Reissues of recorded music serve a variety of functions. Allowing us to experience sounds from the past is just one of them. More crucially, and this is especially important in terms of Free Jazz and Free Music, it restores to circulation sounds that were overlooked and/or spottily distributed on first appearance. Listening to those projects now not only provides an alternate view of musical history, but in many cases also provides a fuller understanding of music’s past.

Little noticed in North America at the time of its 1977 release, Tetterettet (Corbett vs. Dempsey CvsD CD 060 corbettvsdempsey.com) by the Amsterdam-based ICP Tentet was a confirmation of the high quality improvised music gaining prominence in Europe. Listening to the 11 selections played by such subsequently renowned players as pianist Misha Mengelberg and drummer Han Bennink from the Netherlands plus saxophonist John Tchicai of Denmark and Germany’s Peter Brötzmann, the high level of musicianship stands out as well as the freedom composers had to inject broad or subtle humour into the tracks – a concept shied away from by deadly serious experimenters on this side of the Atlantic. Two of the emblematic tracks are Alexander’s Marschbefehl and Ludwig’s Blue Note. On the latter, Mengelberg cycles through an assemblage of properly inflected keyboard motifs from so-called classical music while around him the band, following the energetic lead of one of the saxophonists double-times a pseudo-tango. On the foot-tapping Alexander’s Marschbefehl a march-time variant is subverted with peeping and blaring horn parts as well as a clattering percussion display from Bennink, while the pianist provides pseudo-impressionism with one hand and honky-tonk inflections from the other. As much fun as these and other tracks are, the disc’s showpiece is Mengelberg’s five-part title suite. Managing to encompass echoes of Middle-European salon sounds, Latin dance rhythms and pure improvisation, the sequences encompass outer-space-like tweaks from Michael Waisvisz’s electronics, plunger spills from Bert Koppelaar’s trombone, fierce or furtive split tones from the four saxophonists and Bennink’s ruffs, rebounds and rattles while hitting every part of his kit to ratchet up excitement But the theme, which speeds up and descends in sections, maintains a steady pace due to Alan Silva’s bass holding the beat. As the reed players’ striated vibrations mock their earlier excesses and the drummer turns the beat around, surgically inserted keyboard clicks create a finale that references the introduction.

Little noticed in North America at the time of its 1977 release, Tetterettet (Corbett vs. Dempsey CvsD CD 060 corbettvsdempsey.com) by the Amsterdam-based ICP Tentet was a confirmation of the high quality improvised music gaining prominence in Europe. Listening to the 11 selections played by such subsequently renowned players as pianist Misha Mengelberg and drummer Han Bennink from the Netherlands plus saxophonist John Tchicai of Denmark and Germany’s Peter Brötzmann, the high level of musicianship stands out as well as the freedom composers had to inject broad or subtle humour into the tracks – a concept shied away from by deadly serious experimenters on this side of the Atlantic. Two of the emblematic tracks are Alexander’s Marschbefehl and Ludwig’s Blue Note. On the latter, Mengelberg cycles through an assemblage of properly inflected keyboard motifs from so-called classical music while around him the band, following the energetic lead of one of the saxophonists double-times a pseudo-tango. On the foot-tapping Alexander’s Marschbefehl a march-time variant is subverted with peeping and blaring horn parts as well as a clattering percussion display from Bennink, while the pianist provides pseudo-impressionism with one hand and honky-tonk inflections from the other. As much fun as these and other tracks are, the disc’s showpiece is Mengelberg’s five-part title suite. Managing to encompass echoes of Middle-European salon sounds, Latin dance rhythms and pure improvisation, the sequences encompass outer-space-like tweaks from Michael Waisvisz’s electronics, plunger spills from Bert Koppelaar’s trombone, fierce or furtive split tones from the four saxophonists and Bennink’s ruffs, rebounds and rattles while hitting every part of his kit to ratchet up excitement But the theme, which speeds up and descends in sections, maintains a steady pace due to Alan Silva’s bass holding the beat. As the reed players’ striated vibrations mock their earlier excesses and the drummer turns the beat around, surgically inserted keyboard clicks create a finale that references the introduction.

