A well-known improviser once stated that “My roots are in my record collection” and most serious fans cite seminal discs that helped them define their commitment to favoured music. That’s why the reissuing of musical classics is so important, especially with improvised music so related to in-the-moment communication. Not only does listening to these innovative discs confirm the fond memories of those who heard them when first issued, but they also provide valuable insights for those hearing them for the first time.

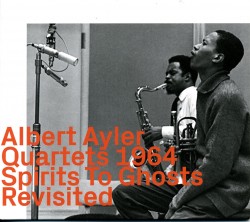

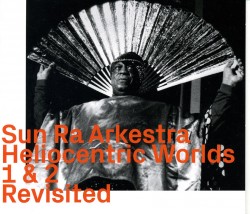

For instance, Albert Ayler Quartets 1964 Spirits to Ghosts Revisited (ezz-thetics 1101 hathut.com) and Sun Ra Arkestra’s Heliocentric Worlds 1 & 2 Revisited (ezz-thetics 1103 hathut.com) are newly remastered versions of discs that helped define the free jazz revolution of the mid-1960s. Moreover the sets are each made up of two LPs initially issued on ESP-Disk. Fifty-six years on, tenor saxophonist Ayler’s basic melodies swirled out in rasping, ragged blasts can still be upsetting when first heard. Especially with tunes that begin with sonic excess and climb upwards from there, the saxophonist seems to be repeatedly thrashing out similar elementary themes over and over. Yet these versions of some of Ayler’s best-known tunes are unique in that his foil in both cases is a trumpeter, the little-known Norman Howard on the first four tracks and Don Cherry, famous for his association with Ornette Coleman, on the rest. With Howard’s flighty obbligatos decisively contrasting with Ayler’s wide snarls, they pair perfectly. Sunny Murray’s drum smacks make Holy Holy and Witches and Devils the standout tracks, especially during those times when the saxophonist’s Ur-R&B screams are actually pitched higher than the trumpeter’s clarion growls. Always ready to default into favourite motifs, Ayler works in the melody from Ghosts, his best-known composition, during the first track, and following a thumping bass solo, even layers a mellow turn into his solo on the second. Still, the performances were conventional enough to include recapped heads at the end of each tune. Cherry, on the other hand, brings advanced harmonies to his six tunes, with his soaring brassiness contrasting Ayler’s rugged slurs on the first titled version of Ghosts. At the same time, while the trumpeter sticks to fluttering song-like variations, Ayler uses glossolalia and split tones to deconstruct the tune still further, aided by plucks deviations and col legno pops from bassist Gary Peacock. This contradiction is also obvious on Mothers, the closest to a ballad track in this set. While bowed bass backs Cherry adding operatic highs to his otherwise moderato solo, buzzing strings fill in the spaces alongside Ayler’s sardonic peeps and squeaky altissimo shakes when he takes over the lead. As well, the concluding Children may start off stately and neutral, but after Murray’s door-knocking smacks and echoing double bass thumps quicken the rhythm, both horn men create an explosion of brassy brays and skyrocketing saxophone slurs.

