Music and the Movies: Never Look Away

![]()

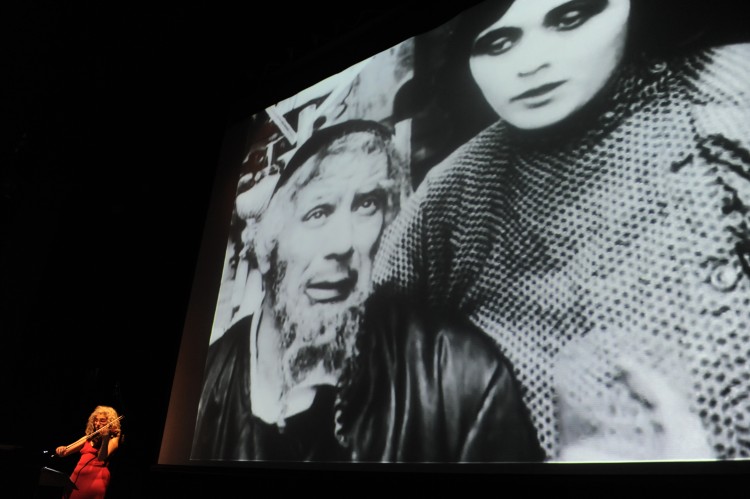

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Never Look Away – nominated for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Cinematography Oscars – paints a vast canvas chronicling the turbulent times in Germany from 1937 to the mid-1960s. It’s loosely based on the life of famed German artist Gerhard Richter but as it hits some major historical notes of the mid-20th century – Nazism, Communism, master-race eugenics and the Berlin Wall – it does so in the context of its central character Kurt’s love for two women, both named Elisabeth.

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Never Look Away – nominated for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Cinematography Oscars – paints a vast canvas chronicling the turbulent times in Germany from 1937 to the mid-1960s. It’s loosely based on the life of famed German artist Gerhard Richter but as it hits some major historical notes of the mid-20th century – Nazism, Communism, master-race eugenics and the Berlin Wall – it does so in the context of its central character Kurt’s love for two women, both named Elisabeth.

As a child, Kurt was under the thrall of his aunt, Elisabeth May, who encouraged his love of art. Indeed, the film opens in 1937 when the two of them attend the Dresden exhibit of decadent art (immaculately and beautifully rendered by the director and his legendary cinematographer Caleb Deschanel). Kurt once watched his aunt play Bach’s lovely Sheep May Safely Graze (from Cantata No.208) on the piano in the nude. (Not since Luis Buñuel’s Phantom of Liberty has the instrument been so artfully exploited.) It was her last moment of freedom. As she is taken away to be institutionalized, composer Max Richter’s post-minimalist score picks up on the Bach for an apt variation, recurring later when Kurt is at art school. The second Elisabeth, a fellow student at the Düsseldorf Academy, is the daughter of a notorious gynecologist, Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch) who was responsible for the death of Kurt’s aunt.

As a child, Kurt was under the thrall of his aunt, Elisabeth May, who encouraged his love of art. Indeed, the film opens in 1937 when the two of them attend the Dresden exhibit of decadent art (immaculately and beautifully rendered by the director and his legendary cinematographer Caleb Deschanel). Kurt once watched his aunt play Bach’s lovely Sheep May Safely Graze (from Cantata No.208) on the piano in the nude. (Not since Luis Buñuel’s Phantom of Liberty has the instrument been so artfully exploited.) It was her last moment of freedom. As she is taken away to be institutionalized, composer Max Richter’s post-minimalist score picks up on the Bach for an apt variation, recurring later when Kurt is at art school. The second Elisabeth, a fellow student at the Düsseldorf Academy, is the daughter of a notorious gynecologist, Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch) who was responsible for the death of Kurt’s aunt.

Koch, who was one of the key cast members in Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 Oscar-winner The Lives of Others, plays the villain in the new film. Koch’s relationship with the director is highly collaborative and he has described his character Professor Seeband as a monster. “He is ice-cold and domineering. But what is truly monstrous about him is that he is convinced he is doing the right thing. There is no feeling of wrongdoing, no sense of guilt. He does what he does because for him there is absolutely no alternative.”

