Living with Legends (or, How to Build a Program)

Time is an equal opportunity employer” – Denis Waitley

While time may provide equal opportunity to those now living, history can be much less kind to the legacies of those who have gone before us. For example, when reviewing composers of classical music, we see specific instances of how such artists are grouped into seemingly infinite pyramid-shaped hierarchies, their status as “genius” determined as much by the quality of their output as their enduring and perennial appeal. Starting at the top, we encounter the universally revered composers, the capital-G Geniuses: Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, Bach, and the other craftsmen whose works have transcended time and transfixed audiences for centuries. These are the figures after whom busts are sculpted and monuments built, and who can be trusted to draw large audiences year after year.

Another tier of the legacy tower is that of the well-respected, yet under-performed composer. Arnold Schoenberg and subsequent proponents of the Second Viennese School belong here, as do many of the 20th century’s finest musical minds, such as Ligeti, Berio and Stockhausen. While their works might not tickle the ears of every person who happens upon them, or fill up a concert hall, they nonetheless played significant roles in the development of new forms of musical expression. Yet another category is that of composers who achieve renown by virtue of their writing for a specific instrument, such as Josef Rheinberger’s compositions for the organ or Franz Liszt’s piano works; while both of these examples wrote a wide variety of material for a range of vocal and instrumental forces, their legacies rest primarily on a specific segment of their output.

No matter how we categorize the characters in our history books, these theoretical organizational principles are just that – theoretical. From a practical perspective, how does one choose which of these compositional strata to draw from when deciding what to perform next week, month, or year? Balance is key when constructing a concert program, and finding a stimulating and satisfying blend of composers and repertoire is the challenge of artistic directors across the globe. A quick case in point: when Pierre Boulez assumed control of the New York Philharmonic in 1971, succeeding Leonard Bernstein, his attempts to incorporate higher volumes of contemporary music led to much criticism and a drop in annual subscriptions to the orchestra’s seasons. While there was great merit to Boulez’s contemporary crusade, the slight change in emphasis from the easily digestible, top-tier “Genius” to the more sinewy Schoenbergian genius did not resonate with his audience and led to a challenging tenure for one of the 20th century’s greatest composer-conductors.

Much like the categorization of composers, there is a near-infinite number of approaches that can be taken to program-building and we will encounter some of them in this column, exploring a variety of early music through numerous combinations and juxtapositions, both of the music itself and the people who wrote it.

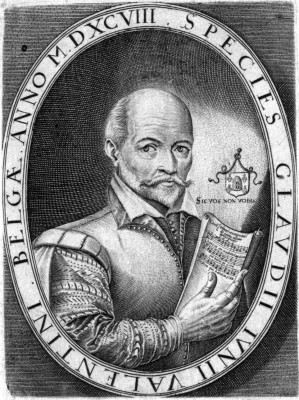

Discovering Antonio Lotti

A relatively unknown figure in a scene dominated by such heavyweights as Claudio Monteverdi, Antonio Vivaldi and Domenico Scarlatti, Antonio Lotti was an Italian composer who spent his career at St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, working his way up the musical hierarchy from singer to maestro di cappella. Lotti wrote in a variety of forms, producing masses, cantatas, madrigals, nearly 30 operas, and instrumental music, thereby influencing some of the era’s great geniuses: Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel and Jan Dismas Zelenka owned copies of Lotti’s Missa Sapientiae, consisting of a Kyrie and Gloria scored for chorus and orchestra, transcribed from the manuscript by each in their own hand.

This connection between Lotti’s Missa Sapientiae and the music of Bach, Handel and Zelenka is made apparent in Tafelmusik’s “Lotti Revealed”, presented from November 14 to 17 and directed by Ivars Taurins. This is the first time Tafelmusik has performed music by Lotti and it will be paired with excerpts from Bach and Zelenka masses, as well as Handel’s Carmelite Vespers. Sumptuous and expressive, Lotti’s music will prove a valuable addition to Tafelmusik’s repertory and stimulating listening for those who enjoy the richness and depth of late-Baroque music.

This Sounds Familiar…

The turning back of our clocks signals more than the arrival of colder temperatures; it also commences the annual transition to Christmas music, which regularly features combinations of classic works and interesting revelations. On November 24, the York University Concert and Chamber Choirs join forces to present a seasonal selection of music by Dieterich Buxtehude, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, and Camille Saint-Saëns. Two of these composers are famous largely for their organ works: Buxtehude for his masterful praeludia, chorale preludes and pieces in free style; Saint-Saëns for his Third Symphony, which gives the organ a prominent place in what is an overall glorious masterpiece. Pergolesi, meanwhile, is renowned for his Stabat Mater, a passiontide classic that makes multiple appearances each year. While the names may be familiar, the York University choirs will not be performing a greatest hits concert, but rather a series of pieces that focuses on various aspects of the Christmas story.

Saint-Saëns’ Oratorio de Noël is a cantata-oratorio hybrid written for soloists, chorus, organ, strings and harp, composed while he was an organist at La Madeleine in Paris. Distinctly French in harmonic language, yet clearly indebted to the form of the Baroque cantata and dramatic element of the oratorio, this work combines arias, recitatives and chorus movements with the Latin texts of the Catholic lectionary, creating a piece of music with distinct characteristics and fascinating form. The cantata theme continues with Buxtehude’s Das neugeborne Kindelein, a Protestant church cantata for chorus and chamber orchestra, and Pergolesi’s Magnificat. These works will not only frame Saint-Saëns’ unconventional cantata with more traditional essays in the form, but delight the audience with infrequently performed works by renowned masters of their craft.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos are stunning masterpieces, as virtuosic a display of compositional prowess as their instrumental interpreters must be to convey the secrets contained therein. This November, the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin visits Kingston on November 26 and Koerner Hall on November 27 in a performance of the first five Brandenburgs, a not-to-be-missed musical event. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin (Akamus for short), founded in East Berlin in 1982, is one of the world’s leading chamber orchestras on period instruments. It has established itself as one of the pillars of Berlin’s cultural scene, holding its own concert series at the Konzerthaus Berlin for more than 30 years, as well as a concert series at Munich’s Prinzregententheater. Having sold more than one million CDs, their highly successful recordings have won all important awards for classical recordings; with such extraordinary international performers making a rare Canadian appearance, tickets for these concerts will certainly be in high demand.