For instance, Albert Ayler Quartets 1964 Spirits to Ghosts Revisited (ezz-thetics 1101 hathut.com) and Sun Ra Arkestra’s Heliocentric Worlds 1 & 2 Revisited (ezz-thetics 1103 hathut.com) are newly remastered versions of discs that helped define the free jazz revolution of the mid-1960s. Moreover the sets are each made up of two LPs initially issued on ESP-Disk. Fifty-six years on, tenor saxophonist Ayler’s basic melodies swirled out in rasping, ragged blasts can still be upsetting when first heard. Especially with tunes that begin with sonic excess and climb upwards from there, the saxophonist seems to be repeatedly thrashing out similar elementary themes over and over. Yet these versions of some of Ayler’s best-known tunes are unique in that his foil in both cases is a trumpeter, the little-known Norman Howard on the first four tracks and Don Cherry, famous for his association with Ornette Coleman, on the rest. With Howard’s flighty obbligatos decisively contrasting with Ayler’s wide snarls, they pair perfectly. Sunny Murray’s drum smacks make Holy Holy and Witches and Devils the standout tracks, especially during those times when the saxophonist’s Ur-R&B screams are actually pitched higher than the trumpeter’s clarion growls. Always ready to default into favourite motifs, Ayler works in the melody from Ghosts, his best-known composition, during the first track, and following a thumping bass solo, even layers a mellow turn into his solo on the second. Still, the performances were conventional enough to include recapped heads at the end of each tune. Cherry, on the other hand, brings advanced harmonies to his six tunes, with his soaring brassiness contrasting Ayler’s rugged slurs on the first titled version of Ghosts. At the same time, while the trumpeter sticks to fluttering song-like variations, Ayler uses glossolalia and split tones to deconstruct the tune still further, aided by plucks deviations and col legno pops from bassist Gary Peacock. This contradiction is also obvious on Mothers, the closest to a ballad track in this set. While bowed bass backs Cherry adding operatic highs to his otherwise moderato solo, buzzing strings fill in the spaces alongside Ayler’s sardonic peeps and squeaky altissimo shakes when he takes over the lead. As well, the concluding Children may start off stately and neutral, but after Murray’s door-knocking smacks and echoing double bass thumps quicken the rhythm, both horn men create an explosion of brassy brays and skyrocketing saxophone slurs.

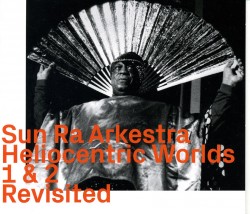

Ayler drowned himself at 34 in 1970, after only eight years of recording, but Sun Ra, who claimed to have been born on the planet Saturn, passed from this planet in 1993 at probably 80 earth years. However, he recorded with various versions of his Arkestra from 1956 on, and with the band still functioning today innumerable discs are available. Heliocentric Worlds from 1965 is particularly noteworthy though, because these were the first LPs massively distributed and which firmly situated Ra in the centre of the improvisational avant-garde. Earlier and later recordings subsequently proved that these exploratory excursions were just one part of his burgeoning oeuvre though. Listening to the suite that takes up the first seven tracks, then and now easily refutes those who claimed the New Thing was no more than random, inchoate noise. Ra’s complex program is as adroitly orchestrated as any symphony with meticulous shading and balance among bass clarinet slurs, piccolo trills, multiple percussion bangs and split-tone showdowns between trumpet and piccolo and sliding alto saxophone and plunger trombone. Massed explosions from the five woodwind players are often followed by col legno emphasis from bassist Ronnie Boykins. When Ra finally asserts himself on Other Worlds, his witty alternation between roadhouse-style piano exuberance and electronic space sizzles underlines the composition’s duality. Jimhmi Johnson’s tympani resonations match the higher-pitched brass throughout, at the same time as five other musicians add clanking claves and small percussion fillips alongside Ra’s relaxed comping and Boykins’ ambulating line. If the penultimate Nebulae highlights free-form blowing from saxophonists, then the concluding Dancing in the Sun could be a Swing Era trope with vamping section work pushed ahead by John Gilmore’s tenor saxophone, Marshall Allen’s alto and a showy Cozy Cole-like drum solo from Johnson. This musical intricacy is confirmed on the subsequent tracks that were Heliocentric Worlds 2. With the Arkestra shrunk to an octet, arrangements emphasize ear worms such as Allen’s piccolo shrills, what sounds like electrified saxophone runs, and the constant leitmotif of Ra’s tuned bongos. Cosmic Chaos confirms its post-modernism as Boykins’ rhythmic swing contrasts with Allen’s multiphonic reed smears, and Robert Cummings’ bass clarinet puffs are as prominent as heraldic calls from trumpeter Walter Miller. Meanwhile Ra’s percussive output is as much Albert Ammons as Cecil Taylor. Finally, the supplementary percussion complete the composition, with gong resonation and bongo-thwacks. However The Sun Myth, a nearly 18-minute concerto defines Ra’s skills even more. Sonorous and contrapuntal, mournful bowed strings are heard at one point and clashing junkeroo-style percussion at another. After the bagpipe-like multiphonic tremolo created by the four reed players presages the finale, Ra’s piano solo with its echoes of Blue Rondo à la Turk confirms the band’s subtle swing groove.

