"I Call myself Princess" Digs Deep

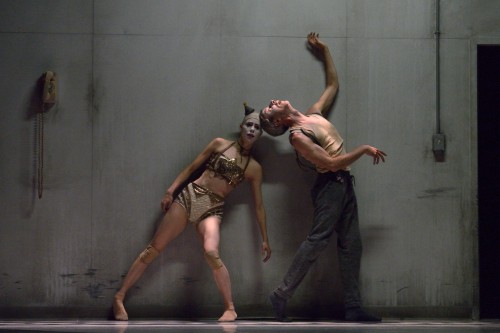

The September 2018/19 music theatre season starts off with the exciting world premiere of a new piece by Jani Lauzon, which will be presented in a three-way co-production by Paper Canoe Projects, Cahoots Theatre Projects and Native Earth Performing Arts at Native Earth’s Aki Studio. I Call myself Princess (the lowercase of the “m” in “myself” is intentional) is a fascinating new “play with opera” that uses an interdisciplinary approach to delve into the past, making new discoveries about both the past and the present by relating it to today.

A hundred years ago in 1918, an opera titled Shanewis (The Robin Woman) with music by Charles Wakefield Cadman and libretto by Nelle Richmond Eberhart made its debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, as part of a three-part program about American life. It was such a success that it returned the next season and continued to tour and be revived around the United States for years afterwards.

A hundred years ago in 1918, an opera titled Shanewis (The Robin Woman) with music by Charles Wakefield Cadman and libretto by Nelle Richmond Eberhart made its debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, as part of a three-part program about American life. It was such a success that it returned the next season and continued to tour and be revived around the United States for years afterwards.

This was the second opera by Cadman and Eberhart on an “American Indian” theme, but their first to be accepted for production. What seemed to make the difference with Shanewis was the contribution to the story and libretto by Cadman’s musical touring partner the Creek/Cherokee singer Tsianina Redfeather, who, although never officially credited, provided ideas from her own life and experiences – resulting in an opera that resonated with both producers and audiences.

A hundred years later, playwright Jani Lauzon’s I Call myself Princess is about to bring this story back to life for us in a modern context. The first seeds of inspiration for the play came when the playwright was working with the Turtle Gals Performance Ensemble, the acclaimed Native Women’s collective that she co-founded with Michelle St. John and Monique Mojica. While working on a new project, Lauzon came across the 1972 book The Only Good Indian: The Hollywood Gospel. It was full of critical viewpoints on the inclusion, or lack thereof, of Indigenous performers in opera, jazz, silent film, the talkies and vaudeville, starting at the turn of the 20th century.

“At first we were surprised by how many Indigenous performers there were. Then we were upset with ourselves that we were surprised,” Lauzon tells me. “We had bought into the narrative that we weren’t there. But we were there. We were producers, writers, performers.” The story of Tsianina and the opera Shanewis in particular stood out as something to be explored further. “What struck me about Tsianina Redfeather was her working relationship with Charles Wakefield Cadman,” she says, “and the complexities of how they were both navigating the industry and expectations of the audience.”

Cadman was already well known at the time as a composer and expert in “American Indian Music” and for composing his own pieces in a style that became known as “Indianist.” He gave lecture tours around the United States and Europe, joined from 1908 by Redfeather, who dressed for the concerts in beaded traditional costumes, her hair in braids, and was credited as “Princess Tsianina.”

In I Call myself Princess, we meet Tsianina and Cadman as they and their opera are discovered by William, a young Métis opera singer in the course of his studies. As he learns more and deals with the difficulties of finding his own identity as a young Indigenous performer in the world of opera and today’s political climate, music and theatre become intertwined. “I was conscious of the need to seamlessly integrate the libretto and music that was Charles Wakefield Cadman’s and Nelle Eberharts’ within the context of my story,” says Lauzon. “In many ways the writing process was a constant reminder that the very act of reconciliation is a delicate balance that takes work, thought and negotiation.”

