Once again, it’s time for The WholeNote’s annual guide to films of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in which music plays an important role. This year, circumstances prevented me from viewing more than a few movies in advance so the current guide is based on track record, subject matter and gleanings from across the Internet. Out of the 245 features from 83 countries and regions that make up the festival’s 44th edition, I’ve focused on 25, beginning with a handful of documentaries directly linked to music.

Once again, it’s time for The WholeNote’s annual guide to films of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in which music plays an important role. This year, circumstances prevented me from viewing more than a few movies in advance so the current guide is based on track record, subject matter and gleanings from across the Internet. Out of the 245 features from 83 countries and regions that make up the festival’s 44th edition, I’ve focused on 25, beginning with a handful of documentaries directly linked to music.

Directly Musical Documentaries

TIFF opens with the world premiere of Daniel Roher’s Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, inspired by Robertson’s revealing autobiography, Testimony (2016). The book is a well-written page-turner, filled with surprises and musical insights, painting a vivid picture of Toronto’s music scene in the 1950s and 1960s before Robertson et al made their name backing up Bob Dylan and transformed into The Band. The movie promises even more, blending rare archival footage and photography with iconic songs and appearances by Martin Scorsese, Bruce Springsteen, Dylan, Robertson, Eric Clapton, Peter Gabriel, David Geffen, Rick Danko, Van Morrison, Ronnie Hawkins, Taj Mahal, Jann Wenner and Dominique Robertson – a host of built-in star power, much of which will likely be present at the premiere. (And if you do take this one in, consider also checking out the TIFF screening of The Last Waltz (the nominal conclusion of the book), which will feature a live appearance by Scorsese and Robertson.)

Another Springsteen appearance: he shares the director credit with longtime collaborator Thom Zimney in Western Stars, a filmic record of his latest album. “It’s largely performance, but there is a framing to it,” TIFF co-head Cameron Bailey said [quoted by indiewire.com]. “It’s very filmic, which is what attracted me. The album and the film are both about this fading Western movie B-level star who’s looking back on his life and the decisions he’s made. That narrative and that character shape all the songs. In between the songs, you’ve got Bruce really talking about this character he invented, the story he wrote for the character, and how it reflects back on his own life as he ages and other kinds of narratives he’s had in his previous albums.”

Alla Kovgan’s Cunningham is said to be an eye-popping, entertaining 3D documentary about Merce Cunningham, the legendary American choreographer who died in 2009 at age 90. The film features 14 dances that were originally created by Cunningham between 1942 and 1972 – including 1942’s Totem Ancestor (his first collaboration with composer/life partner John Cage), 1958’s Summerspace (where Robert Rauschenberg’s pointillist costumes and decor – see our cover photo – create a camouflage effect to Morton Feldman’s music) and 1968’s Rainforest (in which Andy Warhol’s silver pillows wander around the stage; music by David Tudor). The film also mixes in archival material – some never before seen – touching on Cunningham’s early years, rehearsals, tours and “chance dance” technique, with his wry wit emerging in anecdotes.

With his latest film, David Foster: Off the Record, Canadian director Barry Avrich mixes rare archival footage, interviews and unprecedented access to the Victoria, BC-born musician, producer, songwriter and composer who has helped sell more than a half-billion records and won 16 Grammy Awards and whose collaborators include Chicago, Barbra Streisand and Andrea Bocelli. Among others, he’s discovered and/or worked with Celine Dion, Michael Bublé and Josh Groban, many of whom (and more) are featured in the doc.

As part of TIFF’s Special Events programming, triple-platinum artists The Lumineers bring their talents to Toronto with III, a visual companion to their upcoming third record of the same name. Split into three chapters, the visual album follows three generations of a working-class family in the American Northeast. Following the screening, fans will have the opportunity to experience some of The Lumineers’ upcoming release in a live performance, followed by a Q&A with the band and III’s director Kevin Phillip.

Music-Themed Movies (Including Two Musicals)

Cameron Bailey writes in his program note for Red Fields, “From award-winning dramatic filmmaker Keren Yedaya (Or, Jaffa) comes a complete surprise: her first musical. Adapting Hillel Mittelpunkt’s rock opera Mami, Yedaya fast-forwards this story of a gas station cashier from its original 1980s setting to the present day. Gorgeous traditional music shares the soundtrack with pulsing electronic beats, while inventive dance numbers lift this wild fantasia into La La Land territory.”

