Springing Sweetly into Summer: It takes a fair bit to make me smile during the dog days of the March magazine production cycle. Nowhere is the pain of the fact that February is three days shorter than some months more sharply felt than right now - the last 48 hours before going to press.

But one smile got wrung out of me earlier today, while giving our annual “Orange Pages” summer music education special section (it starts on page 58) a quick last look before press time.

It’s not a section that lays claim to being comprehensive. February would need 280 days for that to happen. It’s more like a geologist’s rock sample - a rough crystal refracting the light of just how much opportunity there is out there for music lovers wanting, in the words of the little intro to this year’s section, “to engage in summer music making … when the restraints of our regular schedules have been lifted.”

I’ll confess that reading the section itself is always a bit of a bitter-sweet thing for me. No matter when in the year we publish it, it always feels as though it’s either too early or too late - either “How on earth do you expect me to plan that far ahead?” or “I wish I had known about that months ago!”

But however practical or wistful the read-through, I always come away from skimming through the 35-or-so profiles in it with a sense of vicarious pleasure. And on this occasion, with a sweetly accidental moment of amusement.

All the entries in the section are structured in a similar way, offering an anecdotal description in the provider’s own words of what the opportunity is all about, preceded by nuts-and-bolts information about the what, where and when of it all, and for whom it’s intended.

It was one of those “who it’s for” descriptors that did it! (I won’t tell you which profile it was in - you’ll have to find it yourself.) “All ages 10 to 90!” it said.

Maybe it’s just that my funny bone is tingling from too-long days of leaning on my elbows during this all-too-short production cycle, or just that, as all regular readers of this Opener will both know by now, my sense of humour is a bit aslant at the best of times! But I read “All ages 10 to 90!” and the picture jumped immediately to my mind of one particular columnist reading it and sputtering in indignation “What the hell do you mean I’m too old for that!?”

Slight as this little story may be, it speaks to a good kind of complexity, in my view of the world we live in. Namely this: that almost anything one says, especially in fun, can be taken differently than one intended. “All ages, 10 to 90” is clearly intended as a way of speaking playfully to the broad inclusiveness of the offering. It takes a darkly perverse view of things to interpret it as a deliberately ageist attempt to exclude nonagenarians from the joys of campfire life. (Hmm maybe there’s a charter challenge there somewhere. Any nine-year-olds with awesome finger-pickin’ chops want to join in?)

It’s a bit of a stretch to argue that the above anecdote serves as a reminder of how endless (and sometimes painfully rewarding) the process is of reinventing our language and re-examining our assumptions, musical and political.

Happily (if not necessarily comfortably), this sesquicentennial year offers the opportunity for the same kind of soul-searching on a much grander and more fundamental scale.

Tiptoeing the Sesquicentennial Party Line: The Toronto Consort’s “Kanatha/Canada: First Encounters” (February 3 and 4 at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre) got February off to a flying start for me. It was an early, and welcome, indication that the 2017 sesquicentennial arts bandwagon will have room, alongside the enthusiastic flag-wavers, for those who choose to look at 1867 critically, as a relatively recent milestone in a much longer, and not unequivocally celebratory, journey.

As an idea for a concert program, “Kanatha/Canada” had its roots, in the fall of 2013, in the work that constitutes the entire second half of the concert, composer John Beckwith’s Wendake/Huronia, a roughly 30-minute work, in six movements, reflecting on Wendat culture from pre-European contact to the present day and ending with a prayer for reconciliation between the two cultures.

As Beckwith himself described it in an article in The WholeNote in summer 2015, “late in 2013, John French, director of the Brookside Music Association in Midland, invited [me] to compose a piece to be performed in July 2015, marking the 400th anniversary of the voyage of Samuel de Champlain and a few fellow adventurers from France to the ‘Mer douce’ or ‘Fresh-water sea’—today’s Lake Huron. I said yes.”

