Music and the Movies: From TIFF 2019 to the 2020 Oscars

As movies from last fall’s Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) continue opening and the awards season advances towards Oscar glory on February 9, we’re checking in on the status of some of the films we spotlighted in our eighth annual TIFF TIPS in the September issue of The WholeNote.

As movies from last fall’s Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) continue opening and the awards season advances towards Oscar glory on February 9, we’re checking in on the status of some of the films we spotlighted in our eighth annual TIFF TIPS in the September issue of The WholeNote.

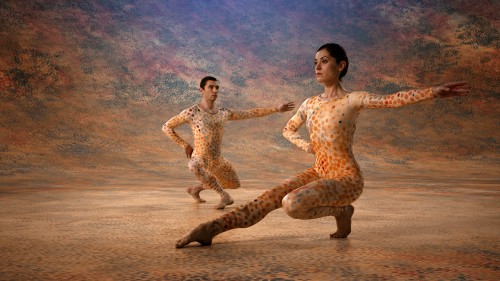

Alla Kovgan’s eye-popping, entertaining Cunningham, an invaluable look at the life and work of legendary American choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), has just opened at TIFF Bell Lightbox (with a future engagement to follow at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema). The film features 14 dances that were originally created by Cunningham between 1942 and 1972, including his first collaboration with composer/life partner John Cage, 1942’s Totem Ancestor. Cage’s singular philosophy and wit are prominently displayed throughout (as well as several other choreographed compositions) as part of the fascinating archival footage – some never seen before – that illuminates Cunningham’s early years, rehearsals, tours and “chance dance” technique. Cunningham’s own wry wit emerges in several anecdotes and it’s striking how similar the two life partners’ cadences are when they speak.

Alla Kovgan’s eye-popping, entertaining Cunningham, an invaluable look at the life and work of legendary American choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), has just opened at TIFF Bell Lightbox (with a future engagement to follow at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema). The film features 14 dances that were originally created by Cunningham between 1942 and 1972, including his first collaboration with composer/life partner John Cage, 1942’s Totem Ancestor. Cage’s singular philosophy and wit are prominently displayed throughout (as well as several other choreographed compositions) as part of the fascinating archival footage – some never seen before – that illuminates Cunningham’s early years, rehearsals, tours and “chance dance” technique. Cunningham’s own wry wit emerges in several anecdotes and it’s striking how similar the two life partners’ cadences are when they speak.

The many music and dance re-creations of music by the likes of Morton Feldman, David Tudor and Erik Satie serve as signposts to an artistic world that also contained Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and the Black Mountain poets. But as Cunningham says: “I don’t describe it, I do it.”

Recently opened, François Girard’s The Song of Names, from the book by Norman Lebrecht, is the director’s latest music-themed film after Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould and The Red Violin. It’s a sweeping historical drama, about a man searching for his childhood best friend – a Polish-born, London-raised violin prodigy orphaned by the Holocaust – who vanished in 1951 on the night of what would have been his first public performance. Not only does the movie evoke the collateral damage resulting from the Holocaust, it draws us directly to those who perished as a result of it by way of the film’s eponymous musical performance by Clive Owen as the one-time prodigy. Tim Roth also stars as Owen’s adoptive brother. Howard Shore’s indispensable score helps the film hit the right notes while Ray Chen’s world-class violin playing (for Owen) leaps off the screen.

A symbiotic relationship between two families, one rich, the other poor, is at the root of Parasite, Bong Joon-ho’s socially conscious genre-buster that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2019. An ingenious and unpredictable twist-laden black comedy overlaying a B-movie construct, its musical component by Jung Jae-il consists mostly of a solo piano melody playing against cello, guitars and orchestral strings, with an original song with lyrics by the filmmaker performed by Choi Woo-shik, an actor in the film. One of 2019’s best films as endorsed by the Academy itself, Parasite – with its six Oscar nominations for Best Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Editing, Best Production Design and Best International Film (a rebranding of the old Best Foreign Language Film category) – is highly recommended.

Ladj Ly’s Cannes Jury Prize-winning debut feature and Academy Award nominee for Best International Film, Les Misérables – set to open January 17 at TIFF Bell Lightbox – ingeniously weaves the thematic underpinning of Victor Hugo’s classic novel into an explosive contemporary narrative spotlighting France as a place of seismic political and social change. According to cinezik.org, the score by Canadian rock band Pink Noise (founded by Toronto-based Mark Sauner) is made up of consistent, unchangeable, undifferentiated electronic tablecloths that serve to maintain the film’s palpable tension. An empathetic look at the underbelly of the City of Light, life in the Paris suburbs has not been this well-portrayed since Mathieu Kassovitz’s fondly remembered La Haine (1995).