Now in its 18th season, the Ottawa Bach Choir (OBC) continues to impress with their high level of skill and devotion to the art of their namesake composer. As a testament to their dedication and continued excellence, the OBC has been invited to return to Leipzig for the 2020 Bachfest as one of a select number of ensembles worldwide to present Bach’s entire chorale cantata cycle, a remarkable and imposing proposition! On November 30, the Ottawa Bach Choir, led by founding artistic director Lisette Canton, will visit Toronto for A Bach Christmas, providing us with the opportunity to hear a miniature Bachfest of our own. This program includes the cantatas the choir will perform at Bachfest Leipzig 2020 (Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht, BWV124; Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid, BWV3; Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh allzeit, BWV111), as well as the Christmas interpolations from the Magnificat, BWV243 (Vom Himmel hoch, Freut euch und jubiliert, Gloria in excelsis Deo, Virga Jesse floruit), the celebratory motet, Singet dem Herrn, BWV225, and more. Featuring the Ensemble Caprice baroque orchestra with strings, oboes d’amore, horn, as well as soprano Meredith Hall, countertenor Nicholas Burns, tenor Philippe Gagné and bass Andrew Mahon, there is little doubt that this concert will give Bach aficionados much to rejoice about this Christmas season.

Now in its 18th season, the Ottawa Bach Choir (OBC) continues to impress with their high level of skill and devotion to the art of their namesake composer. As a testament to their dedication and continued excellence, the OBC has been invited to return to Leipzig for the 2020 Bachfest as one of a select number of ensembles worldwide to present Bach’s entire chorale cantata cycle, a remarkable and imposing proposition! On November 30, the Ottawa Bach Choir, led by founding artistic director Lisette Canton, will visit Toronto for A Bach Christmas, providing us with the opportunity to hear a miniature Bachfest of our own. This program includes the cantatas the choir will perform at Bachfest Leipzig 2020 (Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht, BWV124; Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid, BWV3; Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh allzeit, BWV111), as well as the Christmas interpolations from the Magnificat, BWV243 (Vom Himmel hoch, Freut euch und jubiliert, Gloria in excelsis Deo, Virga Jesse floruit), the celebratory motet, Singet dem Herrn, BWV225, and more. Featuring the Ensemble Caprice baroque orchestra with strings, oboes d’amore, horn, as well as soprano Meredith Hall, countertenor Nicholas Burns, tenor Philippe Gagné and bass Andrew Mahon, there is little doubt that this concert will give Bach aficionados much to rejoice about this Christmas season.

Whether discovering the profundity of Antonio Lotti for the first time, hearing a rare performance of Saint-Saëns’ Oratorio de Noël, or basking in the resplendent genius of Bach, the month of November is full of magnificent music that is well worth the price of admission. There is also much to look forward to in the following weeks, as the ushering in of the Christmas season brings with it many more opportunities to take in landmark works by both renowned and less-known composers. See you in December – until then, feel free to get in touch at earlymusic@thewholenote.com.

EARLY MUSIC QUICK PICKS

NOV 19, 7:30 PM: University of Toronto Faculty of Music. Early Music Concerts: Purcell’s King Arthur. Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre. Containing some of Purcell’s most lyrical music and adventurous harmonies, King Arthur is a mystical journey through Arthur’s battle against the Saxons, with cameo appearances by Cupid, Venus and more! Much like last month’s Acis and Galatea, this is a fine opportunity to hear the U of T’s rising stars.

NOV 23, 7:30PM; NOV 24, 3PM: Cantemus Singers. “A Boy is Born.” Church of the Holy Trinity, 19 Trinity Square (Saturday)/St. Aidan’s Anglican Church, 70 Silver Birch Avenue (Sunday). In a column devoted to building a program, Cantemus deserves a special mention, as their concerts regularly consist of a fascinating variety of material. This month’s presentation features carols and motets from Renaissance England, including Thomas Tallis’ stunning Missa Puer natus est nobis for seven voices.

NOV 24, 7PM: Cantorei Sine Nomine. Bach: Christmas Oratorio. St. Paul’s Anglican Church (Uxbridge), 59 Toronto Street South. And so, it begins! This season’s first performance of the Christmas Oratorio features six cantatas drawn from the larger work, one of the finest Christmas choral pieces ever written and an unbroken sequence of drama and beauty that continues to inspire audiences, despite being premiered almost three centuries ago.

DEC 4, 7PM; DEC 5 TO 7, 8PM; DEC 8, 3:30PM: Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra. “O Come, Shepherds.” Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre. With a diverse program connected through an underlying pastoral theme, this concert promises a unique combination of Baroque Christmas concertos and the soulful folk music of Southern Italy, with its own rhythms, instruments, and spirit – a fine continuation of Tafelmusik’s mission to broaden its horizons and those of its listeners, through innovative and unexpected presentations.

Matthew Whitfield is a Toronto-based harpsichordist and organist.