In its original form the work was performed by a chamber choir drawn from local choirs, a pair of First Nations drummers, Shirley Hay and Marilyn George, an alto soloist (Laura Pudwell) and a narrator (Theodore Baerg), accompanied by the Toronto Consort. It toured Georgian Bay communities including Midland, Parry Sound (as part of the Festival of the Sound), Barrie, Meaford and others.

In the February 3 and 4 version, performed to a packed Trinity-St. Paul’s, almost the same forces were assembled. The most notable change was that the role of narrator/singer was taken by Georges Sioui, described in the concert program as a “Huron-Wendat … polyglot, poet, essayist, songwriter and world-renowned speaker on the history, philosophy, spirituality and education of Aboriginal peoples.” Sioui had played a seminal role in the gestation of the project; this performance brought his voice into the foreground.

Composer Beckwith had found Sioui as a resource early on; in fact, the fifth movement in the work, Lamentation 1642, “an angry lament” was based on a paper Sioui had given in 1992 on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage, recalling the life-patterns of Wendats in the years 992, 1492, and 1642 [the sesquicentennial of Columbus’ “discovery” of North America]. “His picture of the state of Huronia a century and a half after Columbus affected me deeply,” Beckwith writes. “When I interviewed Sioui in Ottawa, he generously gave me permission to set this ‘lament’ as my fifth panel.” Sioui also advised Beckwith not to end there. “He thought the angry lament should be followed by more optimistic sentiments, reflecting today’s efforts towards reconciliation.”

The work traverses aeons: a prologue suggesting “pre-contact” evinced by percussion imitating the sound of snowshoes while individual voices shout out, as in a roll call, the names of various Wendat clans; a second movement, set in a European-sounding contrapuntal choral style, revolving around a “poetic epigraph written by a fan” at the front of the second edition (1632) of Champlain’s published account of his travels; third and fourth panels evoking, respectively, canoeing and the Wendat “Feast of Souls”; second last, Sioui’s “angry lament”; and finally a movement titled To the Future based on an intensely moving recent poem of Sioui’s (2013), written in English but spoken here in French, in which the narrator dandles his infant nephew and asks the baby boy’s understanding for referring to child as “grandfather” because in so doing the narrator is transported to a childhood in which an optimistic future could more readily be seen.

Most interesting (in the context of this particular essay) has been watching the development of the Toronto Consort’s role (with artistic director David Fallis at the helm) in the evolution of the piece from its origins at the 2015 Brookside Festival till now. It’s not hard to see why an ensemble specializing in authentic performance of early music would have been the logical musical choice for a project examining a 400-year old moment in time. But without Fallis’ fierce curatorial intelligence, their role could have remained a kind of period window-dressing.

In this February’s concert, Beckwith’s half-hour long Wendake/Huronia has morphed from being a stand-alone work into the second half of a fully articulated concert program. The first half, anchored by First Nations drummers Shirley Hay and Marilyn George and by vocal artist Jeremy Dutcher (who was interviewed here by Sara Constant last month), is built around the 1701 “Great Peace” of Montreal in which in the words of historian Gilles Havard: “In the heat of the summer of 1701 hundreds of Native people paddled their birchbark canoes down the Ottawa River … [an] impressive flotilla made up of delegations from many nations of the Great Lakes region … and from other directions … In total about 1,300 Native delegates, representing 39 nations, would gather in the little colonial town … to participate in a general peace conference.”

As with Wendake/Huronia, the treatment of the “Great Peace” story is nuanced and layered, enriched by singer/drummers Hay and George’s deep-rooted knowledge of First Nations lore and Dutcher’s ongoing explorations “part composition, part musical ethnography and part linguistic reclamation” of his Wolostoq Maliseet (Saint John river basin) heritage. As a whole, the program immerses the audience in the ongoing complexities of contact between Canada’s Indigenous and Settler peoples. It is all the more powerful for the way it animates the Consort’s usual repertoire, which is all too often at risk of being seen as nothing more than a sentimental rendering of artfully encased museum pieces from a bygone age.

There was nothing sentimental about this particular exercise in time travel. A healthy reminder as the coming months of Sesquicentennial-themed offerings come to a boil.

