The following story is based on a videotaped conversation at The WholeNote between Angela Hewitt and David Perlman on November 12, 2014 . Click the image below to view/hear the entire conversation.

As Pamela Margles notes in her review of of Angela Hewitt’s newly released Bach: Art of the Fugue in this issue of The WholeNote (page 77 of the print edition) “it was four years ago that Hyperion released all of Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt’s recordings of Bach’s solo keyboard works as a 15-disc boxed set. It was a huge project, but it didn’t include Bach’s monumental late work, The Art of the Fugue.”

“That is when everyone started writing to me of course,” says Hewitt. “You know, why haven’t you done The Art of the Fugue.” She hadn’t even performed it before then, she says, let alone contemplated recording it. “Growing up, it wasn’t even really considered a keyboard piece, or even anything you performed much. For one thing it had long been considered something of an academic work – Bach seeing what he could do with fugues, double fugues, triple fugues, mirror fugues. And there was the fact that in the first edition it was written as an open score, one voice per stave, like a string quartet.”

But then, after the boxed set appeared and the letters started, the Royal Festival Hall asked Hewitt to perform two concerts for the 2012/13 season, “one in the autumn and one in the spring, with programs that somehow matched up. So I thought here’s my chance to do the Art of Fugue because then I can present it in two halves and work on it better than playing it all at once the first time. I matched it with late Beethoven which was the perfect thing to team it up with. And so for that whole year and a half, even though I played it in two halves, I played it a lot.”

She played it in its entirety for the first time at her own festival, in Trasimeno, Italy, in the summer of 2013 and then recorded it the following month. “With something like that,” she says, “I would never go into the recording studio without performing first. It’s just too important to have performances as part of the experience.”

As a single performance it’s a massive work, I observe. “It is. It’s 90 minutes, and I play it without an intermission. But in London, two nights ago, the audience was so quiet and it was in a beautiful church with beautiful sound and a Fazioli piano and it was just bliss. I think it’s a special experience when you can hear a piece that’s that long and create a mood and sustain it; and with something like that it’s worth it.”

I remind her of the last time someone from The WholeNote interviewed her (Pamela Margles who wrote the aforementioned Art of the Fugue review) It was in 2007 in Trasimeno, just before her festival, the summer before she launched out on a sustained world tour in support of her recording of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (including back-to-back performances in October 2007 at the Glenn Gould Studio in Toronto).

“I think that was something like 110 dates in 26 countries on 6 continents over 14 months” she says. “I’m not the kind of artist who travels with the same recital program all year round. I don’t do that at all. But with the Well-Tempered it’s such a challenge to get up night after night and play it (on most occasions from memory). I always went out on stage thinking okay I’m going to try to get it better tonight, By the end of the 14 months I think I’d had enough but I covered so much of the world and brought that music to so many people. ”

So will there be anything on that scale in support of The Art of the Fugue? I ask.

“Not in the same way. I have been performing it a lot. I performed it two nights ago in London; I’ve played it in Glyndbourne in the opera house, at my festival and other places in Italy, I’ll be playing it in April in Sao Paulo, Wigmore Hall, ... so its something that will remain in my repertoire for many years to come.”

In terms of her assertion that she is not the kind of artist who travels with the same program year round, deeds speak! Her hastily arranged November 12 2014 visit to The WholeNote for this interview came less than two days after Art of the Fugue in Hampstead; the next day she was off to the Aurora Cultural Centre, north of Toronto, for a recital. It’s interesting to me that she still has time and appetite for small venues like Aurora. “I’ve always done that,” she says. “I suppose at the stage I am now I could do away with such things, but it would be a loss for me and for the people in those communities. You know, you can often play a program there that you have to play in Carnegie Hall so it’s very useful in that regard but that’s not the reason.”

