In an article that will be featured in the forthcoming summer issue of the Canadian Music Centre’s digital magazine, Notations, composer John Beckwith writes about how, late in 2013, John French, director of the Brookside Music Association in Midland, invited him to compose a piece to be performed in July 2015, marking “the 400th anniversary of the voyage of Samuel de Champlain and a few fellow adventurers from France to the ‘Mer douce’ or ‘Fresh-water sea’—today’s Lake Huron. I said yes,” says Beckwith. The Ontario Arts Council approved the commission, and, effectively, that’s where the story of Wendake/Huronia, as the work is titled, begins.

In an article that will be featured in the forthcoming summer issue of the Canadian Music Centre’s digital magazine, Notations, composer John Beckwith writes about how, late in 2013, John French, director of the Brookside Music Association in Midland, invited him to compose a piece to be performed in July 2015, marking “the 400th anniversary of the voyage of Samuel de Champlain and a few fellow adventurers from France to the ‘Mer douce’ or ‘Fresh-water sea’—today’s Lake Huron. I said yes,” says Beckwith. The Ontario Arts Council approved the commission, and, effectively, that’s where the story of Wendake/Huronia, as the work is titled, begins.

Brookside’s John French first described the undertaking to me back in April: “The new work will be performed by a chamber choir, the Brookside Festival Chorus, comprised of members of regional choirs, a pair of First Nations drummers, Shirley Hay and Marilyn George, Laura Pudwell, alto, and Theodore Baerg, narrator, accompanied by the Toronto Consort under the direction of David Fallis. It’s a 30-minute work in six movements, reflecting on the Wendat culture from pre-European contact to the present day and ending with a prayer for reconciliation between the two cultures. It will be presented in a tour of Georgian Bay communities including Midland, Parry Sound (as part of the Festival of the Sound), Barrie and Meaford and potentially others.”

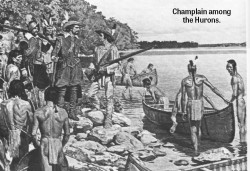

In the upcoming Notations piece, Beckwith describes his reasons, socio-political and musical, for taking on the project. “I had encountered Champlain’s history 25 years before, in preparing Les Premiers hivernements (First Winterings), a work for two voices and chamber ensemble commissioned by the Toronto Consort, that concerned Champlain’s earlier voyages in what is now Nova Scotia. … The new proposal immediately intrigued me, and has occupied much of my composing energy for over a year. My paternal forebears were New England immigrants who came about a decade after Champlain’s venture. I imagined Europeans in that era [planting] … a flag and [announcing], ‘This land now belongs to the King of Spain (or France, England, or Holland).’ Ownership of land was not part of the indigenous way of thinking. The Wendats, inhabitants of Huronia for several generations (without feeling they “owned” it) were ready to share with the French newcomers: native canoes and native paddlers had brought Champlain to the territory.”

Champlain’s arrival led to profound changes: “By mid-century, the Wendat villages were abandoned,” Beckwith writes, “and the survivors dispersed, some to a reserve near Quebec City and others to the Midwest, where the name survives as ‘Wyandot.’”

Champlain’s arrival led to profound changes: “By mid-century, the Wendat villages were abandoned,” Beckwith writes, “and the survivors dispersed, some to a reserve near Quebec City and others to the Midwest, where the name survives as ‘Wyandot.’”

“This is a truly unique work for several reasons,” says John French. “From the outset the composer and commissioner were sensitive to the First Nations attitude toward the events being planned to commemorate Champlain. The Huronia Museum is working with a firm to design and install a new gallery devoted to the First Nations. The opening of the new gallery is coincident with the tour of this composition and both will highlight the fact that the Wendat people are an extant culture. As revealed by Kathryn LaBelle in her recent book, they were dispersed but not destroyed. The museum will be providing a travelling exhibit to accompany the tour. Also, the composer has worked closely with Georges Sioui, head of Aboriginal Studies at the University of Ottawa, for advice and content for the piece. Professor Sioui, himself of Wendat heritage, has embraced this project and his poetry will provide the text for some of the movements. He will also be working with the choir on pronunciation of the Wendat language. The composition will be sung in French and Wendat.”

Reconciliation is, as French stated earlier, an overall goal of this undertaking. It is also explicitly the theme of the work’s final movement. But truth of necessity comes first in the phrase “truth and reconciliation,” so the work’s first five movements have a large chunk of truth to tell first, in a very short work that cannot resort, as historians can, to ponderous didacticism. Beckwith’s solution as composer has been to provide what he calls an “impressionistic summary of the Wendat experience, before and after Champlain.”

“For a prologue suggesting ‘pre-contact’ I chose a feature that the French visitors found novel and remarkable: snowshoes. Against percussion imitating the sound of this mode of travel, individual voices shout out, as in a roll-call, the names of various Wendat clans.”

The second movement, set in a European-sounding contrapuntal choral style, revolves around a “poetic epigraph written by a fan” at the front of the second edition (1632) of Champlain’s published account of his travels. “It employs the then-brand-new terms Canada and La Nouvelle France and elaborately extols Champlain, his ventures and his writings,” Beckwith says.

The third and fourth panels evoke, respectively, canoeing and the Wendat “Feast of Souls.” “Once a decade or so, villagers would disinter their deceased and transport their remains to an agreed central place where in a week-long ceremony of dancing and chanting they would rebury them in a common plot, with furs, food, ceramics and other artifacts. The early French observers all mention this festival.”

The fifth movement “an angry lament” is based on a paper George Sioui gave at Laval University in 1992 on the 500th anniversary of another famous voyage, that of Columbus, and recalls the life-patterns of Wendats in the years 992, 1492, and 1642. “His picture of the state of Huronia a century and a half after Columbus affected me deeply,” Beckwith writes. “He imagines a young Wendat, having lived through the crisis of European ‘takeover,’ calling on the Great Spirit to restore his people to their former dignity. When I interviewed Sioui in Ottawa, he generously gave me permission to set this ‘lament’ as my fifth panel.”

But Sioui also advised Beckwith not to end there. “He thought the angry lament should be followed by more optimistic sentiments, reflecting today’s efforts towards reconciliation.”

The involvement of indefatigable David Fallis as conductor and the Toronto Consort as musicians completes the picture for this fascinating project. “Among the Consort’s available instruments, I chose those most suited to a 17th-century Canadian setting: recorders, lute, mandolin, viola da gamba, chamber organ and (a first in my composing experience) hurdy-gurdy,” Beckwith states. On the percussion side he opts mainly for drums, rattles, sticks and scrapers. “I felt I should avoid metal percussion,” he says. “But on learning that small bells were favoured at that time as trade items I allowed myself a hand-bell. Shirley Hay, one of the First Nations drummers, sang me, to her own drum-beat, a traditional Ojibwe ‘mourning song,’ and gave me permission to quote it as a coda to the Feast of Souls movement. She will sing it in the premiere, with phrases repeated by the choir, as if she is teaching it to them.”

All in all it sounds like a carefully thought through, lovingly crafted, deeply felt endeavour that will bring a truthful resonance to this summer’s planned 400-year celebrations of Huronia that might otherwise serve only to add discordant insult to historical injury.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.