Interlude: The night of July 4, 1975, I slept on the floor of the Greyhound bus station in State College, Pennsylvania. The night before I had slept on a Boeing 707 en route between what was then called Jan Smuts Airport and JFK in New York. My arrival at JFK was carefully timed: it was the first day of the US Bicentennial Year, and I was in possession of a $200, unlimited-travel, two-month bus pass, effective July 4, 1975, that I was about to make good use of. (I was seven weeks away from arriving in Toronto to stay.) There’s something to be said for ’centennial bandwagons.

The night of July 5 1975 I was back on the floor of the State College bus station again, having spent July 5 waiting fruitlessly, on the steps of the Altoona Town Hall, for a local bus that, according to Greyhound bus dispatch, would take me to Jamestown, PA. But when it arrived it was going to Johnstown, PA. So took the only other bus coming through, and slunk back to State College again.

Time travellers take note: There were worse places to be than the Altoona Town Hall steps, on July 5 1975. The Phillies and Pirates both won (against the Mets and Cubs respectively) having both lost the previous day - the Phillies in a heartbreaker. So the alarmingly large town drunk who spent much of the day keeping me company on the steps, transistor radio to his ear, was in a good mood. ….

Now, where was I? Ah yes, the State College, Pennsylvania bus station. That is where this story is headed next.

Tafelmusik at the Crossroads: Even for an ensemble accustomed to packing their bags and moving from one thing to another really quickly, Tafelmusik is in the middle of a three-month stretch requiring remarkable agility.

Tafelmusik at the Crossroads: Even for an ensemble accustomed to packing their bags and moving from one thing to another really quickly, Tafelmusik is in the middle of a three-month stretch requiring remarkable agility.

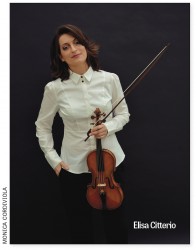

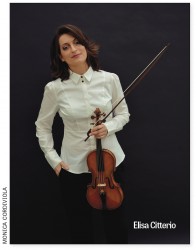

Consider the fact that, by the time you read this, within the month of February alone (28 days), the organization will have: announced the appointment of a new music director; presented 12 local performances of four different programs at five different venues; held a very effective invite-only season launch concert at an off-the-beaten-track venue (patching in their new music director Elisa Citterio by video); and launched a US tour that will take one of their most successful all-memorized thematic programs, Alison Mackay’s “Bach’s Circle of Creation” on a 12-day, eight-city US tour.

The tour will be mostly by bus. And it will take them, among other places, to (drum roll please!) State College, Pennsylvania, where at 7.30pm on March 2, the second stop of the tour, they will perform the “Circle of Creation” program in the Schwab Auditorium at Penn State University. Maybe I’ll go see that one, for old times’ sake. Although I am quite possibly getting too old to intentionally sleep in bus stations.

Elisa Citterio: Of all the headspinning details hinted in the previous description of Tafel on the move, the one with likely the most significant long-term implications is the hiring of Citterio as music director. Attesting to the care taken in finding someone to replace the irreplaceable Lamon, we as audience, and the players, have had several opportunities (November 2015, and February and September 2016) to get to know her as violinist and conductor. Her 2016/17 September season-opening Koerner Hall appearance was fascinating. In a program that included, among other things, Handel’s Water Music, Bach’s Orchestral Suite No.4 in D and excerpts from Rameau’s Les indes galantes it was clear from the get-go that there was some very intense musical conversation going on between the conductor and the orchestra. She led from the first violin, as is the orchestra’s custom, and so intent was she on maintaining the connection with the players, turned three-quarters away from the audience, that from the back of the house, there were moments of almost feeling excluded. “Wait till she realizes that that bunch of smart cookies [the players] can read her back as easily as they can read her face! She’s going to be something really special” my concert companion remarked.

I, for one, can’t wait.

We get one more chance to hear and see Citterio at work this season (early May) and then in September it’s “chocks away!” as a newly minted Tafelmusik takes flight.

