With “Jazz After Dark”, Toronto Jazz Festival strives to strike a better Yorkville balance

When I first investigated the extensive, 24-panel brochure for this year’s TD Toronto Jazz Festival, I was struck by the phrase “Jazz After Dark,” which appeared as one of the many thematic concert categories that the TJF used to shape its 2019 offerings. (Some other categories: Emerging Artists, First Plays, Educational Programs, CBC Music and JUNOS 365, and a “musical celebration” of “gospel, jazz and hip hop” on Bloor Street.) I’d spoken to TJF Artistic Director Josh Grossman in May about the festival’s 2017 shift from Nathan Phillips Square to Yorkville, and the coincident severance of links to the many clubs that used to present music under the auspices of the festival, albeit with no real administrative oversight from the TJF offices; during our conversation, Grossman had mentioned that there would be more nocturnal options in and around Yorkville, so that festival patrons could easily move from outdoor stages (whose days typically finished by 9:30pm) to nearby indoor venues (at which performances began at 10pm).

When I first investigated the extensive, 24-panel brochure for this year’s TD Toronto Jazz Festival, I was struck by the phrase “Jazz After Dark,” which appeared as one of the many thematic concert categories that the TJF used to shape its 2019 offerings. (Some other categories: Emerging Artists, First Plays, Educational Programs, CBC Music and JUNOS 365, and a “musical celebration” of “gospel, jazz and hip hop” on Bloor Street.) I’d spoken to TJF Artistic Director Josh Grossman in May about the festival’s 2017 shift from Nathan Phillips Square to Yorkville, and the coincident severance of links to the many clubs that used to present music under the auspices of the festival, albeit with no real administrative oversight from the TJF offices; during our conversation, Grossman had mentioned that there would be more nocturnal options in and around Yorkville, so that festival patrons could easily move from outdoor stages (whose days typically finished by 9:30pm) to nearby indoor venues (at which performances began at 10pm).

TJF’s goal, then, was clear: work with local bars and restaurants to create a kind of pop-up ecosystem of late-night jazz venues, in order to create a fuller, more all-encompassing experience for patrons who would – at least theoretically – be able to seamlessly transition from out- to indoor shows, all the while feeling as though they were still participating in activities that were comfortably within the festival. Given the location, this is a more daunting task than it might seem. For those who may not know: though Joni Mitchell may have sung about the way “music comes spilling out into the street” in the area during the late 1960s when it provided a comfortable home to artists, bohemians, and other members of the contemporary Canadian counterculture, Yorkville does not currently have an abundance of live music venues (it is possible, however, to purchase “handcrafted bohemian moccasin boots,” currently on sale for $458.43 at Free People, a local boutique). (The Pilot is something of an exception: while it is not a full-time music venue, it does host a weekly jazz series on Saturdays, although it was not a festival venue this year as it was last year.)

And so – being of relatively sound mind and body, having an overarching interest in Toronto jazz in general and the TJF specifically, and, most importantly, looking for any excuse to get out of my apartment and not spend another evening contemplating the horrifying inevitability of my eventual descent into the endless silent void, I decided to check out the TJF’s “Jazz After Dark – Presented By Mill St. Brewery.” My goal: attend a show at each of the four night-time venues, and attempt to assess whether the TJF’s evening offerings hang together and feel linked, both to one another and to the festival as a whole. Briefly put: does the TJF succeed in creating the kind of ineffable festive affect that, while difficult to plan and implement and control, constitutes an immediate and palpable shared experience for festival attendees, from the most ardent local jazz fan to the friend of a friend who was dragged along to the show and whom I heard asking aloud (hand to God), “isn’t Miles David [sic] the ‘Wonderful World’ guy?” More briefly: does the “Jazz After Dark” portion of the festival feel, well, festive?

