Jennifer Taylor has a knack for programming. Music Toronto’s artistic producer and general manager admitted in a recent chat that while she has “a tiny reputation for piano recital debuts, just say that I am lucky.” We met in her office in an older building high above the city’s downtown core. Glancing at the list of pianists who have made their local debuts under Taylor’s watch over the last 25 years, many of the names jump out: Pascal Rogé, Misha Dichter, Nikolai Lugansky, Markus Groh, Andreas Haefliger, Simon Trpčeski, Piotr Anderszewski, Steven Osborne, Arnaldo Cohen, Alexandre Tharaud, Till Fellner, Peter Jablonski and Benjamin Grosvenor, who returns to the stage of the Jane Mallett Theatre on October 13, a mere 19 months after his memorable debut there in 2014. Conceding that she doesn’t usually gamble on pianists as young as Grosvenor, she said: “He was the real thing.”

Jennifer Taylor has a knack for programming. Music Toronto’s artistic producer and general manager admitted in a recent chat that while she has “a tiny reputation for piano recital debuts, just say that I am lucky.” We met in her office in an older building high above the city’s downtown core. Glancing at the list of pianists who have made their local debuts under Taylor’s watch over the last 25 years, many of the names jump out: Pascal Rogé, Misha Dichter, Nikolai Lugansky, Markus Groh, Andreas Haefliger, Simon Trpčeski, Piotr Anderszewski, Steven Osborne, Arnaldo Cohen, Alexandre Tharaud, Till Fellner, Peter Jablonski and Benjamin Grosvenor, who returns to the stage of the Jane Mallett Theatre on October 13, a mere 19 months after his memorable debut there in 2014. Conceding that she doesn’t usually gamble on pianists as young as Grosvenor, she said: “He was the real thing.”

Grosvenor’s exceptional talent was widely revealed at 11 when he won the keyboard section of the BBC Young Musician of the Year. At 19, shortly after becoming the first British pianist since the legendary Clifford Curzon to be signed by Decca, he became the youngest soloist to perform at the First Night of the Proms. The venerable magazine Gramophone bestowed its “Young Artist of the Year” on him in 2012.

The youngest of five brothers, his piano-teacher mother shaped his early musical thinking. He divulged in a 2011 YouTube video that he decided at ten to be a concert pianist and wasn’t fazed at all by playing on the BBC shortly thereafter. Only when he became more self-aware at 13 or 14 did he suffer some anxious moments. An excerpt on the piano of Leonard Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety followed, the musical core of which he expressed beautifully, both literally and figuratively, before adding, “The pieces you play the best are the ones you respond to emotionally.”

Just a week after his appearance in the Last Night of the Proms at Royal Albert Hall in London on September 12, the now 23-year-old pianist took time out from his busy schedule to generously answer several questions I sent him via email. Such a high profile concert was just the latest in a career that has seen the spotlight shine on this extraordinary performer for more than half of his life.

The WholeNote: Your recital in Toronto last year at the Jane Mallett Theatre was a revelation. I was impressed by your sensitivity and tonal palette; by the way you seemed to dig deep into the heart of each piece. When I heard you play the Schubert Impromptu Op.90 No.3, you reminded me of one of my favourite pianists, Dinu Lipatti. Has he been an influence on you?

Benjamin Grosvenor: I admire a great many fellow pianists – both alive and not – and Lipatti is one of them. With all great pianists, and particularly with such pianists of the golden age, there is something that is distinctive in all their performances, whether of Bach, Liszt or Ravel, which is indelibly theirs – their own sound or ‘voice’ at the piano. Lipatti and his interpretations remain ideals of technical and musical perfection, but there are a great many other pianists whose playing I admire for various distinct reasons – Horowitz, Moiseiwitsch, Cherkassky, Schnabel, Bolet etc. They too all have their own ‘voices’ and touch me in different ways.

WN: I’d like to focus on the program for your upcoming Toronto concert. Please tell me what attracts you to the Mendelssohn Preludes and Fugues.

