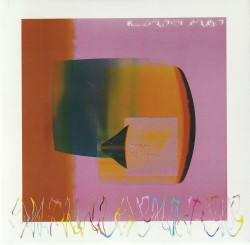

Eldritch Priest – Omphaloskepsis - Eldritch Priest

Eldritch Priest – Omphaloskepsis

Eldritch Priest – Omphaloskepsis

Eldritch Priest

Halocline Trance (haloclinetrance.bandcamp.com)

If you’re going for your debut release, a small bit of self-contemplation is cool. Although be careful, you might see yourself and like it. These are the sediments my eyes smelled when listening to Omphaloskepsis by Eldritch Priest: Puzzling that an ever-changing guitar melody doesn’t mind existing above happily lumbering distorted harrumphs; Sometimes there aren’t screeches; A double bass, sturdy as an oak, creeps along the ground as though swallowing a whale; The frothy harmonies are so eager!; You could start a band with the amount of effects pedals used; That band name should be Cluster Gardens; I averted my emotions just in time for the fizzy notes that are like eating an orange while making love; Every time there is an interruption in the melodic material, a sonata dies.

I’m not sure if Priest will perform this music live, but if he does, I do hope the audience is supplied with enough pogo sticks. Bravo For Now.