Ayler drowned himself at 34 in 1970, after only eight years of recording, but Sun Ra, who claimed to have been born on the planet Saturn, passed from this planet in 1993 at probably 80 earth years. However, he recorded with various versions of his Arkestra from 1956 on, and with the band still functioning today innumerable discs are available. Heliocentric Worlds from 1965 is particularly noteworthy though, because these were the first LPs massively distributed and which firmly situated Ra in the centre of the improvisational avant-garde. Earlier and later recordings subsequently proved that these exploratory excursions were just one part of his burgeoning oeuvre though. Listening to the suite that takes up the first seven tracks, then and now easily refutes those who claimed the New Thing was no more than random, inchoate noise. Ra’s complex program is as adroitly orchestrated as any symphony with meticulous shading and balance among bass clarinet slurs, piccolo trills, multiple percussion bangs and split-tone showdowns between trumpet and piccolo and sliding alto saxophone and plunger trombone. Massed explosions from the five woodwind players are often followed by col legno emphasis from bassist Ronnie Boykins. When Ra finally asserts himself on Other Worlds, his witty alternation between roadhouse-style piano exuberance and electronic space sizzles underlines the composition’s duality. Jimhmi Johnson’s tympani resonations match the higher-pitched brass throughout, at the same time as five other musicians add clanking claves and small percussion fillips alongside Ra’s relaxed comping and Boykins’ ambulating line. If the penultimate Nebulae highlights free-form blowing from saxophonists, then the concluding Dancing in the Sun could be a Swing Era trope with vamping section work pushed ahead by John Gilmore’s tenor saxophone, Marshall Allen’s alto and a showy Cozy Cole-like drum solo from Johnson. This musical intricacy is confirmed on the subsequent tracks that were Heliocentric Worlds 2. With the Arkestra shrunk to an octet, arrangements emphasize ear worms such as Allen’s piccolo shrills, what sounds like electrified saxophone runs, and the constant leitmotif of Ra’s tuned bongos. Cosmic Chaos confirms its post-modernism as Boykins’ rhythmic swing contrasts with Allen’s multiphonic reed smears, and Robert Cummings’ bass clarinet puffs are as prominent as heraldic calls from trumpeter Walter Miller. Meanwhile Ra’s percussive output is as much Albert Ammons as Cecil Taylor. Finally, the supplementary percussion complete the composition, with gong resonation and bongo-thwacks. However The Sun Myth, a nearly 18-minute concerto defines Ra’s skills even more. Sonorous and contrapuntal, mournful bowed strings are heard at one point and clashing junkeroo-style percussion at another. After the bagpipe-like multiphonic tremolo created by the four reed players presages the finale, Ra’s piano solo with its echoes of Blue Rondo à la Turk confirms the band’s subtle swing groove.