Grosvenor: The Mendelssohn pieces are underrated works, not very often played. Each of the six in this set is masterfully constructed and has emotional qualities of its own. All feature preludes with beautiful melodic material – reminiscent of the Songs without Words – and wonderfully constructed fugues, translating an archetypal baroque form into Mendelssohn’s own language. The Fugue of the E minor is a sombre work that builds in intensity as it processes. It bears a resemblance to the Franck that comes later in the program, in that the troubled quality in the music – softly spoken at first, later forcefully uncompromising – is only resolved at the very end, with a triumphant chorale, and a soothing coda in the major key. The Fugue of the F minor takes the fugue to virtuosic heights, with a frenetic energy throughout.

WN: With the Bach-Busoni Chaconne and the Franck Prelude, Chorale and Fugue, you seem to be continuing the baroque spirit of the Mendlessohn. The Franck is a major work that is seldom heard live here. What is your relationship to it? When did you first discover it? I found fascinating Stephen Hough’s note that Alfred Cortot described the Fugue in the context of the whole work as “emanating from a psychological necessity rather than from a principle of musical composition.”

Grosvenor: I have loved the Franck since hearing the Cortot recording in my teens. It is a deeply spiritual work, and Stephen has written in that article more eloquently about its religious connotations and significance than I can do so here. When I heard it for the first time, I was struck by its raw emotion, and the scale of its journey. The chorale builds from fragile sobs to a massive outcry of pain. The Fugue sustains such intensity, the only reprieve from which is in the quietly soothing return of the chorale theme. It builds again to the climax where the themes combine – an explosive “working out” of the melodic strands. Only at the end is there a sense of resolve. It ends with joy, and with bells.

WN: And I see that the baroque theme continues with Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin. What do you find to be the essence of that piece?

Grosvenor: All the pieces of the first half involve composers taking elements of baroque music and presenting these in their own musical tongues. The same is true of the Ravel, where the inspiration is the dance suites of the French Baroque. Each movement is dedicated to friends of the composer who died in the Great War, and while some of the music was thought uncharacteristically joyous for such dedications, to much of the music (the fugue, forlane, menuet) there is a veiled sadness, and melancholic beauty.

WN: Two of Liszt’s Venezia e Napoli from the Années de pèlerinage, Second year, Italy, are song-based, the other, the Tarantella is a wild dance. In a 2013 webcam/YouTube video at the time of your Singapore appearance, you talked about your great interest in recordings made by pianists like Moriz Rosenthal, Ignaz Friedman, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Shura Cherkassky and Vladimir Horowitz in the early half of the 20th century. “Their primary concern was in imitating the voice especially in Romantic repertoire,” you said. I look forward to hearing how you will perform those Liszt pieces given that statement. Is that how you see Venezia e Napoli?

Grosvenor: The Liszt works are certainly inspired by songs, and specifically some of the popular melodies that Liszt heard himself on the streets of Italy. Venezia e Napoli is, it seems to me, quite an underrated and underperformed work. The Gondoliera is a beautifully atmospheric setting of a melody (a Venetian folk song) capturing the lapping water and sparkling rivulets (and perhaps towards the end, birdsong) in the canals of Venice. The Canzone, based on a melody by Rossini, has a sense of deep foreboding, with throaty melodic lines and an underlying tremolo in the left hand. The Tarantella is perhaps the most famous of the set and is a wonderful example of the colours, textures and moods that can be created on the piano.

WN: Why are you so drawn to those pianists of the first half of the last century? How has listening to them informed the way you play? Are there contemporary pianists you admire? Do you have any musical heroes who have inspired you?

Grosvenor: I do have an interest in pianists of the past, both for the absolute merits of their performances and because one is potentially exposed to expressive and pianistic tools that may have disappeared from the modern lexicon. There are a great many contemporary musicians I also admire, but I’d rather not mention names for fear of leaving out others...!

WN: You’ve been in the public eye for more than half your life, since your first appearance on the BBC. How do you reconcile your public and private life?

Grosvenor: I don’t think I’ve ever really found it difficult to reconcile “public” and private life. Life as a classical musician is not quite like that of people who have high profiles in other fields, and it is easy to descend into the background. It is a demanding profession though, and involves a lot of work. The challenge is to reconcile private life and professional life. Good planning and time management is key!