Mill Street Late-Night Jam at Proof Bar

As in previous years, the jam – a central component at most major Canadian jazz festivals – was held at Proof Bar at the InterContinental Hotel, located opposite the ROM on Bloor Street. Hotel bars seem to provide the de facto location for Canadian jazz festival jams; hotel-bar-pricing on drinks notwithstanding, the choice seems logical. The InterContinental is something of an upper-middle class hotel, with large washrooms, crisply-uniformed staff, and the kind of stark marbled lobby that would come standard with, say, a starter mini-mansion in Thornhill. The bar area is fairly large, and is mirrored by an even larger back patio; in my two visits to the jam, both areas were full. With the exception of two of its ten sessions, the jam was hosted by bassist Lauren Falls. Falls is a confident, experienced jazz player, and was also adept at managing the jam’s attendant duties. (In addition to playing as much as is needed for your particular instrument, hosting a jam also requires you to meet with prospective jammers as they arrive, keep the ever-shifting ensemble organized, and keep track of tunes, all the while maintaining some semblance of consistent set lengths; it’s a bit like being both server and chef simultaneously.) Between my two visits to the jam, I took in a combined total of three and a half sets of music, all of which were interesting, entertaining, and indicative of the high level of musicianship in Toronto. Most of the musicians I heard seemed to be Torontonians who had come specifically to play, as opposed to musicians (local or otherwise) who had played in the festival and were stopping off for a post-gig nightcap. At one point, a couple in attendance got up and started swing dancing; more on this later.

Hemingway’s Restaurant and Bar

I know I joked about the moccasins, but Yorkville is much more like The Distillery than it is, say, the Upper East Side, and most of its dining and shopping options are geared more towards the visiting sub- and exurbanite than towards the demonstratively wealthy. Hemingway’s – which, like The Pilot, contains a number of distinct rooms, including a never-unbusy rooftop patio – is more typical of the area than a bar like Proof, and features local craft beer priced at a reasonable $8.50 for a 20oz. pint (because, as the drink menu reads with no hint of irony, “SIZE MATTERS!”). I went to Hemingway’s on Saturday, June 29, and started things off by eating some nachos and drinking a 20oz. pint on the aforementioned rooftop patio with some friends, including JUNO-award-winning saxophonist/comedy enthusiast Allison Au, who was gracious enough to hang out with me on that particular evening, and my brother Sean, who has not won a JUNO, and whose knowledge of modern comedy is middling at best. After paying our reasonable bill, we went downstairs to watch guitarist Margaret Stowe play with her trio. Stowe – a fluid, technically-accomplished guitarist, whose playing pairs folky lyricism with an athletic grace – was holding court on the main floor. It was a beautiful, warm night, Hemingway’s was beyond full, and staff members were never seemed anything but polite and good-natured about everything in what, as far as I could see, was a pretty good venue.

Sassafraz Restaurant

After watching Melissa Aldana’s set on the Cumberland mainstage, van-owner/bassist Mark Godfrey and I tried to go to Sassafraz, but it was busy, and it was impossible to secure a table close to the band. Happily, the Sassafraz windows were wide open, and we were able to enjoy the music while sitting at a table in the Village of Yorkville Park (as it is named on the TJF brochure).

Later, while the band at Sassafraz was playing a 32-bar standard, an aggressive man stood close to us and yelled “Really?! The blues, in Yorkville, the richest neighbourhood in the city? Nice, reaaaaal nice.” He moved away quickly, so I did not have time to tell him my theory about how Yorkville is really more like The Distillery than it is the Upper East Side, or about Hemingway’s reasonably-priced 20oz. pints.