Programmer Diana Sanchez on Lina from Lima: “At once a delightful renovation of the musical comedy and a timely examination of the realities of migrant labour, the inventive debut fiction feature from Chilean director María Paz González tackles weighty themes with a light touch and a saucy sense of humour . . . Most remarkable are the moments when Lina’s humble surroundings transform into soundstages upon which she bursts into songs that fuse Peruvian folk music with music-video tropes and, in one of the film’s most dazzling sequences, a miniature version of a Busby Berkeley extravaganza.”

François Girard’s The Song of Names, from the book by Norman Lebrecht (slippedisc.com), is the director’s latest sweeping historical drama, about a man searching for his childhood best friend – a Polish violin prodigy orphaned in the Holocaust – who vanished decades before on the night of his first public performance. Clive Owen and Tim Roth star in Girard’s return to a music-themed film (after 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould and The Violin).

François Girard’s The Song of Names, from the book by Norman Lebrecht (slippedisc.com), is the director’s latest sweeping historical drama, about a man searching for his childhood best friend – a Polish violin prodigy orphaned in the Holocaust – who vanished decades before on the night of his first public performance. Clive Owen and Tim Roth star in Girard’s return to a music-themed film (after 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould and The Violin).

The Audition, Ina Weisse’s follow-up to her acclaimed film, The Architect, focuses on a violin teacher in a music high school in Germany who favours one of her students over her own son. “What fascinates me is the process of how music is created,” Weisse told cineuropa.org. “The husband of [star] Nina Hoss’ character is a violin maker, so this will be an opportunity to show how sounds evolve. Featuring the German-based Kuss String Quartett.

Renée Zellweger plays Judy Garland in English theatre director Rupert Goold’s Judy, an adaptation of Peter Quilter’s successful musical End of the Rainbow, which chronicles the final months of Garland’s life in London before her death in 1969. As she prepares for her five-week sold-out concert run, Garland battles with management, charms musicians, reminisces with friends and adoring fans and begins a whirlwind romance with Mickey Deans, her soon-to-be fifth husband. According to Vanity Fair, Garland’s daughter Liza Minnelli wrote on Facebook in June that “I have never met nor spoken to Renée Zellweger . . . I don’t know how these stories get started, but I do not approve nor sanction the upcoming film … in any way.”

Australian director Unjoo Moon makes her feature film debut with I Am Woman, the story of Helen Reddy who, in 1966, landed in New York with her three-year-old daughter, a suitcase and $230 in her pocket. Within weeks she was broke. Within five years she was one of the biggest superstars of her time, the first ever Australian Grammy Award winner and an icon of the 1970s feminist movement. She wrote the anthem, I Am Woman, a rallying cry for a generation of women to fight for change. Tilda Cobham-Hervey plays Reddy and Danielle Macdonald plays her friend, legendary New York-based Australian rock journalist and club owner Lillian Roxon.

With their significant others away on the battlefields of Afghanistan, a group of British women form a choir and discover the infectious joy of music in Military Wives, directed by Peter Cattaneo (The Full Monty) and inspired by true events.

Riz Ahmed (The Night Of) and Olivia Cooke star in Sound of Metal, the directorial debut of Darius Marder. According to Variety, the story follows a drummer (Ahmed), whose life and relationship with his bandmate girlfriend are turned upside-down when he unexpectedly begins to lose his hearing and he must go to great lengths to recapture the woman and the music he loves. A large number of the cast has been drawn from the deaf community.

In Coky Giedroyc’s How To Build a Girl, based on the semi-autobiographical novel by Caitlin Moran (who shares the screenplay credit), Beanie Feldstein plays a 16-year-old aspiring music critic who lands in London in the 1990s and succeeds despite the boys’ club culture of the day.

Seamless Soundtracks/Notably Musical

Antonio Banderas won Best Actor at Cannes this year for his role as a film director who reflects on the choices he’s made as his life comes crashing down around him in Pedro Almodóvar’s warmly received semi-autobiographical fable, Pain and Glory. Composer Alberto Iglesias, who has scored every Almodóvar film since The Flower of My Secret (1995), won the Cannes Soundtrack Award for his score which has been described as intense, emotional, highly inspired and moving, with echoes of impressionism imbued with melancholy.

Antonio Banderas won Best Actor at Cannes this year for his role as a film director who reflects on the choices he’s made as his life comes crashing down around him in Pedro Almodóvar’s warmly received semi-autobiographical fable, Pain and Glory. Composer Alberto Iglesias, who has scored every Almodóvar film since The Flower of My Secret (1995), won the Cannes Soundtrack Award for his score which has been described as intense, emotional, highly inspired and moving, with echoes of impressionism imbued with melancholy.