Less brash and all-encompassing, but as remarkable a session, recorded in Norway in 1982, is Detail Day Two (NoBusiness Records CD 114 nobusinessrecords.com). The first trio iteration of that long-running group, it also demonstrates the pan-nationalist ethos of free music. That’s because this multi-layered, intricately balanced 42-minute improvisation was created by Norwegian saxophonist Frode Gjerstad, British drummer John Stevens and South African bassist Johnny Dyani. Practiced and matured in his percussion skills, the drummer never takes a solo, but allows his rattling drum tops and singing cymbal lines to intuit the rhythm so that the beat appears inevitable. Dyani, who had long established himself in Europe, boomerangs from volleying consistent plucks, which help push forward the narrative, to intricate stretches, picks and pulls to pinpoint individual string pressure or suction as he solos within his rhythmic functions. Adapting to this barrage from the bottom, Gjerstad starts off with tongue wiggles and intensity vibrations radiating from his soprano saxophone, and as the exposition becomes more pressurized switches to the deeper-toned tenor saxophone. Moving up from breathy snorts, his growling ghost notes and palindrome vibrations sound at various speeds and pitches to parallel Dyani’s strums and later bowed buzzes. Slowly, during the sequence’s second section, the saxophonist digs deeper into the theme and exposes all of its possible variables as he’s doubled by ricochets from the string set, with Stevens’ press rolls and bounces providing controlling and comforting accompaniment. Variations explored from all sides of the sound triangle, spidery fingering, positioned reed smears and drum clatter cease at the appropriate moment, never climaxing, but suggesting further trio explorations lie ahead.

Less brash and all-encompassing, but as remarkable a session, recorded in Norway in 1982, is Detail Day Two (NoBusiness Records CD 114 nobusinessrecords.com). The first trio iteration of that long-running group, it also demonstrates the pan-nationalist ethos of free music. That’s because this multi-layered, intricately balanced 42-minute improvisation was created by Norwegian saxophonist Frode Gjerstad, British drummer John Stevens and South African bassist Johnny Dyani. Practiced and matured in his percussion skills, the drummer never takes a solo, but allows his rattling drum tops and singing cymbal lines to intuit the rhythm so that the beat appears inevitable. Dyani, who had long established himself in Europe, boomerangs from volleying consistent plucks, which help push forward the narrative, to intricate stretches, picks and pulls to pinpoint individual string pressure or suction as he solos within his rhythmic functions. Adapting to this barrage from the bottom, Gjerstad starts off with tongue wiggles and intensity vibrations radiating from his soprano saxophone, and as the exposition becomes more pressurized switches to the deeper-toned tenor saxophone. Moving up from breathy snorts, his growling ghost notes and palindrome vibrations sound at various speeds and pitches to parallel Dyani’s strums and later bowed buzzes. Slowly, during the sequence’s second section, the saxophonist digs deeper into the theme and exposes all of its possible variables as he’s doubled by ricochets from the string set, with Stevens’ press rolls and bounces providing controlling and comforting accompaniment. Variations explored from all sides of the sound triangle, spidery fingering, positioned reed smears and drum clatter cease at the appropriate moment, never climaxing, but suggesting further trio explorations lie ahead.

One of the progenitors of free-form improvising that was little noticed at the time but proved highly influential for exploratory music’s future, was the European tour of American clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre3, his trio with Canadian pianist Paul Bley and American bassist Steve Swallow. A previously unreleased 75-minute Austrian radio broadcast, Graz Live 1961 (ezz-thetics 1001, hathut.com) shows what baffled, energized and/or influenced contemporary musicians. Running through 11, mostly Giuffre-composed tracks, encompassing multiple moods, speeds and pitches, the trio uses the concert setting to extend performances. A later classic like Cry Want, for instance, benefits as the heartfelt compassion in the title is made more palpable in the clarinetist’s a cappella introduction, framed by Bley’s dispassionate comping and Swallow’s swaying pumps, so that Giuffre’s ultimate shrills become that much more rending. It’s the same with the sequences that make up Suite for Germany. With a piano countermelody challenging the reedist’s initial high pitches, it’s Swallow’s unselfconscious walking which keeps the pieces together. Keyboard colouring helps slide the next section into an expression of carefully weighed tones from Giuffre with circular breathed continuum. Yet the subsequent fills Bley feeds into the narrative confirm an elaboration of mid-range swing. Reed peeps and piano slashes harden the following line but without compromising the rhythmic impetus, concluding with widening clarinet lows and double bass strums. Subverting the accusation of effete chamber-jazz, the set includes a collection of clattering from the plucked and stopped strings of a prepared piano; climbing shrills and soaring peeps from the clarinet; and guitar-like facility in expression and rhythm from the bassist. Pauses and hesitancy allow the trio to savour and stretch more beautiful motifs, yet at the same time, as on Trance, Bley backs Swallow’s string finesse with piano-lid slams that create extra percussiveness.

