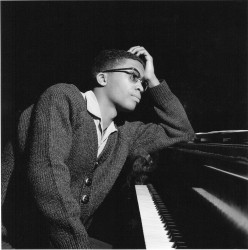

Remembering Ian Bargh

This month’s article is a bit more serious than most of my contributions. The year began with the loss of a friend when Ian Bargh died on January 1. And with him went a treasure trove of musical know-how, a knowledge of the great standard song repertoire, including rarities that hardly anyone else knew, and the ability to interpret them, turning them into musical gems.

This month’s article is a bit more serious than most of my contributions. The year began with the loss of a friend when Ian Bargh died on January 1. And with him went a treasure trove of musical know-how, a knowledge of the great standard song repertoire, including rarities that hardly anyone else knew, and the ability to interpret them, turning them into musical gems.

He also had that most desirable of qualities in a jazz musician: a sound of his own, a personal stamp that he put on everything he played.

A Scot and, like myself, born in Ayrshire, Ian in many ways was typical of the breed: careful with money, hard working, a bit of a rough diamond, but under it all, generous and sentimental.

In the last few years he and I talked quite often about death and we always agreed that we would not want a lingering end to life. Well, the end did come quickly for Ian. We came home at the beginning of last December from a cruise on which my band, the Echoes Of Swing, was playing. Ian, as they say, played his buns off and the smile on his face told us all just how much he was enjoying himself.

A month later and he was gone from us, but not in spirit, for a part of him will always be there for those of us who knew him, and his music will live on through his recordings.

Like the rest of us, Ian did have his idiosyncrasies and he certainly could have his grumpy moments when he saw the world through dark coloured glasses. I remember one occasion when, for a joke, I gave him a bottle of Famous Grouse scotch whisky. Somehow it seemed more appropriate than a sweet sherry!

I mentioned that Ian had “a sound.”

No single musical element identifies jazz musicians more than their personal sound — a sound that represents the individual. In the arts, a personal identity is something that any artist should strive for whether it be in the visual arts, literature, theatre or, of course, music. In jazz, Armstrong, Bechet, Lester Young, Bud Freeman, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Jack Teagarden, Pee Wee Russell and “Red” Allen are only a few who had a personal sound that makes them instantly recognizable.

The American composer, author, historian and musician, Gunther Schuller, had this to say on the subject: “It is up to the individual to create his sound, if it is within his creative capacities to do so — one that will best serve his musical concepts and style. In any case, in jazz, the sound, timbre, and sonority are much more at the service of individual self-expression, interlocked intimately with articulation, phrasing, tonguing, slurring, and other such stylistic modifiers and definers.”

In simpler terms, be your own person.

The late veteran trumpet player Sweets Edison also had his views on the subject when speaking about the early jazz greats. In his opinion, most of the musicians in those days were artists. They were individualists and had a sound of their own. If Billie Holiday sang on a record you’d know it was nobody but Billie. Louis Armstrong could hit one note on a record, and you’d know it was Louis Armstrong. Nobody sounded like Lester Young, like Coleman Hawkins, like Bunny Berigan, like Benny Goodman, Chu Berry, Dizzy Gillespie. They all had a recognizable sound.

More recently, Gary Smulyan, winner of the Downbeat critics’ poll in 2009 and 2011 for baritone sax, said that sound comes before everything ... If you listen to just the tenor saxophone — John Coltrane, Johnny Griffin, Joe Lovano, Chris Potter, Don Byas, Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins — they all play tenor saxophone but you know who they are immediately. And to Gary, that’s the defining thing. “I’ve given a lot of thought and a lot of practice to try to really develop a sound that’s personal and unique to me” he says. “I mean you could be a great technician but if you don’t have a good sound no one’s going to want to hear you … And it’s really the identifying characteristic of who you are as a musician. And your sound is not in the instrument … The sound is something that you carry within your very being and that’s what comes out. So take someone like Sonny Rollins. I think that if you gave Sonny Rollins 50 different tenor saxes, 50 different reeds and 50 different ligatures, he’s going to sound like Sonny Rollins, with some variation because maybe the instruments aren’t comfortable … But essentially what’s going to come out is Sonny Rollins … and I tell that to my students. I say, ‘Don’t look for the magic instrument, because there’s no magic instrument.’”

I don’t mean to suggest that one should slavishly imitate one musician. As the saying goes, when you copy from one person that’s plagiarism, but if you copy from everybody it’s called research and every jazz musician is a product of what he or she has listened to and absorbed. Some musicians say they get ideas about their sound from players who don’t even play the same instrument as they do. It’s more about concept, phrasing and note choices.

It’s the same magic that makes a melody stick in our head, and the same magic that makes a particular improvised solo a classic.

And that takes us back to Ian Bargh and the very elusive personal touch he brought to his music.

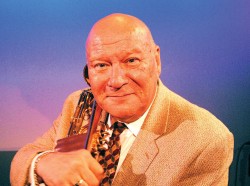

Finally, if we look ahead to the beginning of next month, on March 7 at 5:30pm in the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, one of our great Canadian musicians who has the magic in his music will be performing. His name? Guido Basso. He, along with another master musician, Don Thompson, will present a free concert of jazz classics and originals. If you are lucky enough to be there you will hear what the words in this month’s column have tried to describe.

Meanwhile, happy listening and try to make some of it live music.

Jim Galloway is a saxophonist, band leader and former artistic director of Toronto Downtown Jazz. He can be contacted at jazznotes@thewholenote.com.