If swing’s the thing, what about the New Acoustic Swing Duo’s sardonically titled eponymous session (Corbett vs Dempsey CD 0066 corbettvsdempsey.com)? With Willem Breuker playing five different woodwinds and Han Bennink a music store’s inventory of percussion instruments, it was the first issue on the ICP label and one of the sessions that confirmed that European improvisers had the same inspirational skills as their North American counterparts. Now New Acoustic Swing Duo is a two-CD set that includes not only the Amsterdam duo’s original 1967 LP, but six newly discovered 1968 live tracks from Essen. Later known for his leadership of the more precise large Kollektief, Breuker (1944-2010) was at his loosest here, squeezing, slurring, shrieking and snarling in free form from all his horns. Bennink, who would soon become a linchpin of the ICP Orchestra, was at his loud ferocious best as well. Constantly in motion, he mixes primordial yelps and cries as he crashes cymbals, beats hand drums, sets snares and toms reverberating, rings bells, smacks and rattles small idiophones and creates undulating tabla drones. The saxophonist puffs out nephritic gut spilling without a real blues line on Singing the Impalpable Blues, moves between squawks and sensitivity on Music for John Tchicai and fires so many broken tones at the percussionist on Mr. M. A. De R. in A. that Bennink’s stentorian responses would enliven an entire street parade. At 21 minutes plus however, the aptly named Gamut is the novella to earlier musical short stories. Working up from overblowing with wrenching vigour, the tenor saxophonist craftily settles on multiphonic slurs and glossolalia to push his ideas, as the drummer pounds along on anything that shakes, Despite snuffling bass clarinet asides at midpoint, Bennink’s relentless bangs and pops bring back altissimo smears, reed bites and sighing flutter tonguing to cement drum bombast and reed explorations into a multi-hued exposition. Interestingly enough, the extended Essen 3 finds Breuker augmenting his reed lines to penny-whistle-like airiness in double motif variation, with the antithesis low-pitched bass clarinet solemnity, while Bennink’s percussion discussion references jazz-swing. Furthermore the fife-and-drum band groove both reach on that track is given more expression on the final Essen 6. As the cacophony of duck-like quacks and air-raid siren shrills from the reedist and drum bangs and slaps give way to a more serene middle section, the concluding bouncy parade sounds find Breuker emphasizing the tongue-in-cheek melody burlesquing he would perfect with the Kollektief, while Bennink’s drum strategy sticks to the jazz affiliations emphasized by the ICP Orchestra.

If swing’s the thing, what about the New Acoustic Swing Duo’s sardonically titled eponymous session (Corbett vs Dempsey CD 0066 corbettvsdempsey.com)? With Willem Breuker playing five different woodwinds and Han Bennink a music store’s inventory of percussion instruments, it was the first issue on the ICP label and one of the sessions that confirmed that European improvisers had the same inspirational skills as their North American counterparts. Now New Acoustic Swing Duo is a two-CD set that includes not only the Amsterdam duo’s original 1967 LP, but six newly discovered 1968 live tracks from Essen. Later known for his leadership of the more precise large Kollektief, Breuker (1944-2010) was at his loosest here, squeezing, slurring, shrieking and snarling in free form from all his horns. Bennink, who would soon become a linchpin of the ICP Orchestra, was at his loud ferocious best as well. Constantly in motion, he mixes primordial yelps and cries as he crashes cymbals, beats hand drums, sets snares and toms reverberating, rings bells, smacks and rattles small idiophones and creates undulating tabla drones. The saxophonist puffs out nephritic gut spilling without a real blues line on Singing the Impalpable Blues, moves between squawks and sensitivity on Music for John Tchicai and fires so many broken tones at the percussionist on Mr. M. A. De R. in A. that Bennink’s stentorian responses would enliven an entire street parade. At 21 minutes plus however, the aptly named Gamut is the novella to earlier musical short stories. Working up from overblowing with wrenching vigour, the tenor saxophonist craftily settles on multiphonic slurs and glossolalia to push his ideas, as the drummer pounds along on anything that shakes, Despite snuffling bass clarinet asides at midpoint, Bennink’s relentless bangs and pops bring back altissimo smears, reed bites and sighing flutter tonguing to cement drum bombast and reed explorations into a multi-hued exposition. Interestingly enough, the extended Essen 3 finds Breuker augmenting his reed lines to penny-whistle-like airiness in double motif variation, with the antithesis low-pitched bass clarinet solemnity, while Bennink’s percussion discussion references jazz-swing. Furthermore the fife-and-drum band groove both reach on that track is given more expression on the final Essen 6. As the cacophony of duck-like quacks and air-raid siren shrills from the reedist and drum bangs and slaps give way to a more serene middle section, the concluding bouncy parade sounds find Breuker emphasizing the tongue-in-cheek melody burlesquing he would perfect with the Kollektief, while Bennink’s drum strategy sticks to the jazz affiliations emphasized by the ICP Orchestra.