Alison Mackay: Running a close second to Citterio’s appointment as significant Tafelmusik news has to be the seemingly inexhaustible flow of thematic programs from the mind of longtime Tafel bassist Alison Mackay. Her latest, “Visions and Voyages: Canada 1663-1763” will be over by the time you read this. (I’m off to see it as soon as I finish this piece!) Like the Toronto Consort’s “Kanatha/Canada” discussed earlier, it places the sesquicentennial theme in the context of a much earlier timeline. I’ll be surprised if it’s any less rigorous in its framing of the issues than its Consort counterpart.

As mentioned, an earlier Mackay program “Bach’s Circle of Creation” hits the road for a US tour February 28. And, no surprise, there’s a new one in the works for the 2017/18 season. Titled “Safe Haven,” it “explores the musical ideas of baroque Europe’s refugee artists ... portraying the influence of migration on the musical life of Europe and exploring how the movement of refugees changed and enriched the economy and culture of major cities.

Mackay’s programs increasingly demonstrate a committed and almost uncanny knack to to tap into history truthfully so that an audience comes away, by analogy, with a clearer understanding of issues of our time. (“Tales of Two Cities: The Leipzig-Damascus Coffeehouse” last spring was a perfect case in point.)

Coda: The Time-Traveller’s Toothbrush

“The only thing I really need to do before a concert is to brush my teeth. I cannot sing with dirty teeth. … But otherwise, a little warmup, some nice clothes, a bit of lipstick … I’m good to go.”

The speaker is alto powerhouse Laura Pudwell, longtime Toronto Consort member, quoted in the program for “Kanatha/Canada” discussed earlier. As for this ink-stained wretch, though, hopping around from topic to topic, all the while pretending at cohesion, the counterpart of the Pudwell pre-performance toothbrush is of course a catchy headline. Trust me.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.

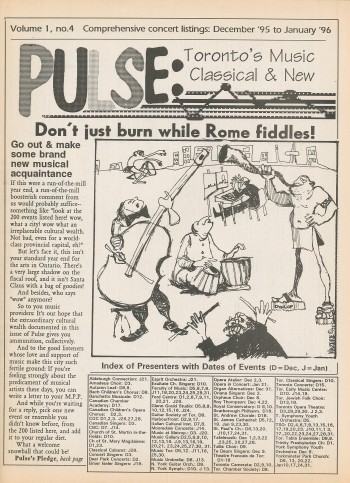

Sometimes the way I can tell that things are going well around here is by noticing how small, in the overall scheme of things, the things I am fretting about actually are. Like two days ago when I found myself agonizing about whether it would be more accurate, on the cover, to describe this two-month issue as “combined” or “double.” “Double,” I told myself, is how I think we have usually done it. But with the concert scene being significantly put on hold in the latter part of December, for Festivus or whatever you choose to call it, and the first couple of weeks of January significantly dedicated to recovery, there isn’t double the amount of activity. “Combined” would be more accurate. I went searching for answers in our “rear view mirror” – the complete 23-year flip-through archive of this publication on our website – to see what we’ve done in the past, all the way back to Vol 1 No 4 in December 1995. (Click on Previous Issues under the “About” tab.)

Sometimes the way I can tell that things are going well around here is by noticing how small, in the overall scheme of things, the things I am fretting about actually are. Like two days ago when I found myself agonizing about whether it would be more accurate, on the cover, to describe this two-month issue as “combined” or “double.” “Double,” I told myself, is how I think we have usually done it. But with the concert scene being significantly put on hold in the latter part of December, for Festivus or whatever you choose to call it, and the first couple of weeks of January significantly dedicated to recovery, there isn’t double the amount of activity. “Combined” would be more accurate. I went searching for answers in our “rear view mirror” – the complete 23-year flip-through archive of this publication on our website – to see what we’ve done in the past, all the way back to Vol 1 No 4 in December 1995. (Click on Previous Issues under the “About” tab.)