Peter Bradshaw wrote in The Guardian last May of Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, the film that would ultimately win Cannes’ Best Scenario Prize: “I was on the edge of my seat. Portrait of a Lady on Fire has something of Alfred Hitchcock – actually two specific Hitchcocks: Rebecca, with a young woman arriving at a mysterious house, haunted by the past, and also Hitchcock’s Vertigo, with its all-important male gaze, [which] Sciamma flips to a female gaze.” Sciamma’s film takes place in 1770, so Vivaldi for one plays a part in the score. But Para One (Jean-Baptiste de Laubier), who has worked on each of Sciamma’s films beginning with Water Lilies, contributed a poignant, indelible moment of great emotional power heard at the 78-minute mark. In a recent interview he said that they thought a lot about the rhythms and dances of 18th-century music, specifically in Brittany, the film’s setting. But they also talked about Ligeti and the modernity of the film. “So [Sciamma] went back to listen to Ligeti for three days and came back with a frantic pace; it was a great inspiration. We found the tempo.”

Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop’s haunting debut feature, Atlantics, won Cannes’ Grand Prize for the story of marginalized young lovers in Senegal desperately seeking a better life. Cinezik called Berlin-based electronic-music artist Fatima Al Qadiri’s score “captivating” and published part of a recent interview with the composer. “The most important [thing] in my music is the melody. This is my obsession. The repetition of melodic lines in my music gives the feeling of a meditation . . . the director wanted minimalism, with very little musical information, not to overwhelm the characters.”

A symbiotic relationship between two families, one rich, the other poor, is at the root of Parasite, Bong Joon-ho’s socially conscious thriller that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year. Called ingenious and unpredictable and a twist-laden black comedy, its musical component by Jung Jae-il consists mostly of a solo piano melody playing against cello, guitars and orchestral strings with an original song with lyrics by the filmmaker performed by Choi Woo-shik, an actor in the film.

Bradley Warren wrote in The Playlist about Bacurau, the film that shared the Cannes Jury Prize with Les Misérables: “For his third feature film, Brazilian filmmaker Kleiber Mendonça Filho splits directorial duties with Juliano Dornelles, the production designer on his first two features. It’s a logical progression for a body of work known for rich soundscapes and vivid images, but it’s also a game changer for his style. … Bacurau is the duo’s most political work yet ... it’s also their most playful effort to date. ... Music may not be as foundational to the plot of Bacurau as was the case with Aquarius, but its use still manages to stir the soul.” Mendonça Filho, quoted in the film’s presskit, described their approach: “The greatest challenge for the music in the movie is knowing when to shut up, which often happens with me. When you embrace the genre with all its narrative twists and turns, it’s better to have music. And when it all comes together, it’s very beautiful.”

Ladj Ly’s Cannes Jury Prize–winning debut feature, Les Misérables, ingeniously weaves the thematic threads of Victor Hugo’s masterpiece into an explosive contemporary narrative spotlighting France as a place of seismic political and social change. According to cinezik.org, the score by Canadian rock band Pink Noise (founded by Toronto-based Mark Sauner) is made up of consistent, unchangeable, undifferentiated electronic tablecloths that serve to maintain the film’s tension.

Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life, according to Justin Chang of the LA Times, tells the story of an Austrian peasant farmer who was imprisoned and executed in 1943 for refusing to fight for the Nazis. The film’s composer James Newton Howard said (in the film’s press notes) that scoring the film was a highly collaborative process, which began with Malick sending him a series of short clips from the film without any sound or music. “I wrote very loosely to picture, but we were able to establish the key thematic material and sonic identity of the score ... One of the early ideas Terry brought to me, was to incorporate sounds he had captured during production such as church bells from the villages, cow and sheep bells, the saw mill, sounds from the prison, and scythes in the fields,” said Howard. “I took many of those sounds and processed them into musical elements that are woven throughout the score. We chose to work mostly scene by scene where I would write something that he would react to, and then he would often mould the edit to what I had done.” The score focuses on the emotional journeys and crises of conscience of the characters with a solo violin throughout the film, embodying the connection between the two main characters, performed by none other than violinist James Ehnes.

Two Teasers

According to TIFF senior programmer Steve Gravestock, Louise Archambault’s And the Birds Rained Down features one of the most beautiful musical moments of the year, when Rémy Girard, as an ailing musician living in the Quebec countryside, is coaxed into performing at a nearby club and delivers a soulful and heartbreaking rendition of Time (from Raindogs), one of Tom Waits› best tunes.