Ladj Ly’s Cannes Jury Prize-winning debut feature and Academy Award nominee for Best International Film, Les Misérables – set to open January 17 at TIFF Bell Lightbox – ingeniously weaves the thematic underpinning of Victor Hugo’s classic novel into an explosive contemporary narrative spotlighting France as a place of seismic political and social change. According to cinezik.org, the score by Canadian rock band Pink Noise (founded by Toronto-based Mark Sauner) is made up of consistent, unchangeable, undifferentiated electronic tablecloths that serve to maintain the film’s palpable tension. An empathetic look at the underbelly of the City of Light, life in the Paris suburbs has not been this well-portrayed since Mathieu Kassovitz’s fondly remembered La Haine (1995).

Nominated for two Oscars (Best International Film and Best Actor), Pedro Almodóvar’s superb new film, Pain and Glory, which bursts with autobiographical references, deals with creativity in a most novel way. It’s the story of a film director, Salvador Mallo (a graceful, subtle, nuanced Antonio Banderas), who is blocked creatively and consumed by physical pain: tinnitus, wheezes, headaches of all kinds; and what he calls pains of the soul – anxiety and tension. When we first meet him, he’s in a swimming pool trying to alleviate his back pain by exercising. He remembers, as a child, watching his mother, Jacinta (a radiant Penelope Cruz), singing A tu vera, a popular Spanish song from 1964, along with three other women, all doing their laundry at a river. It’s a happy memory, seeing his mother so joyful, and as he escapes into it, the soundtrack supports him with quizzical strings whose mysterious melody backs up the voice of a clarinet.

Alberto Iglesias has composed the soundtrack for all of Almodóvar’s films since 1995. Here, his companionable, fully integrated score is linked to what the director calls “three different atmospheres.” The first is inspired by the sunlight of the Valencian village memory; the second is linked to Mallo’s moments of pain and isolation, often adopting faster, repetitive patterns, more frantic musical movements or little tremors. The third sound, “luminous in its simple spirituality,” accompanies the scenes featuring the elderly Jacinta and grown-up Salvador, in Madrid, with the music adopting the mother’s spiritual attitude towards death. Iglesias won the Cannes Soundtrack Award for his intensely moving score – and Banderas won Best Actor at Cannes for his warm, humanistic performance. For more on the music of Pain and Glory, please see my full review at thewholenote.com.

There’s been a Stephen Sondheim shoutout (or more precisely, a sing-out) in three of this year’s TIFF-alumni, Oscar-nominated films. One such film is Noah Baumbach’s astutely observed Marriage Story, which includes Best Actor (Adam Driver) and Best Actress (Scarlett Johansson) among its six Oscar nominations. Johansson, Julie Hagerty and Merritt Wever singing You Could Drive a Person Crazy is a useful piece of the movie’s fabric, while Driver’s tour-de-force cover of Being Alive is integral to its artistic success.

Among Todd Phillips’ Joker‘s 11 Oscar nominations is Hildur Guonadóttir’s for Best Original Score. According to her website, the Icelandic-born (1982), Berlin-resident cello player is at the forefront of experimental pop and contemporary music, with the band múm, for example. In her solo work, she draws out a broad spectrum of sounds from her instrument, ranging from intimate simplicity to huge soundscapes. She has written widely for symphony orchestra, theatre, dance and film, and recently became the first woman to win a Golden Globe for Best Original Score. Like fellow Best Actor nominee Adam Driver, Joker‘s Joaquin Phoenix sings a Sondheim song (Send in the Clowns, naturally). While Phoenix’s grip on Oscar gold seems secure, Driver deserves an award for the depth of his musical sensitivity.

Rian Johnson’s Knives Out (its sole nomination is for Best Original Screenplay) included Daniel Craig’s character singing the Sondheim song Losing My Mind, which Johnson found to be a perfect analogy for the fact that Craig can’t quite figure out the mystery at the movie’s core. Baumbach, Phillips and Johnson all wrote the Sondheim songs directly into their screenplays before any footage was shot.

Finally, to complete this TIFF 2019 update, as expected, Renée Zellweger remains the favourite to win the Best Actress Oscar for her impersonation of the last months of Hollywood icon Judy Garland’s life in Judy.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.