The vital middle: According to Taylor, Music Toronto occupies “the vital middle” in the city’s classical music life. It’s hard to imagine a better concert or more exciting artist than Grosvenor to open their 44th season. Season highlights include two noteworthy string quartet debuts – Cuarteto Casals and the Artemis Quartet – the return of favourites Marc-André Hamelin, the St. Lawrence Quartet and the Gryphon Trio, as well as appearances by the superb JACK Quartet and Quatuor Ébène, the welcome return of pianist Steven Osborne, and debuts by Peter Jablonski and the young-Polish-quartet-on-the-rise, the Apollon Musagète Quartett.

Taylor books 12 to 18 months in advance after a varied process that ranges from surfing the Internet and gleaning concert programs from around the world to listening to advice from other presenters and audience members. A recommendation from an audience member of a Schubert recording by the Cuarteto Casals two years ago led to their upcoming October 22 recital (with a program including Mozart, Kurtag and Ravel). The Berlin Philharmonic Quartet recommended the Artemis Quartet to Taylor several years ago; she finally booked their April 14, 2016 concert after trying since 2012. An amateur pianist and old friend of Taylor’s recommended Jablonski five years ago. Two years ago, something related to the Apollon Musagète Quartett came in the mail. Intrigued by the name, Taylor investigated and closed the deal for their November 26 recital. “It’s always guesswork,” she said about the process. “But at the end of the first movement you know. Sometimes it’s extraordinary.”

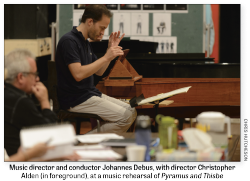

COC Rehearsal. At the end of week one of rehearsal for the COC’s world premiere of Barbara Monk Feldman’s Pyramus and Thisbe, a small group of invited media witnessed a fascinating process unfold in the company’s headquarters on Front St. Baritone Phillip Addis and mezzo-soprano Krisztina Szabó sat in front of a tall, massive, bright yellow cinder block wall, three metres from conductor Johannes Debus, separated only by their music stands amidst the vastness of the rehearsal room. Addis, his eyes wide open this early in the rehearsal process tells Debus that when he first learned his part as Pyramus, his approach was very rigid; now that he’s more familiar with the piece he feels it can be more jazzy. Debus replies that when the score calls for only one note (and a long one, at that) there’s nowhere to hide. “It’s necessary to discover the Frank Sinatra (or the Ella Fitzgerald) in all of us,” he said.

COC Rehearsal. At the end of week one of rehearsal for the COC’s world premiere of Barbara Monk Feldman’s Pyramus and Thisbe, a small group of invited media witnessed a fascinating process unfold in the company’s headquarters on Front St. Baritone Phillip Addis and mezzo-soprano Krisztina Szabó sat in front of a tall, massive, bright yellow cinder block wall, three metres from conductor Johannes Debus, separated only by their music stands amidst the vastness of the rehearsal room. Addis, his eyes wide open this early in the rehearsal process tells Debus that when he first learned his part as Pyramus, his approach was very rigid; now that he’s more familiar with the piece he feels it can be more jazzy. Debus replies that when the score calls for only one note (and a long one, at that) there’s nowhere to hide. “It’s necessary to discover the Frank Sinatra (or the Ella Fitzgerald) in all of us,” he said.

There really are three characters in this new work, Debus told us, but paradoxically Pyramus, Thisbe and the chorus (plus the orchestra) also merge into one (quite slowly). “Maybe we lose the sense of time,” he pointed out. Another one of Monk Feldman’s qualities is that very difficult-to-perform sustaining of notes. Ultimately, Debus finds the opera to be a piece in suspended time. Performing it properly is a lot about breathing.

“Ninety percent of the time we’re like curators in a museum. [Working on a new opera] puts certain things for us as interpreters into perspective. The exchange between creative minds is absolutely … an adventure as none else. A Canadian-composed-opera premiere is something quite remarkable.

“Monk Feldman’s writing is basically orchestral. It works a lot with the natural decay of orchestral music … It’s kind of a meditation on this old Pyramus and Thisbe myth, kind of fragmented.”

It’s hard not to overstate Debus’ versatility and engagement in the process. In addition to much back and forth banter with director Christopher Alden, his involvement with the singers was direct and supportive. He sang the chorus cues in Pyramus and played impeccable harpsichord in Il combiattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, one of two Monteverdi works that complete what should be a memorable program with the Monk Feldman.