And Jessica Kiang wrote about The Whistlers in Variety: “Corneliu Porumboiu goes large with the soundtrack, smashing into and out of scenes on abrupt, bombastic tracks, which often mimic the [film’s] whistling motif in the vibrato of an opera singer’s voice, or the exaggeratedly rolled ‘r’s and hissed ‘s’-es of Ute Lemper’s Mack the Knife, sung in the original German.”

White Lie: The Making of a Soundtrack

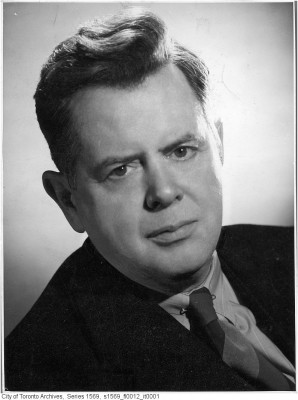

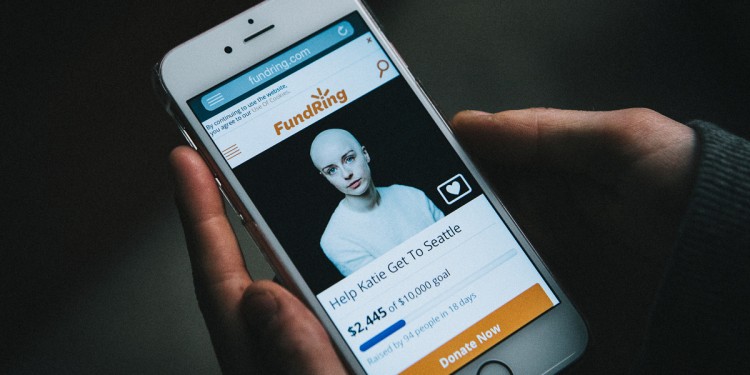

White Lie is a gripping new psychodrama, by Toronto-based co-directors Yonah Lewis and Calvin Thomas, that oozes unease as it follows a university student on her duplicitous route to crowd-funded dollars by pretending to be suffering from melanoma. It’s the duo’s fourth feature and second to be invited to TIFF (Amy George, their 2011 debut, was the first). Marked by nuanced, naturalistic acting (Kacey Rohl, Amber Anderson, Martin Donovan) and set off by striking cinematography, its mood is buttressed by a quietly disturbing score.

White Lie is a gripping new psychodrama, by Toronto-based co-directors Yonah Lewis and Calvin Thomas, that oozes unease as it follows a university student on her duplicitous route to crowd-funded dollars by pretending to be suffering from melanoma. It’s the duo’s fourth feature and second to be invited to TIFF (Amy George, their 2011 debut, was the first). Marked by nuanced, naturalistic acting (Kacey Rohl, Amber Anderson, Martin Donovan) and set off by striking cinematography, its mood is buttressed by a quietly disturbing score.

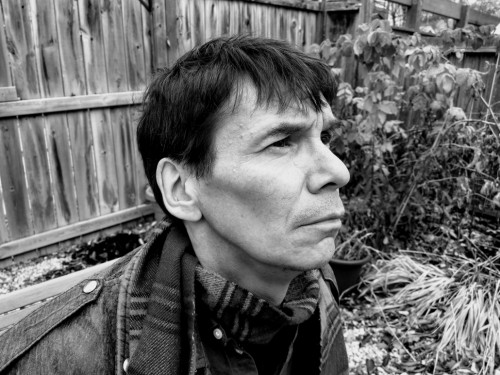

The film’s large musical component (by Yonah’s brother, Lev Lewis) is strikingly judicious: it doesn’t overwhelm and the filmmakers know when to remove it entirely. I was curious about the working relationship among Thomas and the Lewis brothers vis-a-vis the music in the film, so in a recent email I asked Yonah to describe their process.

[Full disclosure: while not members of my immediate family, Yonah and Lev are related to me.]

“We (Yonah and Calvin Thomas) always attempt the assembly and first cut without a temp track, but temptation quickly arises and pretty soon we begin to pull tracks that help us envision how we want the final scenes to feel. Lev tends to source most of the music, but the two of us occasionally bring in pieces we think might send us in the right direction. At this point in the edit, much of this is just us trying to locate the feeling and scope of the music. Sometimes we want something orchestral, maybe even bombastic, but ultimately feel that the music has to match the size of the production.