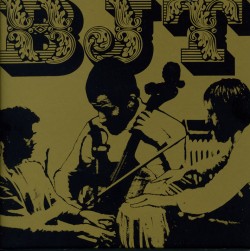

On the other hand Baroque Jazz Trio + Orientasie/Largo (SouffleContinu Records FFLCD057 soufflecontinurecords.com) from 1970, is a session that could only have been created at that time. That’s because the eight selections take on influences from so-called classical and world music, rock and ethnic sounds. Furthermore the members of the Paris-based trio are cellist Jean-Charles Capon, who often plucks his instrument to create guitar-like fills and drummer Philippe Combelle, who spends much of his time on tablas. Since then both have stuck pretty close to the mainstream jazz and instrumental pop music worlds. However the third member is harpsichordist Georges Alexandre, the alias of pianist Georges Rabol, who besides being a notated music recitalist, also composes for ballet, theatre, film, radio and TV. While as with most artifacts of the psychedelic era there are some groovy soundtrack-like suggestions, when Capon’s pseudo lead-guitar stabs, Combelle’s back beat and harpsichord clashes sway together, the references are more towards Led Zeppelin and The Doors and avant-rock freakouts than anything else. Adding tabla interludes and connecting keyboard harmonies, this leaning is most obvious on Delhi Daily and Latin Baroque. However the real demonstrations of the combo’s versatility are Cesar Go Back Home and Largo. The former, a pseudo-blues prodded by cello thumps and harpsichord strums, interpolates a funk beat compete with shuffle rhythms from the drummer. Less slow and dignified than vibrating and swinging Largo is one of the few experiments of this kind that achieves a so-called classical/free-form/rhythmic meld, especially when cello shakes and rolling percussion link up with swift keyboard continuo.

On the other hand Baroque Jazz Trio + Orientasie/Largo (SouffleContinu Records FFLCD057 soufflecontinurecords.com) from 1970, is a session that could only have been created at that time. That’s because the eight selections take on influences from so-called classical and world music, rock and ethnic sounds. Furthermore the members of the Paris-based trio are cellist Jean-Charles Capon, who often plucks his instrument to create guitar-like fills and drummer Philippe Combelle, who spends much of his time on tablas. Since then both have stuck pretty close to the mainstream jazz and instrumental pop music worlds. However the third member is harpsichordist Georges Alexandre, the alias of pianist Georges Rabol, who besides being a notated music recitalist, also composes for ballet, theatre, film, radio and TV. While as with most artifacts of the psychedelic era there are some groovy soundtrack-like suggestions, when Capon’s pseudo lead-guitar stabs, Combelle’s back beat and harpsichord clashes sway together, the references are more towards Led Zeppelin and The Doors and avant-rock freakouts than anything else. Adding tabla interludes and connecting keyboard harmonies, this leaning is most obvious on Delhi Daily and Latin Baroque. However the real demonstrations of the combo’s versatility are Cesar Go Back Home and Largo. The former, a pseudo-blues prodded by cello thumps and harpsichord strums, interpolates a funk beat compete with shuffle rhythms from the drummer. Less slow and dignified than vibrating and swinging Largo is one of the few experiments of this kind that achieves a so-called classical/free-form/rhythmic meld, especially when cello shakes and rolling percussion link up with swift keyboard continuo.

