121.5 years. So the previous two were in December 1874 and December 1882 respectively; and the two following the 2004/2012 pair, will be in December 2117 and December 2125 respectively.

The coincidence (2): June 5 2012 will be the second of the two “transits” in our lifetimes. So for those of us who missed the June 8 2004 transit, you could accurately say the upcoming June 5 transit has become a “once in a lifetime” opportunity. That being said, June 5 2012 will also in all likelihood be the start of rehearsals for the Philip Glass/Robert Wilson opera, Einstein on the Beach, which will kick off Toronto’s sixth annual 10-day Luminato Festival at the Sony Centre three days later (June 8). Einstein on the Beach, while largely composed, Glass says, in New Brunswick, has never been performed in Canada. This too, according to the publicists, will be a “once in a lifetime event.”

Now On With the Story

March 19, 2012, around 10:30pm, Venus was not tickling Apollo’s fiery chin. She was hanging out with some other shining celestial orb, low in the north-western sky, over Pearson airport. The two points of light were so close together that I had to rub my eyes to be sure I wasn’t drunk. Even once I was sure I wasn’t seeing double, I had to stop and wait, to see if the two points of light would resolve into an oncoming or receding airplane, travelling along my line of sight and therefore seeming for a moment to hang, still, in the night sky. But no, there they stayed, side by each, almost touching.

“Look,” I said to my eldest son. “It’s Venus and Jupiter. So close they are almost touching.” (I said it with all the authority fathers muster when there’s no-one around to contradict.) Aforementioned son, however, whipped out his smart phone. “I have a GPS-based app for that,” he said. A few deft wiggles of the app-posable thumbs that I do not possess, and he held the ever-so-clever phone up to the sky. As if by magic, a star map gleamed from its screen, more densely populated with stars than the light-dimmed city night sky behind it, and with the name of each bright star superimposed on the screen. Fascinated, I watched as he turned slowly to the north west to bring “Jupiter and Venus,” as I had proclaimed them to be, into alignment with the cosmos he held in his hands. The authority of fatherhood hung by a thread. “Jupiter and Venus” the smart phone said. Whew.

I pushed my luck. “Lucky the phone uses Roman rather than Scandinavian mythology” I said, “or Fricka would get jealous, and bloody Wagner would go on and on about it.”

“I’m not even going to ask,” he said.

The name John Percy deserves to ring as many bells for readers of this magazine as the name Gustav Holst should for (ear-)budding astrophysicists with iPods. Devotees of Tafelmusik, I daresay, will be more likely than most to already know the name of this University of Toronto Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and Astrophysics. It was John Percy, after all, who mentored Tafelmusik’s The Galileo Project, and subsequently nominated it as Canada’s entry in the International Year of Astronomy’s 2009 Prize for Excellence in Astronomy Education and Public Outreach. Following this, in April 2009, as we diligently reported back then, the International Astronomical Union named a newly observed asteroid after Tafelmusik.

I would have been reminded of John Percy yesterday if he hadn’t already been in my mind. Because yesterday Tafelmusik Media announced the release of The Galileo Project: Music of the Spheres TMK1001DVDCD (1DVD & 1 CD music soundtrack). “Conceived, programmed and scripted by Tafelmusik bassist Alison Mackay,” the release proclaims, “[this] … fully-integrated concert program combines projected high-definition images from the Hubble telescope and Canadian astronomers with music by such composers as Bach, Monteverdi, Rameau, and Handel — performed completely from memory, exploring the fusion of arts, science and culture in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

So as I say, I would have been reminded of John Percy, if I hadn’t had a letter from him, just the other week, about the U of T’s upcoming April 28 symposium on, wait for it, the “forthcoming June 5 transit of Venus at which we shall have Victor Davies give a short presentation about his opera The Transit of Venus. I’m really excited by this linkage of astronomy and music/theatre.”

Winnipeg composer Victor Davies’ opera, The Transit of Venus, was based on a stage play with the same name by Canadian playwright Maureen Hunter (who wrote the libretto for the opera as well). The play was first produced in 1997, the opera ten years later). But the particular transit that is their subject matter was not the 2004 transit, but the 1761/1769 pair — an event in the life of nations as fitting a backdrop for grand opera as any that one could imagine.

It was, after all, the equivalent of the space race, nation pitted against nation, using all the technological resources at their disposal, throwing “the works” into the battle for bragging rights to the precious information about the cosmos, its size and mysteries, that could be gleaned from precisely measuring and triangulating the march of Venus across the face of the sun.

Of course, opera for its purposes requires not only the stars but the star-crossed. In the case of Davies’ and Hunter’s opus, this is “the unfortunate Guillaume Le Gentil, French astronomer,” who, according to Wikipedia, “spent eight years travelling in an attempt to observe either of the transits, [and whose] … unsuccessful journey led to him losing his wife and possessions and being declared dead.”

The symposium on the transit of Venus takes place Saturday April 28, 2012, in Alumni Hall 400 at St. Michael’s College, from 10am to 5pm. The symposium is free and no registration is required.

Other than, perhaps, excerpts from the CBC recording of Davies’ opera during the coffee break, I offer no guarantee of music during the event (although Davies, I hear, will give a short presentation).

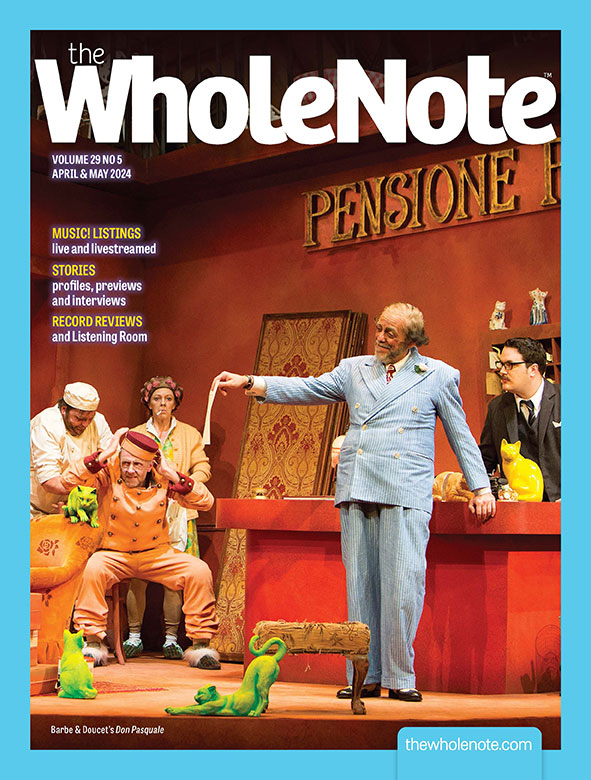

But “opera” which is the focus of this issue, means “the works,” after all. In the case of science, I’d venture to say, that means openness to art, and for art, to science. There’s all kinds of stuff in this issue that reflects this.

So a toast to “the works”: to the sphere of opera, and to the opera of the spheres!

—David Perlman, publisher@thewholenote.com