Koch, who was one of the key cast members in Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 Oscar-winner The Lives of Others, plays the villain in the new film. Koch’s relationship with the director is highly collaborative and he has described his character Professor Seeband as a monster. “He is ice-cold and domineering. But what is truly monstrous about him is that he is convinced he is doing the right thing. There is no feeling of wrongdoing, no sense of guilt. He does what he does because for him there is absolutely no alternative.”

Henckel von Donnersmarck’s work with Richter was crucial. “[Richter’s] orchestral piece November [from 2002’s Memoryhouse] was the leitmotif for the film,” the director said. “It accompanied me throughout the entire filming and editing… He is a man of deep knowledge and great wisdom. His music has true healing power and is always incredibly beautiful.” By 1940, Elisabeth’s impending sterilization is underlined by a wrenching, ominous moment in the score. The end of WWII is played out to Handel’s Dixit Dominus.

Though nothing in Never Look Away rises to the level of November, Richter’s post-minimalist shards of emotionalism serve to buttress the complex relationships between the painter, the eugenicist and the two women who link them.

While Never Look Away is just now (February 22) opening in Toronto, two other Best Foreign Language Film nominees I profiled in The WholeNote’s September issue are still going strong in local theatres as the Academy Awards loom on February 24.

Pawel Pawlikowski’s epochal love story Cold War, nominated for three Academy Awards – Foreign Language Film, Cinematography and Direction – stands out for its cinematic artistry and fervour. Cold War begins and ends in Poland, with stops in Paris, East Berlin and Split, Yugoslavia as it journeys from 1949 to 1964. Wiktor and Zula’s love is deep and true but subject to the political vagaries of the era it inhabits. Both are musicians who meet through music (of which there is a wide variety, from traditional Polish folk to 1950s jazz). Pawlikowski depicts it with rigorous attention to detail. Filmed in stylish, enhanced black and white, with compelling performances by Joanna Kulig and Tomasz Kot, Cold War succeeds at every level.

Pawel Pawlikowski’s epochal love story Cold War, nominated for three Academy Awards – Foreign Language Film, Cinematography and Direction – stands out for its cinematic artistry and fervour. Cold War begins and ends in Poland, with stops in Paris, East Berlin and Split, Yugoslavia as it journeys from 1949 to 1964. Wiktor and Zula’s love is deep and true but subject to the political vagaries of the era it inhabits. Both are musicians who meet through music (of which there is a wide variety, from traditional Polish folk to 1950s jazz). Pawlikowski depicts it with rigorous attention to detail. Filmed in stylish, enhanced black and white, with compelling performances by Joanna Kulig and Tomasz Kot, Cold War succeeds at every level.

The music credits for Cold War are a treasure trove of traditional Polish folk music, with almost two dozen excerpts; the jazz side features Coleman Hawkins, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Kulig and Kot doing Gershwin’s I Loves You, Porgy. What wraps up this musical odyssey? A few moments of Glenn Gould playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations. It’s all a not-to-be-missed cinematic experience, due in large part to its crucial musical component.

Nadine Labaki’s emotionally potent film Capernaum, about a 12-year-old Lebanese boy who sues his parents for giving him life, won the Jury Prize at Cannes last year. It’s another worthy nominee contending for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Labaki’s husband Khaled Mouzanar produced the film and composed the score. To fit what Mouzanar called “the poverty and rawness of the subject,” he wrote a “less melodic score than usual using dissonant choral melodies that seem to disappear before they can be grasped, as well as synth-based electronic sonorities.” Crucially, he chose not to “underline or highlight emotions that were already sufficiently intense.”

Nadine Labaki’s emotionally potent film Capernaum, about a 12-year-old Lebanese boy who sues his parents for giving him life, won the Jury Prize at Cannes last year. It’s another worthy nominee contending for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Labaki’s husband Khaled Mouzanar produced the film and composed the score. To fit what Mouzanar called “the poverty and rawness of the subject,” he wrote a “less melodic score than usual using dissonant choral melodies that seem to disappear before they can be grasped, as well as synth-based electronic sonorities.” Crucially, he chose not to “underline or highlight emotions that were already sufficiently intense.”

Any one of these Oscar contenders would make for ideal viewing in the days leading up to Sunday’s awards ceremony. And for months and years in the future for that matter.

Never Look Away opens at TIFF Bell Lightbox on February 22. Cold War and Capernaum continue their Toronto runs.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.