The TSO Decades Project begins October 21 and 24 with Debussy’s enduring masterpiece La Mer and the rare treat of hearing Vaughan Williams’ A Sea Symphony live. Peter Oundjian conducts and Erin Wall and Russell Braun are the vocal soloists in the Vaughan Williams. The first two decades of the 20th century shaped what we are today and the orchestra will be showcasing them in a series of six concerts and cross-disciplinary programming this season. In partnership with the Art Gallery of Ontario, The Decades Project will explore the similarities and differences of the two art forms in the space where music and visual art meet. The concerts are enhanced by pre- and post- concert talks guided by AGO curators and performances by The TSO Chamber Soloists. The project continues October 28 and 29 with Sibelius’ joyous, richly romantic Symphony No.2 and Bartók’s youthful Violin Concerto No.1. Finnish-born John Storgårds, recently named principal guest conductor of the NAC, conducts; the versatile Benjamin Schmid is the soloist in the Bartók.

Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society highlights this month include: four concerts by the Attacca String Quartet, October 29, 31 and November 1, as they continue their traversal of Haydn’s complete string quartets; and the star-studded Trio Arkel in works by Haydn, Osterle, Rosza, Dvořák and Beethoven, November 8.

QUICK PICKS

Oct 11 Angela Hewitt performs works by Scarlatti, Bach, Beethoven, Albeniz and De Falla at the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts, Kingston.

Oct 15 The versatile Afiara String Quartet is joined by harpist Caroline Léonardelli and bassist Joseph Phillips in the first concert of the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto’s 118th season.

Oct 15 The world-class Takács Quartet performs Haydn, Shostakovich and Schubert’s Death and the Maiden at the Perimeter Institute, Waterloo.

Oct 18 Stewart Goodyear performs the famously difficult, legendary Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No.3 with Orchestra Toronto at the George Weston Recital Hall.

Oct 18 Chamber Music Hamilton has assembled a topnotch aggregation of string players including COC Orchestra concertmaster Marie Bérard and superstar cellist Shauna Rolston in a program of sextets by Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky.

Oct 20 The always interesting Afiara String Quartet is joined by guitarist Graham Campbell for “Ritmos Brasileiros” a free noontime concert fusing chamber music, jazz and the Brazilian choro at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre.

Oct 25 The justly celebrated American pianist Simone Dinnerstein returns to Koerner Hall in a program that includes Schumann’s delightful Kinderszenen and Bach’s French Suite No.5.

Oct 27 Ensemble Made in Canada begins their Schumann piano quintet project in the Music Building of Western University, London.

Oct 30, 31 The exciting young American pianist Orion Weiss, a protégé of Emanuel Ax (and part of the Ax-curated Piano Extravaganza earlier this year in Toronto), performs concertos by Mozart and Bach with the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony.

Oct 31 The dynamic TSO principal violist, Teng Li, performs music by Hindemith, Paganini, Brahms and others with Meng-Chieh Liu, piano, at the Fairview Library Theatre.

Oct 31, Nov 1 The tireless Stewart Goodyear and the Niagara Symphony Orchestra perform the complete piano concertos of Beethoven twice within 24 hours, inaugurating Cairns Hall, St. Catharines.

Oct 31 Constantine Kitsopoulos conducts the TSO string section in a live accompaniment to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, one of the greatest films ever made. Take advantage of this unique event pairing Bernard Herrmann’s music, so cinematic on its own, with the movie it helped make iconic.

Nov 1 Mooredale Concerts presents “Vivacious Violins” with Nikki Chooi and Timothy Chooi, violins, and Jeanie Chung, piano, playing music by Prokofiev, Sarasate and Saint-Saëns.

Nov 1 The assiduous Emanuel Ax performs works by Beethoven, Dussek and Chopin at the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts, Kingston, and at the Flato Markham Theatre, Nov 4.

Nov 4 The New Orford String Quartet plays two of Beethoven’s finest quartets, Op.59 No.3 and Op.130 with the Grosse Fuge finale, at Walter Hall.

Nov 5 Members of the COC Orchestra showcase the range of the inimitable Haydn string quartets in a free noontime concert at the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre.

Nov 5 Music Toronto’s 44th season continues with the Cecilia Quartet in a program that ranges from Mozart and Mendelssohn to Nicole Lizée.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.