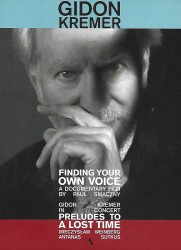

Finding Your Own Voice - Gidon Kremer

Finding Your Own Voice

Finding Your Own Voice

Gidon Kremer

Accentus Music ACC20414 (naxosdirect.com)

In the September WholeNote, Terry Robbins reviewed the CD of Gidon Kremer’s recording of the late Polish composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s 24 Preludes to a Lost Time, Op. 100. Written for solo cello, Kremer plays his own transcription for solo violin. Robbins concluded that “His superb performance befits such a towering achievement, one which is a monumental addition to the solo violin repertoire.”

Accentus Music has since issued a DVD of that unique performance and we now see Kremer spotlit alone on the dark stage in the Gogol Centre in Moscow. Behind him in the darkness is a theatre-size, rear-projection screen on which, at appropriate times, are seen original images from the 1960s taken by photographer Antanas Sutkus. Each selected photograph illuminates the mood of the particular prelude being played, often stark, sometimes sad, sometimes amusing but so appropriate. Genius.

The documentary, Finding Your own Voice, is a film by Paul Smaczny that is a totally engrossing biography of Kremer and his world of music. It revolves about music that embraces Kremer’s life and we hear and see him with musicians including conductors and composers whose music touches him. Listen in as he discusses passages in rehearsals with the likes of Arvo Pärt and others. There are so many thought-provoking observations and philosophical reflections that one may be immediately prompted to watch it again in case you missed something. Whether or not you are a Kremer fan, you will get a lot out of this unusual and illuminating film.