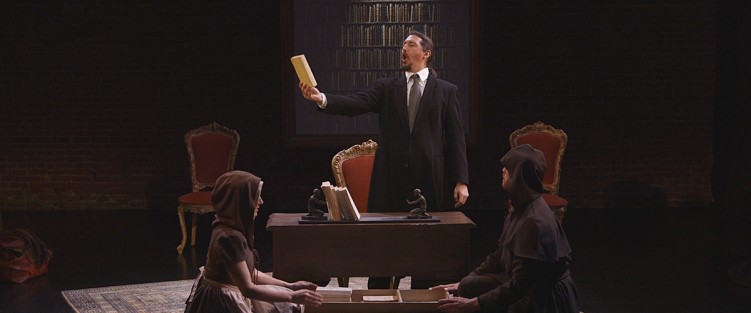

The Gatsby At The Windsor Arms Hotel

I saw two shows at The Gatsby: the violinist Aline Homzy, who played a beautiful show with bassist Andrew Downing and guitarist Jozsef Botos, and the guitarist Eric St-Laurent, who played with bassist Jordan O’Connor and pianist Todd Pentney. The Gatsby – a neo-jazz-age bar, named, presumably after the titular character of The Great Gatsby, a novel about the ultimate meaningless of decadent wealth – is located in The Windsor Arms hotel, which, as I learned online, has “been the home away from home for visiting royalty, aristocracy, stars of film and screen as well as heads of state and industry.” The décor is heavy on chandeliers and velvet. There is also a rack of fancy hats available at the entrance to the tea room, so that High Tea attendees won’t have to endure the shame of being hatless in the very room, apparently, in which Richard Burton proposed to Elizabeth Taylor for the second time, in 1967. (Some Wikipedia research indicates that Burton and Taylor were still on their first marriage by 1967, and would not divorce and remarry until 1974-75; in any case, one imagines that Taylor would have brought her own hat.) Perhaps it’s because of all of the velvet, but The Gatsby had good acoustics, and worked well, at least from a sonic perspective, for the drummer-less groups I heard. As at Proof Bar, the food and drink options, though tasty, were not inexpensive, and attendees tended to be an older, sedate crew, with the notable exception of musicians who were there to support their friends.

On Dancing

As I mentioned above, there was a moment at the jam when a middle-aged couple got up and started swing dancing (they seemed perfectly nice, and I’m sure they were having a good time, and what’s to come is really not about them, although, I suppose, it really is). This dancing occurred during someone’s solo, continued until the end of the song, and, minor occurrence though it was, proved to be a deceptively complicated moment to parse; I’ve come back to it more than a few times over the past week. Initially, it seemed nice, as any physically affirmative reaction to live music tends to seem: the couple enjoyed the music, and, like so many have before, they started to dance to demonstrate their appreciation and to participate more fully in the experience. But I soon started to wonder if it wasn’t, well, sort of disrespectful to the soloist and to the band, if not intentionally so: is a jam not meant as a dedicated space specifically for musicians, in which they have the freedom to engage in the creative play of improvisation for an audience that should not treat them, even inadvertently, as background music to another activity? But, then again, the idea that jazz is calcified art music and that audiences should be bound by strict behavioural guidelines seems damaging, and, anyway, who’s to say that the couple dancing weren’t fully invested in the band’s music, and were earnestly trying to participate and honour the art they were experiencing? And yet: did the dancing not represent, in a venue that was not set up for dancing, in front of players who were concentrating on the deeply serious act of improvising, a moment in which the audience, innocent though it no doubt was of its error, made a claim about the balance of power in the room? I don’t know; it is still hard for me to say.

And so, as to whether the “Jazz After Dark” offerings fulfilled their implicit mandate to foster the intended post-sunset festival vibe: I can’t say, really. The more pressing question seems to be related to the dancing episode, and the complicated power structure that exists between festival, venue, artist, and audience. It is, I suppose, this: who is a jazz festival for, anyway? It is certainly not just for the audience, but nor is it for the artists. It is, ideally, both, simultaneously. But how can any festival – not just the TJF – strive to better strike that balance? I don’t know, at least not yet. It’s getting late, and I need to get to bed.

The TD Toronto Jazz Festival ran from June 21 to 30, 2019, in various locations throughout Yorkville, Toronto.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached through his website, on Instagram and on Twitter.