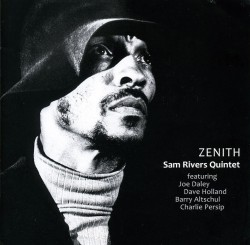

Along with these sets there’s another category that involves sessions recorded years ago, but not issued until now. Prominent among them is Zenith (NoBusiness Records NBCD 124 nobusinessrecords.com), a 1977 date featuring a quintet led by multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers that made no other discs in this configuration. Intense from beginning to end, the one-track, over 53-minute session gives Rivers ample space to display his seesawing style on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano. The uncommon backing band consists of Joe Daley’s tuba lines which often function as a Greek chorus to Rivers’ inventions; the subtle and supple string strategies of bassist Dave Holland; and the boiling tumult provided by not one, but two drummers: Barry Altschul and Charlie Persip. With the bassist’s sympathetic strums framing him, Rivers’ tenor saxophone moves through split tones and glossolalia during the piece’s introductory ebb and flow. Yet, as Daley’s plunger whinnies stunningly contrast with Rivers’ staccato snarls and doits, the sliding narrative picks up additional power from Holland’s walking pumps and hand-clapping drum beats that owe as much to bebop as free jazz. Intricate chording from the bassist with a banjo-like twang, help slow down the pace, which moves to another sequence propelled by Rivers’ low pitched flute modulations, stretching out his passionate storytelling until layered contributions from all five lead to a climax of unmatched intensity. Following heightened applause, Rivers resumes the performance hammering and tinkling tremolo pushes from the piano, followed by supple tongue-stretching slides from Daley, as drum fills and double bass swipes replicate a pseudo-Latin beat. Finally, high-pitched soprano saxophone vibrations, doubled by klaxon-like snarls from the brass player, signal the approaching finale, which despite a detour into a drum dialogue, ends with bass thumps and flutter tongued reed variations that relate back to the initial theme.

Along with these sets there’s another category that involves sessions recorded years ago, but not issued until now. Prominent among them is Zenith (NoBusiness Records NBCD 124 nobusinessrecords.com), a 1977 date featuring a quintet led by multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers that made no other discs in this configuration. Intense from beginning to end, the one-track, over 53-minute session gives Rivers ample space to display his seesawing style on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano. The uncommon backing band consists of Joe Daley’s tuba lines which often function as a Greek chorus to Rivers’ inventions; the subtle and supple string strategies of bassist Dave Holland; and the boiling tumult provided by not one, but two drummers: Barry Altschul and Charlie Persip. With the bassist’s sympathetic strums framing him, Rivers’ tenor saxophone moves through split tones and glossolalia during the piece’s introductory ebb and flow. Yet, as Daley’s plunger whinnies stunningly contrast with Rivers’ staccato snarls and doits, the sliding narrative picks up additional power from Holland’s walking pumps and hand-clapping drum beats that owe as much to bebop as free jazz. Intricate chording from the bassist with a banjo-like twang, help slow down the pace, which moves to another sequence propelled by Rivers’ low pitched flute modulations, stretching out his passionate storytelling until layered contributions from all five lead to a climax of unmatched intensity. Following heightened applause, Rivers resumes the performance hammering and tinkling tremolo pushes from the piano, followed by supple tongue-stretching slides from Daley, as drum fills and double bass swipes replicate a pseudo-Latin beat. Finally, high-pitched soprano saxophone vibrations, doubled by klaxon-like snarls from the brass player, signal the approaching finale, which despite a detour into a drum dialogue, ends with bass thumps and flutter tongued reed variations that relate back to the initial theme.

Whether well distributed or formerly a secret shared only by the cognoscenti, each of these free jazz classics deserve the wider appreciation they can now receive.

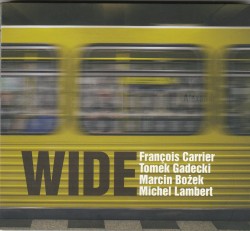

Wide

Wide