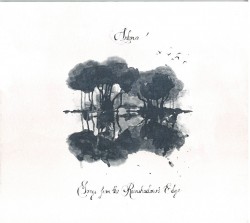

Songs from the Rainshadow’s Edge – a song cycle by Benton Roark - Arkora

Songs from the Rainshadow’s Edge – a song cycle by Benton Roark

Songs from the Rainshadow’s Edge – a song cycle by Benton Roark

Arkora

Redshift Records TK444 (redshiftmusic.org)

Anyone who has lived in Vancouver will be familiar with the term “rainshadow” which, in turn, conveys the elusiveness of sunshine. This lends a rather dreamy, mystical aura to the area and the rainshadow’s edge mirrors that same misty, shimmering border between contrasting states of the psyche. Scored for soprano, flute, viola, bass, electric guitar, percussion and narrator, drawing on texts by Huxley, Carroll, Eckhart, Sartre and composer Benton Roark, the multi-layered five-part song cycle takes the listener on a Jungian journey beyond the edge and back again.

The composer, who based the work on his recollection of a state of depersonalization after a series of crises, did well in selecting the ensemble to perform it. Arkora, a self-described new music collective dedicated to contemporary vocal chamber music in its many forms and led by soprano Kathleen Allan, clearly possesses the fluidity to skillfully evoke the surreal experience of “loss of self” and the struggle between inner and outer realities. Allan’s purity of vocal tone is perfection in its adaptations through the ever-changing mix of genres and mysterious landscape of instrumental timbre.