So what will her Aurora program be, I ask. “It a big one” she says, “That’s two big programs this week. I’m playing the fifth partita of Bach, which I haven’t played in many years, but was one I played in my teenage years so I remember it pretty well ... Beethoven, his second last sonata, in A flat major, Op.110 (which of course has a fugue in it in the last movement and which I recorded and will be released next year); then after intermission a group of four Scarlatti sonatas, which I’ll be recording in February; Albeniz, three extracts from the Suite Espagnole, because the links between Scarlatti and Spanish music are very close, ... and then, to finish off, the big “Dante” Sonata by Liszt, which I’ve also recorded and will be out soon after the new year.”

The number of recordings, all with Hyperion, recent and upcoming, is dizzying.”

The relationship with Hyperion started back in 1994, she tells me, and it’s a story with a bit of a twist. “l actually sold them my first recording which was the Bach Inventions. I had done the Deutsche Grammophon record after I won the prize here in 1985, the Bach Competition; that record had done very well but the marketing people, even back then they said unless I made some scandal they didn’t know how to market me – it wasn’t enough just to play the piano well. I waited many, many years before making another record and then wasn’t willing to wait any more. I got my former producer from Deutsche Grammophon (he had retired by then) and he got this young sound engineer Ludger Böckenhoff who was freelancing for Deutsche Grammophon, very brilliant, a wonderful guide, we’ve been together 20 years ...

“Anyway, Hyperion took on that first Bach recording but only if I would record the complete Bach. I said sure! So that was back in 1994 I started with Hyperion, run then by the formidale Ted Perry, now by his son Simon.”

Clearly it’s a good match: “three or four CDs a year which very few pianists do in today’s climate; wonderful repertoire: Beethoven sonatas, Mozart concertos, but also a lot of French music – Chabrier, Couperin, Rameau, Messiaen, the complete Ravel, Debussy, ... incredible discography, and lots of projects into the future.” She could be with a bigger name label now, she says, “but what does bigger label mean these days? I mean I could be with a label that gives you more actual PR, if that’s what you want but I have all the musical integrity of being with Hyperion and doing what I want.” Add an astoundingly vigorous concert schedule to the equation and one can see why it is that Hewitt’s performing and recording plans are mapped out further into the future than most.

“Do you take your piano with you?” I ask, half joking. She smiles. “Sometimes,” she says. “I have two concert grands, one here in Canada which is sometimes in Toronto, sometimes in Ottawa. Right now it’s in Toronto. It’s a Fazioli concert grand. (I’ll be performing on it at Koerner Hall January 9 with Anne Sofie von Otter); and then I have one in Italy, at my home there that I use for my festival and for concerts in Italy. But I also took it to Finland, can you imagine, by truck and by boat in January, across the Bay of Finland from Germany, and arrived safely.”

The occasion, she explains, was for her recording of Messiaen’s Turangalila with the Finnish Radio Philharmonic Orchestra. “When I make a recording that’s special I need to have the best piano otherwise why bother making the recording, it doesn’t make sense. So I need to have my own pianos for that. My Fazioli pianos are wonderful, such colour and response and I am really happy playing them. So sometimes I take it but it’s usually a question of money. If it didn’t cost anything I would take it everywhere.”

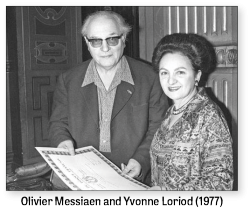

Perhaps not as precious as her beloved nine-foot Fazioli with the four pedals, but precious enough, tucked into her score of Turangalila is a letter from Messiaen’s widow, Yvonne Loriod, who sent Hewitt the letter and score in London some 14 years after their first meeting at the 1985 Toronto International Bach Competition that set Hewitt on the road as a concert pianist. Messiaen and Loriod were both on the jury, and in the semi-final round the young Hewitt pulled out a piece of Messiaen’s, written for Loriod, to play. “I thought, well he’s sitting there, why not. I mean he should like to hear his own piece played. There was a risk of course, but if I could pull it off ... my wonderful French teacher Jean-Paul Sevilla had taught it to me and so I played it and, well, they gave me the prize.”