This intertwining of story, genre, time and theme is exciting and ambitious. Joining Lauzon to undertake the challenge of bringing it all to life is director and dramaturge Marjorie Chan, also artistic director of Cahoots, a theatre company dedicated to working with diverse artistic voices. Many things, Chan says, drew her to the project: knowing Jani Lauzon and her work with the Turtle Gals, the chance to tell a story that has thus far had little opportunity to be heard, but also the combination of theatre with opera. Chan herself is well known as an opera librettist. “When we started to work on this project,” she says, “I often felt like my worlds were starting to come together.”

This intertwining of story, genre, time and theme is exciting and ambitious. Joining Lauzon to undertake the challenge of bringing it all to life is director and dramaturge Marjorie Chan, also artistic director of Cahoots, a theatre company dedicated to working with diverse artistic voices. Many things, Chan says, drew her to the project: knowing Jani Lauzon and her work with the Turtle Gals, the chance to tell a story that has thus far had little opportunity to be heard, but also the combination of theatre with opera. Chan herself is well known as an opera librettist. “When we started to work on this project,” she says, “I often felt like my worlds were starting to come together.”

When I asked Chan about the intermixture of play and opera, she said that to her it is like an opera within a play. “In terms of the actual opera that was performed on the Met stage in 1918, we are, in the play, looking at its creation from both the time when it was created and from our modern perspective in 2018,” she explains. “We are poking at it from all different sides and different times so that pieces of the opera are consistently being performed throughout the entire evening.”

One of the challenges of getting this right is casting, particularly with the very specific demands for each character. Acclaimed for her warm strong mezzo-soprano voice and experience in contemporary opera, Marion Newman, of Kwagiulth and Stó:lo First Nations as well as English, Irish and Scottish heritage, was an obvious choice for Tsianina, Chan says. Newman has been an integral part of the project since the workshop in 2014. Opposite her, as the composer Charles Wakefield Cadman, is versatile performer and director Richard Greenblatt, known, perhaps most famously, for his two-man show with Ted Dykstra, Two Pianos Four Hands. As Cadman he not only has an acting role but a musician’s role: playing the piano – in character – throughout the piece.

One of the challenges of getting this right is casting, particularly with the very specific demands for each character. Acclaimed for her warm strong mezzo-soprano voice and experience in contemporary opera, Marion Newman, of Kwagiulth and Stó:lo First Nations as well as English, Irish and Scottish heritage, was an obvious choice for Tsianina, Chan says. Newman has been an integral part of the project since the workshop in 2014. Opposite her, as the composer Charles Wakefield Cadman, is versatile performer and director Richard Greenblatt, known, perhaps most famously, for his two-man show with Ted Dykstra, Two Pianos Four Hands. As Cadman he not only has an acting role but a musician’s role: playing the piano – in character – throughout the piece.

Playing William, the Métis opera student, is Aaron M. Wells (of Ehattesaht and Lax Kwalaams First Nations) from the west coast, who, Chan says, is not only a terrific singer but also “understands on a really intuitive level William’s position as an Indigenous person in a program that was not specifically designed with his culture in mind.”

Leading the musical side of the production is music director Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate whose background, classical training and compositional experience make him – as Lauzon says – a perfect fit for the show. A Chikasaw classical composer and pianist whose own works are inspired by Indigenous history and culture, Impichchaachaaha’ Tate met Jani Lauzon when he came to Toronto in 1994 to compose the music for Native Earth’s production of Diva Ojibway. While “blown away by his talent and experience as a composer,” Lauzon says, “it is also a blessing that Jerod is well versed in Cadman’s music, the Indianist music and Tsianina. He gets the way Indigenous people work and think because he is one, and he understands the circumstances that Tsianina faces because as an Indigenous artist he lives it every day.”

