Watching Mark Murphy slowly weave his way through the Old Mill dining room to the stage, leaning on the arm of a helpful young man, is surely a testament to his own comment, “I’m eighty”. As he was seated carefully on his chair centre-stage with his music stand close by, I felt the wistful sadness of seeing this icon, a survivor of the classic era of jazz and one of a select few who can call themselves an innovator, on the decline. Yet Murphy’s first words to the audience were fully disarming and the opening phrase of ‘What Is This Thing Called Love’ completely erased my uneasiness. His is still the voice we know and love.

Watching Mark Murphy slowly weave his way through the Old Mill dining room to the stage, leaning on the arm of a helpful young man, is surely a testament to his own comment, “I’m eighty”. As he was seated carefully on his chair centre-stage with his music stand close by, I felt the wistful sadness of seeing this icon, a survivor of the classic era of jazz and one of a select few who can call themselves an innovator, on the decline. Yet Murphy’s first words to the audience were fully disarming and the opening phrase of ‘What Is This Thing Called Love’ completely erased my uneasiness. His is still the voice we know and love.

His characteristic tone – the way he almost cries out his notes, how he dips into his lower register then soars effortlessly into his falsetto – is clear and energetic. Age has not diminished his breath control, his ability to hold a straight note or his time feel. He sings with a seemingly careless ease.

His trio of relatively young players supported him flawlessly, consisting of Alex Minasian on piano, and two Canadians, Morgan Moore on bass and Jim Doxas on drums. Doxas’ sensitive style was particularly impressive, with seamless dynamic phrasing and flowing sounds that seem to simply appear.

Murphy is an expert craftsman who squeezes all there is from every syllable of a lyric. And squeeze the lyric he did on his aching performance of another Cole Porter standard, ‘I've Got You Under My Skin’. He introduced Porter as being "the best" and a "consummate composer" because he "controls all parts of the music", referring of course to Porter composing the chords, melody and lyric of each of his songs. While Murphy sang his unorthodox arrangement the room was silent. It was a spacey, tense version of the standard with an almost skeletal accompaniment by Murphy's trio. This spacious style, reminiscent of Shirley Horn with languid back-phrasing, with supremely relaxed, painfully slow tempos and with a nuanced approach to the lyric, was a recurring theme throughout the night.

Other notable ballads included ‘Turn Out The Stars’ (Lees/Evans), half-sung, half-spoken with strong hints of beat poetry, the devastatingly evocative ‘Again’ (Newman/Cochran) and a flirtatious version of ‘Fotografia’ (Jobim) which Murphy reprised later in the night using a different set of lyrics. Stepping up the tempo ever so slightly in George and Ira Gershwin’s ‘Stairway to Paradise’, Murphy demonstrated his uncanny ability of taking an old fashioned lyric and filling it with meaningful, modern feeling. He finds the delicacy of the idea, expressing it in the lighter and darker shades of a life rich in experience.

Well-known for his improvising, Murphy's scatting is both playful and direct at the same time. His somewhat mumbling syllables are really expressions in time, tone and intonation, and remind me of another jazz icon, Betty Carter. Murphy makes no distinction between interpreting a tune and improvising. He sings a little of the head then suddenly strays into his own melodies, throwing in ad lib lyrics and scatting. While performing ‘Stompin' at the Savoy’ at a quick, eyebrow-raising tempo for anyone familiar with the words, he tripped himself up by back-phrasing too far, and losing the lyric. He caught up by scatting a wee bit, and humorously playing the age card. It was charming when he sang, “What is this – I’ve gone to the other song again, haven’t I?” He also touched on and improvised around his own famous lyrics in Oliver Nelson’s tune ‘Stolen Moments’ and Horace Silver’s ‘Senor Blues’.

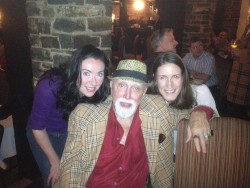

During the break, Murphy sat amongst the audience shaking hands and signing autographs. We were delighted to have a little conversation and a picture with him.

The second set opened with Herbie Hancock’s ‘Maiden Voyage’. An indulgent, elongated ending set the tone for the rest of the show when Murphy interjected “Then suddenly everybody falls out of the boat” and went into an abstract scat. He obviously felt relaxed, with a glass of red and white on the go and sharing stories like the one about Tallulah Bankhead’s papier de toilette.

For his final song Murphy recalled the mood of longing and loss created in the movie Brokeback Mountain, then proceeded to perform a heartbreaking rendition of ‘Too Late Now’ (Lerner/Lane). It became clear that Murphy had masterfully created a mood of his own that evening, indulgent and tantalizing. After the warm welcome of the first set, we were treated to a tiny glimpse into his personality. At any moment he could plunge us into a new emotion, or surprise us with a pleasantly mischievous comment.

Murphy hadn't performed in Toronto in thirty years until this appearance October 1 at the Old Mill as part of the JAZZ.FM 91.1 Sound of Jazz Concert Series. He brought with him an expertise that could only be acquired from his impressive career which, at this point, spans six decades. He is currently working on a new recording with New York City vocalist Amy London, and his next Canadian dates are November 20 & 21, 2012 at the Jack Kerouac Festival in Quebec City.