Hewitt met them both after the competition at Roy Thomson Hall (and laughs lustily recalling Loriod trying to get Hewitt to give her some of the fingerings Hewitt had used for the piece). Some 14 years later Loriod was in London, after Messiaen had died, and they met up again. She remembered every piece I had played at that competition, Hewitt recalls. Later Loriod sent her the score for Turangalila “with a wonderful letter I keep tucked in it. I regret never learning it in time to play it for her.”

Trasimeno, where Hewit mounts her annual seven day festival, also plays a key role in the magical web of interconnectedness that Hewitt seems able to spin for herself. Her upcoming recital at Koerner Hall January 9 with Anne Sofie von Otter is a case in point. “Was your own festival the first time you played with von Otter?” I ask. “It was. In fact it was the first time we had met. I was looking for a singer that year to do Respighi’s Il Tramonto for mezzo-soprano and string quartet and I had seen she had recorded it and I knew that she was with my same agency in London, so I thought well she can only say no so why don’t I risk it and ask her and we can do a recital together.” The rest, as they say, is a little bit of history.

Hewitt chooses all the artists for the festival, always some she has worked with and some she would like the chance to. She plays in every concert herself. “That’s one of the great pleasures of this festival for me” says Hewitt. “I don’t think I would do this festival unless I played. I would let somebody else do it, it’s too much work! So the playing is my reward.”

A huge repertoire of chamber music (which Hewitt has) makes the whole thing slightly easier. “I still learn fairly quickly. And also carefully. I mark things carefully in my scores so if I haven’t looked at a piece for ten years I pick up my score and it’s there, you know, at least the markings are there to go by. I might change a lot of things but the basis is still there.”

And since we are talking about revisiting scores, I ask about whether she would like to revisit some of the recordings in her now complete canon of Bach. “Oh sure” she replies. “I already have recorded the Well-Tempered Clavier twice.” She describes what she sees as the key differences in the two recordings. Things like elasticity and a wider range of colour. “I had a piano teacher in Oregon write to me and say ‘I have my students listen to your earlier recording because the later one is more free, and if they played it like that they would get marked down in their exams.’ (laughs) But I prefer the second. A lot of the new elasticity and colour comes from the fact that I started working on Fazioli pianos after my first recording of it. It expanded my imagination for colour. But you know, the older you get, I was just thinking this today, playing Beethoven, the older you get the more freedom you can put into music. First of all I suppose you have more authority and so you are not scared at all about what people are going to say. It doesn’t matter any more. You know, you can put on a metronome to see a tempo but you can’t play a whole Beethoven sonata with a metronome going. You see how it really has to follow the lines and the breathing. So yeah, one has to be open. It’s interesting to see how one develops with age.”

And since we are talking about revisiting scores, I ask about whether she would like to revisit some of the recordings in her now complete canon of Bach. “Oh sure” she replies. “I already have recorded the Well-Tempered Clavier twice.” She describes what she sees as the key differences in the two recordings. Things like elasticity and a wider range of colour. “I had a piano teacher in Oregon write to me and say ‘I have my students listen to your earlier recording because the later one is more free, and if they played it like that they would get marked down in their exams.’ (laughs) But I prefer the second. A lot of the new elasticity and colour comes from the fact that I started working on Fazioli pianos after my first recording of it. It expanded my imagination for colour. But you know, the older you get, I was just thinking this today, playing Beethoven, the older you get the more freedom you can put into music. First of all I suppose you have more authority and so you are not scared at all about what people are going to say. It doesn’t matter any more. You know, you can put on a metronome to see a tempo but you can’t play a whole Beethoven sonata with a metronome going. You see how it really has to follow the lines and the breathing. So yeah, one has to be open. It’s interesting to see how one develops with age.”

It will be interesting to see, indeed. She already has, she confides, one booking for the year 2020, although she is not at liberty right now to say what it is. So stay tuned. I will.