One of the progenitors of free-form improvising that was little noticed at the time but proved highly influential for exploratory music’s future, was the European tour of American clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre3, his trio with Canadian pianist Paul Bley and American bassist Steve Swallow. A previously unreleased 75-minute Austrian radio broadcast, Graz Live 1961 (ezz-thetics 1001, hathut.com) shows what baffled, energized and/or influenced contemporary musicians. Running through 11, mostly Giuffre-composed tracks, encompassing multiple moods, speeds and pitches, the trio uses the concert setting to extend performances. A later classic like Cry Want, for instance, benefits as the heartfelt compassion in the title is made more palpable in the clarinetist’s a cappella introduction, framed by Bley’s dispassionate comping and Swallow’s swaying pumps, so that Giuffre’s ultimate shrills become that much more rending. It’s the same with the sequences that make up Suite for Germany. With a piano countermelody challenging the reedist’s initial high pitches, it’s Swallow’s unselfconscious walking which keeps the pieces together. Keyboard colouring helps slide the next section into an expression of carefully weighed tones from Giuffre with circular breathed continuum. Yet the subsequent fills Bley feeds into the narrative confirm an elaboration of mid-range swing. Reed peeps and piano slashes harden the following line but without compromising the rhythmic impetus, concluding with widening clarinet lows and double bass strums. Subverting the accusation of effete chamber-jazz, the set includes a collection of clattering from the plucked and stopped strings of a prepared piano; climbing shrills and soaring peeps from the clarinet; and guitar-like facility in expression and rhythm from the bassist. Pauses and hesitancy allow the trio to savour and stretch more beautiful motifs, yet at the same time, as on Trance, Bley backs Swallow’s string finesse with piano-lid slams that create extra percussiveness.

Another pianist, who like Bley has been thoroughly involved with a variety of styles and ensembles, is UK-native Keith Tippett, although there’s no record of him utilizing the back-fall for its rhythmic qualities. However on the title track of The Unlonely Raindancer (Discus 81 CD discus-music.co.uk), the sheer audacity of his improvisation reaches such a height that his vibrations on the keyboard and inner strings become so inadequate that he repeatedly smacks the instrument’s wood and lets loose with a couple of rebel yells. A reissue of his first solo set from 1979, the 78 minutes of what was a two-LP set, give him ample scope for full expression. Dynamically ranging through all layers of the piano with tropes that refer to bop, modal, swing and free playing, his interpretations range from sympathetic voicing, which presages intertwined stops and transitions (The Pool), to spun-out storytelling, expressed in widening spurts of emphasized textures and concentrated tonal colour-melding climaxing with echoing forward motion (Tortworth Oak). The key(s) to his creativity though are subsequent tracks that in execution and exploration are mirror images of one another – one centred around treble pitches, the second the ground bass. The latter, The Muted Melody, swiftly sweeps from kinetic to moderato as bouncing notes follow one after another in random rushes, often dipping into the deeper part of the soundboard. Further vibrating harmonics bolster and expose the playing which gallops to the end in speed mode. Concentrating on the harshest pitches that can be reverberated from highest keys in the first section of the more-than-19-minute Steel Yourself / the Bell, the Gong, the Voice, Tippett later creates Big Ben-like bongs from the wound string set. Ultimately reaching the midway mark, he switches strategies from chord plucking to sweeping to a groove that highlights strength as well as swing. As his power voicing reaches a point where the sequence can’t become any thicker or cramped, he sophisticatedly diminishes the pressure with responsive strumming that echoes even after the final pluck.