“On White Lie, we used a number of tracks from the Wojciech Kilar We Own the Night soundtrack, as well as pieces by Yusef Lateef, Steve Roach, Pere Ubu and Wadada Leo Smith, until Lev began recording his own temp score a few months into the editing process.

“We were a little rushed getting a cut ready for festival submissions and Lev had a whirlwind long weekend writing and recording a temp score in the edit suite, just him, a guitar and a MIDI keyboard. That stage of the score turned out to be a more post-punk, Sonic Youth feel than what we eventually landed on, but it helped us start to set a tone for what the music eventually became. We ended up gravitating to more strings and piano than originally discussed, but still incorporating that jagged, jarring feeling of the distorted guitars and loose percussion.”

I then contacted Lev Lewis about how he had approached writing the score, indicating that I was impressed with the depth of the recurrent cello line, the inherent pull between the jazzy foreground walking bass and the tension drip of the synths and background percussion, the way that the music gently adds to the web of deceit.

“Initially, the score was going to dominantly rely on guitars and keyboards, and since those are instruments I can play (unlike strings or woodwinds or what have you), I ended up putting more effort into the temp music than is typical,” he replied. “I recorded in the editing suite we were cutting in, using Logic and an Apogee ONE for guitars. We used this temp music for about six weeks until picture was locked and I moved onto writing the score full time. I spent about two-three weeks composing to picture and then another three weeks or so recording. Most of the recording was done out of Victory Social Club in a small office with Lucas Prokaziuk engineering. We recorded guitars and live synths there, finding the right sounds and tweaking the cues.

“We had three great string players (two violins, one cello) come in for a whirlwind day where we recorded something like 19 cues in maybe four hours, and a drummer to play the kit. I performed the piano and just banged on the percussion until we got the sounds we were looking for. Working with live synths was probably the biggest learning curve for me as it was my first time, but also quite fun, especially interesting to realize how alive they are.

“Writing a score for such a psychologically damaged character immediately gives you a lot of options, some of them interesting, some of them obvious. I had recently heard a record by Chris Corsano and Bill Orcutt which is made up of these interlocking guitar-drum runs. Really rough and abrasive but fully integrated. I incorporated (or stole) that idea and placed it overtop a more conventional horror movie melody played on piano and cello. This came together pretty quickly and became the main theme.”

And, finally, this from Calvin Thomas:

“Having the score come together really solidified the tone of the film. It made her more fascinating, more cunning, more complicated. And ultimately that’s what we were striving for: the audience should leave the theatre feeling deeply unsettled by the character they’ve been following through every scene, and conflicted by their own attachment to her.”

White Lie plays the Toronto International Film Festival September 7 and 13. Consult tiff.net for more information.

The Toronto International Film Festival runs from September 5 to 15. Please check tiff.net for further information.

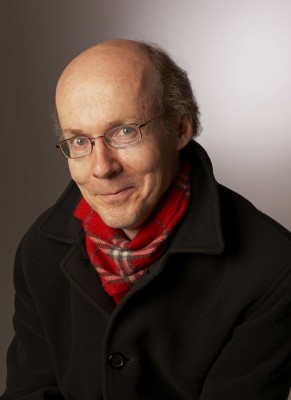

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.

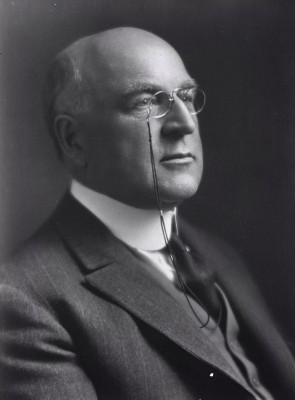

My theremin is a musical instrument, an instrument of the air. Its two antennas emerge from a closed wooden box. The pitch antenna is tall and black, noble. The closer your right hand gets, the higher the theremin’s tone. The second antenna controls volume. It is bent, looped, gold, and horizontal. The closer you bring your left hand, the softer the instrument’s song. The farther away, the louder it becomes. But always you are standing with your hands in the air, like a conductor. That is the secret of the theremin, after all: your body is a conductor …

My theremin is a musical instrument, an instrument of the air. Its two antennas emerge from a closed wooden box. The pitch antenna is tall and black, noble. The closer your right hand gets, the higher the theremin’s tone. The second antenna controls volume. It is bent, looped, gold, and horizontal. The closer you bring your left hand, the softer the instrument’s song. The farther away, the louder it becomes. But always you are standing with your hands in the air, like a conductor. That is the secret of the theremin, after all: your body is a conductor …