The music he will be directing is made up of key moments from the opera, from a beautiful aria about love to an idealized version of an Ojibwe song that Cadman included not only in the opera but also in the “Indian Lecture” tour that he and Tisanina took all over the world. As well, Lauzon says, “Jerod is composing a traditional Ojibwe melody that grows as a musical theme throughout, and Marion Newman has been hard at work practising the slide guitar, which Tsianina played for the troops overseas during World War One.”

As Chan says, since in the play William is discovering the opera Shanewis, “We have to dive in. We have to hear enough of the original to understand and ask, ‘How do I feel about that?’”

The company is also spending time exploring what might have been the original performance style for opera in 1918, adds Chan: “How well that (might) hold in our contemporary space and seeing where we should offer something more naturalistic that we might be more accustomed to, and to be more truthful to the piece.” The opera was daring for its time, as Chan emphasizes. “It has a female protagonist who is very strong, very forthright. Furthermore, she is a female protagonist who is an Indian who speaks quite truthfully about her experience as a colonized person. She is the love interest of a white man and rejects him in favour of honouring her people. So we think about how that would have landed on an audience of 1918.”

As Lauzon mentioned, the opera – though highly successful in its time – contains images and concepts that today would be recognized as problematic. A challenge for the creative team and company will be balancing this intriguing and daring 1918 world with the more familiar world of 2018, and focusing the play in performance so that the audience will receive it in the way the playwright intends.

Chan says that Lauzon is “gifted in layering all these complex ideas in a really articulated, clear way.” According to Chan, the play is about Tsianina Redfeather at the turn of the century but “it is also about this young Métis man in an opera program, and what it means for him to encounter and be impacted by this music. That’s the beauty of how we find the ways to leak the music in and take it out, to stay with the emotional journey of the young Métis opera singer.”

Intriguingly, when I suggest that there was a time travel element to be experienced, Chan says that they are aiming for something even more complex: “the thought that if we might expand what we know around us we could reach it; that they are existing at the same time.”

Ultimately, says Chan, the goal of the team is that “the audience should be able to come in and experience the journey of a young man reaching back into his culture – and reclaiming culture and music that belongs to him.”

I Call myself Princess plays September 9 to 30, at Native Earth Performing Arts’ Aki Studio, Toronto.

MUSIC THEATRE QUICK PICKS

SEP 28 & 29, 7:30PM: Sound of the Beast. Theatre Passe Muraille (followed by a national tour): Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, who collaborated so wonderfully with Tapestry Opera last season on the Persian inspired Tap Ex: Forbidden, is the solo artist here as emcee “Belladonna the Blest,” and, using a combination of hip-hop, spoken word and storytelling, tells truth to power with a brutally honest take on policing in Black communities.

SEP 28 & 29, 7:30PM: Sound of the Beast. Theatre Passe Muraille (followed by a national tour): Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, who collaborated so wonderfully with Tapestry Opera last season on the Persian inspired Tap Ex: Forbidden, is the solo artist here as emcee “Belladonna the Blest,” and, using a combination of hip-hop, spoken word and storytelling, tells truth to power with a brutally honest take on policing in Black communities.

SEP 18 to 29: Grand Theatre. Prom Queen: The Musical. The High School Project - Grand Theatre London, 471 Richmond St., London. The Grand Theatre’s annual high school project aroused controversy earlier this year in the city of London because it tells the true story of Marc Hall, who in 2002 wanted to take his boyfriend to the school prom. Originally developed at Sheridan’s Canadian Musical Theatre Project, the show has earned rave reviews elsewhere and here will have a large cast of real high school students, 50 onstage and 30 backstage.

SEP 13 to OCT 7: Musical Stage Company. Dr. Silver: A Celebration of Life. Heliconian Hall, 35 Hazelton Ave., Toronto. The latest creation by the talented Johnson sisters, Britta and Anika, this co-production with Mitchell Cushman’s Outside the March company promises to be “immersive” and very different from your usual musical. At the historic, tiny, Heliconian Hall in Yorkville.

Toronto-based “lifelong theatre person” Jennifer (Jenny) Parr works as a director, fight director, stage manager and coach, and is equally crazy about movies and musicals.