Another pianist, who like Bley has been thoroughly involved with a variety of styles and ensembles, is UK-native Keith Tippett, although there’s no record of him utilizing the back-fall for its rhythmic qualities. However on the title track of The Unlonely Raindancer (Discus 81 CD discus-music.co.uk), the sheer audacity of his improvisation reaches such a height that his vibrations on the keyboard and inner strings become so inadequate that he repeatedly smacks the instrument’s wood and lets loose with a couple of rebel yells. A reissue of his first solo set from 1979, the 78 minutes of what was a two-LP set, give him ample scope for full expression. Dynamically ranging through all layers of the piano with tropes that refer to bop, modal, swing and free playing, his interpretations range from sympathetic voicing, which presages intertwined stops and transitions (The Pool), to spun-out storytelling, expressed in widening spurts of emphasized textures and concentrated tonal colour-melding climaxing with echoing forward motion (Tortworth Oak). The key(s) to his creativity though are subsequent tracks that in execution and exploration are mirror images of one another – one centred around treble pitches, the second the ground bass. The latter, The Muted Melody, swiftly sweeps from kinetic to moderato as bouncing notes follow one after another in random rushes, often dipping into the deeper part of the soundboard. Further vibrating harmonics bolster and expose the playing which gallops to the end in speed mode. Concentrating on the harshest pitches that can be reverberated from highest keys in the first section of the more-than-19-minute Steel Yourself / the Bell, the Gong, the Voice, Tippett later creates Big Ben-like bongs from the wound string set. Ultimately reaching the midway mark, he switches strategies from chord plucking to sweeping to a groove that highlights strength as well as swing. As his power voicing reaches a point where the sequence can’t become any thicker or cramped, he sophisticatedly diminishes the pressure with responsive strumming that echoes even after the final pluck.

While this search for the new was proceeding in Europe, North American free jazz musicians faced a commercial atmosphere that promoted soul-jazz and jazz-rock above all else. As fascinating sociologically as musically, 1973’s Sounds of Liberation (Corbett vs. Dempsey CvsD CD 057 corbettvsdempsey.com) details how one Philadelphia-based sextet attempted to affect a musical détente between progressive and pop. A song collection driven by fluid foot-tapping rhythms from drums, congas and percussion, the tracks often contrast power slaps from Khan Jamal’s vibes with glossy picking from guitarist Monnnette Sudler. Seconding both, Byard Lancaster’s silky flute puffs fasten onto poppy Herbie Mann-like tropes, while his alto saxophone split tones on tracks like Sweet Evil Mist are raunchy enough to fit any James Brown disc of the era. If this faceoff between funky and freedom wasn’t enough, Backstreets of Heaven, the longest track, goes a step further than the then-popular so-called spiritual jazz and the likes of saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and vocalist Leon Thomas, by adding unnamed male and female vocalists on top of the chugging guitar riffs, clanking vibes and overblowing reed snarls. With a call-and-response Motown-smooth delivery, the track seems aimed at the R&B singles market – that is if it wasn’t nearly 11 minutes long.

While this search for the new was proceeding in Europe, North American free jazz musicians faced a commercial atmosphere that promoted soul-jazz and jazz-rock above all else. As fascinating sociologically as musically, 1973’s Sounds of Liberation (Corbett vs. Dempsey CvsD CD 057 corbettvsdempsey.com) details how one Philadelphia-based sextet attempted to affect a musical détente between progressive and pop. A song collection driven by fluid foot-tapping rhythms from drums, congas and percussion, the tracks often contrast power slaps from Khan Jamal’s vibes with glossy picking from guitarist Monnnette Sudler. Seconding both, Byard Lancaster’s silky flute puffs fasten onto poppy Herbie Mann-like tropes, while his alto saxophone split tones on tracks like Sweet Evil Mist are raunchy enough to fit any James Brown disc of the era. If this faceoff between funky and freedom wasn’t enough, Backstreets of Heaven, the longest track, goes a step further than the then-popular so-called spiritual jazz and the likes of saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and vocalist Leon Thomas, by adding unnamed male and female vocalists on top of the chugging guitar riffs, clanking vibes and overblowing reed snarls. With a call-and-response Motown-smooth delivery, the track seems aimed at the R&B singles market – that is if it wasn’t nearly 11 minutes long.

Listening anew to these discs provides a rethinking and better understanding of the musical currents of those times.

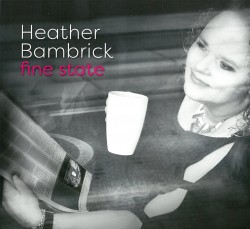

Fine State

Fine State