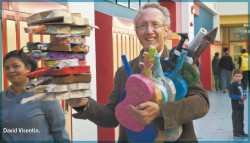

Even when you arrive slightly late to the party, you sometimes still get to have your cake and eat it too. In terms of having his cake, David Visentin was only eight years old when he started playing the violin. Various relatives were playing fiddle at the time; one was also a jazz violinist; and his own brother, who started on the piano, later switched to violin as well. He was well on his way.

Even when you arrive slightly late to the party, you sometimes still get to have your cake and eat it too. In terms of having his cake, David Visentin was only eight years old when he started playing the violin. Various relatives were playing fiddle at the time; one was also a jazz violinist; and his own brother, who started on the piano, later switched to violin as well. He was well on his way.

Still, even when you have made all the right choices, the personal trajectory of a career musician can begin to pall, as it did for Visentin, 16 years into a comfortable and satisfying association with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. After performing onstage at the plush, 2,300-seat Centennial Concert Hall for the umpteenth time, Visentin says, “We would go out into minus 30–40 degree weather — this was average for us — but the tragedy of that weather is that there are people who live outside. There is still a very large urban Aboriginal population and, many times on these evenings, we would pass people sniffing glue — because that was the big epidemic happening at the time in downtown Winnipeg.

“I remember this occasion, I’d already been thinking about the relevance of what I was doing on stage as a musician for audiences that would get out to warm parking lots and get into warm cars to warm homes. I was trying to reconcile what I call the distance between the stage and the sidewalk. The next morning, I read the headline in the newspaper that one of them had died and another was still in a coma — and it really came home to me personally that what I was doing on that stage had very little relevance to the sidewalk. I felt that if my art was to have any meaning, it had to extend further.”

“I remember this occasion, I’d already been thinking about the relevance of what I was doing on stage as a musician for audiences that would get out to warm parking lots and get into warm cars to warm homes. I was trying to reconcile what I call the distance between the stage and the sidewalk. The next morning, I read the headline in the newspaper that one of them had died and another was still in a coma — and it really came home to me personally that what I was doing on that stage had very little relevance to the sidewalk. I felt that if my art was to have any meaning, it had to extend further.”

In retrospect, he admits, “I wish I had come to that conclusion earlier.” He was in his early 40s, and it would still be a few years before he was to be offered the position of associate dean of the Glenn Gould School, and dean of the Young Artists Performance Academy at the Royal Conservatory. “And guess what? I was being offered the opportunity of training the next generation of musicians like myself.”

Then came a series of events in 2009 that was to change his life forever. It’s what Visentin describes as “an amazing Celebration of Music Week, where Venezuela essentially came to Toronto and took it over.” The prestigious Glenn Gould prize, which “promotes the vital connection between artistic excellence and the transformation of lives,” was being awarded to Dr. Jose Antonio Abreu, the founder of El Sistema in Venezuela.

To celebrate the occasion, Gustavo Dudamel, often regarded as the poster child for El Sistema and now the director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, led the Simón Bolívar Orchestra of Venezuela in their Canadian debut. Among the many events being held were 14 intimate concerts at high schools and community youth centres featuring Venezuelan chamber ensembles, an international music symposium and a climactic concert for 14,000 students at the Rogers Centre.

As a member of the board of the Glenn Gould Foundation, Visentin was in the front row of these events and was so blown away by the calibre of the young Venezuelan musicians that he spoke to Abreu and offered his services to El Sistema. He was invited as a masterclass guest artist for two weeks, to teach at various centres throughout Venezuela.

Now the executive and artistic director of Sistema Toronto, Visentin has found in this remarkable program a way of bridging the stage and the sidewalk that he has long sought. Begun as a social rescue program in 1975 among the most poverty-stricken and violent neighbourhoods in Venezuela, El Sistema has transformed the lives of more than a million children in Venezuela alone — and the program is rapidly gaining traction in many parts of the world.

It’s been said that El Sistema has brought the joy of achievement, the motivation to strive for personal growth and betterment and the love of learning to children who would otherwise be part of a lost generation. Visentin points to an important distinction: “Sistema describes itself as a social program through music, not a music program that has social benefit.” Abreu describes it thus: “The orchestra and chorus are more than artistic structures, they are models and schools of social life because to play and sing together means to intimately coexist while striving toward perfection and excellence, to follow a rigorous regimen of discipline and coordination and to seek harmonic integration, to foster ethical and aesthetic values in the awakening of sensibility and forging values.”

