“A beautiful thing”: Tapestry Opera’s new piano

![]()

This month, Toronto’s Tapestry Opera received its largest-ever donation—in the form of a piano.

This month, Toronto’s Tapestry Opera received its largest-ever donation—in the form of a piano.

When Ottawa-based couple Clarence Byrd and Ida Chen started thinking about downsizing earlier this fall, they decided to give up one of their pianos—a 9.5-foot, $225,000 Imperial Bösendorfer concert grand, one of the most highly-regarded concert piano models in the world. They approached Robert Lowrey (of Robert Lowrey Piano Experts), from whom they originally purchased the instrument, for advice.

“They floated the idea that it might be a beautiful thing to donate the piano to a worthy cause or organization,” says Michael Mori, Tapestry Opera’s artistic director. “Robert thought of Tapestry Opera and our Ernest Balmer Studio as a place where the performing arts community could access this wonderful instrument, and where its legacy would be ensured. As Tapestry regularly commissions and develops new works and composers, this would become the instrument upon which many of our composers would be composing new Canadian operas.”

The piano was transported this month from Byrd and Chen’s Ottawa-area home to Tapestry’s studio space in the Distillery District—no small feat. “Once it arrived in Toronto, a crane truck drove into the Distillery, just around the corner from Balzac’s Coffee and extended an impressive extending crane arm into the air, picked up the enormous piano, and then lifted it 40 feet horizontally and three stories vertically to bring it through a window that the Distillery had removed for this express purpose,” says Mori. “The process was slow but efficient—and thank God there was no wind!”

Tapestry’s first gig with the Bösendorfer will take place this October 25, in an impromptu benefit concert designed to honour Byrd and Chen’s generosity.

Tapestry’s first gig with the Bösendorfer will take place this October 25, in an impromptu benefit concert designed to honour Byrd and Chen’s generosity.

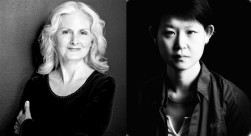

Billed as a “Disaster Relief” concert, the October 25 show will feature the Bösendorfer piano in two sets. The first, at 7pm, features several singers connected to the Tapestry community, performing selections of arias and opera and music theatre scenes, including soprano Simone Osborne, mezzo Erica Iris Huang, tenors Asitha Tennekoon and Keith Klassen, and baritone Alexander Hajek. The second, presented at 10pm by Yamaha Canada, features local piano virtuosos Robi Botos (jazz) and Younggun Kim (classical). Tickets are $30 per set, and all proceeds will be donated to Medecins sans Frontieres and Global Medic, to assist with disaster relief from recent extreme weather events in Puerto Rico, Dominica, Mexico and India.

The artists for the evening were all sourced through Facebook, explains Mori. “We were overwhelmed when our single Facebook post to solicit participation generated such an incredible response from artists willing to donate their time and talent,” he says. “It’s...a fitting way to introduce our wonderful new instrument to the community.”

After the event, the Bösendorfer will continue to be put to use in the studio, both for rehearsal purposes and for other small performances in the space. According to Mori, the new instrument—in addition to allowing for the use of the Tapestry studio as a small music venue—will be an invaluable resource for the company’s composers and artists in the years to come. “It is an instrument that will continue to inspire composers writing new opera and experimental chamber music for Canada, and in turn the audiences who come to attend exciting new works in the studio,” he says. “I can hardly wait.”

Tapestry Opera’s Disaster Relief Benefit Concert takes place at the company’s Ernest Balmer Studio in Toronto’s Distillery District, on October 25, 2017. For details, visit https://tapestryopera.com/disaster-relief-benefit-concert/

.jpg/1200px-George_Gordon_Byron_6th_Baron_Byron_by_Richard_Westall_2-area-250x326.jpg)