Bach To The Future!

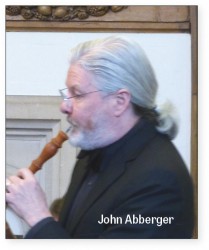

Funny how new initiatives that should be big news have a way of sneaking up on you. Case in point, apparently there’s a Bach festival (three concerts) happening in town next month and nobody told me! Titled “Four Centuries of Bach. First Annual Toronto Bach Festival” it appears to be the brainchild of John Abberger, who besides being a principal oboist for Tafelmusik and the American Bach Soloists, recorded an album of Bach organ concertos for Analekta in 2006 as well as an album of Bach’s Orchestral Suites 2 and 4 in 2011. His principal accomplice appears to be Phillip Fournier, organist at the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, on King St. W. Fournier will doubtless dazzle the audience May 28, in the middle concert of the three, performing Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in d BWV 565 and other works on the Oratory’s historically inspired Gober and Kney instrument.

Funny how new initiatives that should be big news have a way of sneaking up on you. Case in point, apparently there’s a Bach festival (three concerts) happening in town next month and nobody told me! Titled “Four Centuries of Bach. First Annual Toronto Bach Festival” it appears to be the brainchild of John Abberger, who besides being a principal oboist for Tafelmusik and the American Bach Soloists, recorded an album of Bach organ concertos for Analekta in 2006 as well as an album of Bach’s Orchestral Suites 2 and 4 in 2011. His principal accomplice appears to be Phillip Fournier, organist at the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, on King St. W. Fournier will doubtless dazzle the audience May 28, in the middle concert of the three, performing Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in d BWV 565 and other works on the Oratory’s historically inspired Gober and Kney instrument.

The other two concerts, bookending this one, May 27 and May 29 take place at St. Barnabas Anglican Church, 361 Danforth Ave and are, I suspect, Abberger’s “babies.” The first is a concert that includes two of Bach’s Weimar cantatas (Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen and Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben), with a vocal lineup featuring Ellen McAteer, soprano, Daniel Taylor, alto, and Lawrence Wiliford! Info for the Sunday closing concert is somewhat vaguer – sonatas and trios by J.S. Bach, played by “Musicians of Four Centuries of Bach.” But if the calibre of the players in the first two concerts is anything to go by, we’re in for a three-part treat!

Given that the scope of the project is fairly ambitious, the people responsible really should devote more time to publicity. To wit, their website lists only concert titles, venues and dates, and a chance to order tickets. And that’s pretty much it. You may see some concert programs if they update the website by the time you read this, but it doesn’t look like they will. So being somewhat diligent about these things, and wishing always to provide a service to my readership, I did a little sleuthing and managed to uncover a few details, with which I can make some conclusions about this little-known upstart of a music festival.

Which leads me directly to my second reason for exhorting you to catch this Bach festival while you can, which is that the organizers seem to be burying their light so deep beneath a bushel - lack of publicity, last-minute organization - that “Four Centuries of Bach” might end up being how long it takes Abberger et al to get through Bach’s catalogue of compositions for at least (wait for it) four centuries.

Grumbles aside, Abberger has enough experience with Bach’s cantatas and other works to be able to craft a better-than-average performance. And Fournier is a gifted musician: I’ve enjoyed listening to him play a Bach sonata or two on at least one occasion.

Calling anything a “First Annual” festival is equal parts hubris and hopefulness. May the latter prevail!

Toronto Masque Theatre: If you’re looking for a good show to see this month, you need not make any decisions based on trust, either of the abilities of the musicians on stage or of the conjecture of any music critics, look no further than Toronto Masque Theatre’s performance of Purcell’s The Fairy Queen, which will be given at the company’s new digs at the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto, May 27 to 29 at 8pm. TMT was conceived with the idea of doing English 17th-entury repertoire, for which Purcell fits the bill perfectly, and the work will be staged and danced to by the redoubtable Marie-Nathalie Lacoursière, who has chosen to spice things up by setting the story contemporaneously. This is the kind of show that TMT was created to do, with singers, dancers and musicians who will do it very well. If you feel like something operatic, this concert is a sure win.

Monteverdi: If you’re not in the mood for English opera, consider attending a performance of one the masterworks of one of the greatest composers of the 17th century, performed by the ensemble in the city that’s most qualified to do it. I’m speaking of course about Toronto Consort’s final concert of the season, a complete performance of Claudio Monteverdi’s Vespro della beata Vergine, which they’ll be doing at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, May 6 to 8. I can’t tell you the number of times that other groups’ recordings and performances of this particular work have left me disappointed in the past, particularly with the oft-repeated decision to perform the Vespers a cappella, and I’m happy to say that the Consort will not be duplicating this particular faux pas. They’ll be bolstered by a Montreal-based consort of sackbuts, La Rose des Vents, and that implies that some continuo will also be on hand – entirely necessary for a major work that was performed in a positively palatial church in one of the richest cities of the Renaissance. English tenor Charles Daniels will also lead the group, so you can bet the Consort is going to end this season on a high note.

Tafel’s Two-City Tale: Of course, all these picks lead up to the Toronto early music scene’s safest bet this month. Tafelmusik will be performing another program designed by Alison Mackay, this one based around the coffee-house scene of the early 18th century. “Tales of Two Cities: The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee-House” brings Canada’s number-one baroque orchestra together with oud player Demetri Petsalakis, percussionist Naghmeh Farahmand and singer Maryem Tollar in a concert of Arabic music along with the music – if the Leipzig connection is any indication – of J.S. Bach. It seems like there’s something in this concert for everyone. Not interested in hearing just another Tafelmusik Bach concert? The Arabic angle adds an interesting perspective. Not particularly keen on world music? Tafelmusik does a good enough job of Bach. You can catch this cultural cross-pollination at Koerner Hall, May 19 to 22, and George Weston Recital Hall, May 24.

Windermere Fan: And finally, there’s a lesser-known group in town that deserves to be gambled on. The Windermere String Quartet is a string ensemble that features some interesting repertoire and is capable of a very spirited performance indeed. Their next show, on Sunday, May 15, will feature a couple of standards of the string quartet repertoire, namely a Haydn quartet and Schubert’s Death and the Maiden. But the WSQ has also found a hitherto-unknown composer, the early 19th-century Spaniard, Juan Chrisóstomo Arriaga, who died at the tender age of 20. The WSQ has a following already, puts on a fun show, and is willing to explore the entire length and breadth of the quartet repertoire. They’re worth a shot.

Windermere Fan: And finally, there’s a lesser-known group in town that deserves to be gambled on. The Windermere String Quartet is a string ensemble that features some interesting repertoire and is capable of a very spirited performance indeed. Their next show, on Sunday, May 15, will feature a couple of standards of the string quartet repertoire, namely a Haydn quartet and Schubert’s Death and the Maiden. But the WSQ has also found a hitherto-unknown composer, the early 19th-century Spaniard, Juan Chrisóstomo Arriaga, who died at the tender age of 20. The WSQ has a following already, puts on a fun show, and is willing to explore the entire length and breadth of the quartet repertoire. They’re worth a shot.

David Podgorski is a Toronto-based harpsichordist, music teacher and a founding member of Rezonance. He can be contacted at earlymusic@thewholenote.com.