Abreu refers to Mother Teresa as having been the one who realized that the most tragic aspect of poverty is not the lack of bread or a roof overhead, but the feeling of insignificance that poverty breeds, the lack of identity and self-worth that all too often spirals into violence. In contrast, it is the redemptive role of music that leads to the child’s becoming a role model for the family and community, by inspiring in the child a sense of responsibility, perseverance and punctuality and eventually inspiring new hopes and dreams.

Abreu refers to the world crisis invoked by the historian Arnold Toynbee — not the economic crisis which everyone seems to talk about, but a spiritual crisis for which religion offers no solution. It is now only art in the form of music, Abreu says, that can synthesize the wisdom of the ages and provide creative space for culture in the community, not just as a luxury for the elites, but as something in which all can truly participate.

Visentin agrees: “I believe that poverty has many faces. While Toronto is not Caracas and Canada is not Venezuela, we don’t have the extremes of poverty and violence that are expressed in Venezuela, but we do have poverty and we do have violence and that’s where there’s no difference between Canada and Venezuela.

“Dr Abreu is passionately opposed to the waste of time — ‘the perverse use of leisure time’ is what he calls it. Time-wasting, for Abreu, could mean being forced to sell T-shirts eight hours a day in Caracas to make money for your family or it could be wasting time in front of the computer when you could be putting it to productive use or it could be gang membership.

“Poverty needs to be seen in more than just a socioeconomic context. Poverty of spirit is no respecter of class, because that’s ultimately where everyone meets, even in contexts where people seem to have everything going for them. It’s a great leveller when you see that everyone has parts of themselves that are impoverished. Some have the means to address them, some do not. And this is where Sistema has a value.”

Visentin describes this as a shift in awareness: “When you are looking at it through a different lens, it changes everything that you deliver — your knowledge and your experience. Because I can teach a violin lesson, I can coach an ensemble, I can conduct an orchestra, but when you’re imparting qualities of humanity — citizenship — the first thing you have to do is turn the mirror on yourself and look at what it is you really have to give. So that again levels the playing field, because we’re all trying to be better people, better family members, community members.

He pauses for a moment before resuming: “So this question of social value is really the fundamental question that Sistema is not answering necessarily, but asking. Creating an environment, bringing people together in this joint endeavour around this body of great literature and art, with remarkable results. We see everything as inextricably linked. It’s quite wondrous and frightening at the same time because there’s no way to be separate, you have to belong in a way that draws the best out of you or it draws you away, I don’t think there’s a neutral ground.”

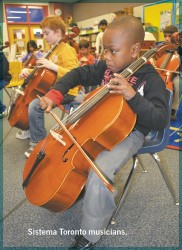

Now into its second year, Sistema Toronto offers its after-school program to 80 young string players from Grades 1–6, who come in for two and a half hours a day, four days a week, 38 weeks a year. Explains Visentin, “We ask only three things: to see themselves as a team, to always help each other and to always do your best.” It’s the same dictum that applies to their teachers, all accomplished musicians, who are selected as much for their passion for their craft as for their ability to teach.

On any of these days, as three o’clock approaches, music stands are wheeled out, chairs whisked into place and various string instruments assiduously tuned in anticipation of the children who will play them. “We’re often asked: what’s the curriculum, what’s the pedagogy, where are the texbooks, where’s the handbook?” says Visentin. “There’s no one-size-fits-all approach. The beauty is that it’s created in each community.” At Parkdale Junior and Senior Public School, for example, in addition to classical works, they also learn Tibetan folk songs and stories that reflect the Hungarian Roma community, not to mention The Great Canadian Story, a composition by one of their teachers, Ronald Royer. Visentin sees this as an opportunity for the children to express themselves not just to their own community but to the other communities where they are inevitably invited to perform, forming a network of communal music making.

For its own part, Sistema Toronto is already looking to extend its program beyond Parkdale Junior and Senior Public School. Last year, Peter Oundjian, director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, was appointed the first honourary music ambassador for Sistema Toronto’s Playing to Potential music education program, with its focus on rehearsing and performing as a member of an orchestra. At the same time, when Leonard Cohen was awarded the Glenn Gould Prize for lifetime achievement, he chose Sistema Toronto to receive the $15,000 City of Toronto Protégé Prize. Just the other day, a few University of Toronto students adopted Sistema Toronto for its Philanthropy and Youth project, which was up for a $5,000 prize for the best presentation.

El Sistema-inspired programs are proliferating across Canada — there are at least 12 programs being run from New Brunswick to British Columbia. “What’s very exciting, “ says Visentin, “is that there’s a momentum happening, more activity happening in Canada per capita than, I believe, anywhere else in the world, and Ontario is leading in the number of programs that are Sistema-inspired.”

Rebecca Chua is a Toronto-based journalist who writes on culture and the arts.