Francis Poulenc – Intégrales des mélodies pour voix et piano

Francis Poulenc – Intégrales des mélodies pour voix et piano

Pascale Beaudin; Julie Fuchs;

Hélène Guilmette; Julie Boulianne;

Marc Boucher; François Le Roux;

Olivier Godin

ATMA ADC2 2688 (5 CDs)

In his booklet notes for this collection of Poulenc’s mélodies and chansons, baritone François Le Roux describes Poulenc’s music as “a mixture of melancholy and joie de vivre, of solemnity and fun.” As the Canadian Opera Company’s stunning production of Dialogues of the Carmelites last season made clear, Poulenc’s music is not to be taken lightly. Underlying even his most playful works — and there are plenty of those here–is a deeply felt reflectiveness. That’s precisely what the musicians involved in this recording convey so well, and what makes this collection so enjoyable.

Poulenc always claimed that it was the poets whose words he was setting that directly shaped his music. With so many poets involved, it’s no wonder there is such variety in these 170 songs. There are three songs which have never been recorded, some rarities, including a few songs that Poulenc dropped from Le bestiare, and a song cycle for chamber orchestra accompaniment, Quatre poèmes de Max Jacob, that pianist Olivier Godin has transcribed for piano. But what sets this recording apart is that it is the first complete collection of the songs for voice and piano to feature francophone musicians, four from Canada and two from France. This turns out to be revelatory. It’s not just because they all sound so natural and idiomatic. The enunciation of each singer is so clear and unmannered that you can make out every word.

Poulenc loved the music of Maurice Chevalier, and with Les chemins de l’amour he steps into Chevalier’s music hall. He conjures up a delectable waltz for Anouilh’s bittersweet ode to paths not taken. Soprano Pascale Beaudin uses a wonderfully nuanced palette of colours to create a jaunty mood and, at the same time, bring out the undercurrents of longing and regret.

Soprano Julie Fuchs balances the shifting moods of a robust ballad with the touching innocence of a prayer in “La Petite Servante,” one of the Cinq poèmes de Max Jacob. Vocalise shows how expressive Poulenc can be without any text at all, especially with soprano Hélène Guilmette imaginatively fashioning a tragicomic scenario of operatic proportions. Mezzo Julie Boulianne deftly contrasts the despair of Montparnasse, Poulenc’s wartime ode to Paris’ once-vibrant artists’ quarter, with the wryness of Hyde Park in Deux mélodies de Guillaume Apollinaire. Baritone Marc Boucher brings moving lyricism to the nine songs of Tel jour telle nuit (Such a Day Such a Night). His voice seems to grow darker and more urgent as day turns into night in Éluard’s cycle of poems.

In his prime, François Le Roux was a peerless interpreter of art songs from his native France. Here he is no longer in his prime. His voice is brittle, underpowered and weathered around the edges. But that doesn’t affect my pleasure in his singing on this set. He’s always interesting, never bland. There’s a lifetime’s experience in the way he embraces the nostalgic mood of “Hôtel” from Apollinaire’s Banalités, his top notes resonating with tenderness. You can smell the Gauloises (unfiltered, of course) as he sings, “I don’t want to work, I want to smoke.”

Poulenc was himself a marvellous pianist, and he demands a lot from a pianist in his songs. Olivier Godin makes an especially responsive partner. His finely calibrated sense of momentum and evocative textures animate passages like the exquisite pulsing coda that ends Tel Jour Telle Nuit. Booklet notes and bios are in French and English, but the French song-texts are not, unfortunately, translated.

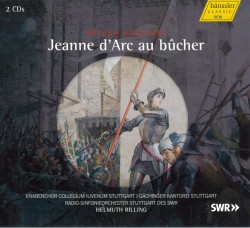

Honegger – Jeanne d’Arc au bucher

Honegger – Jeanne d’Arc au bucher