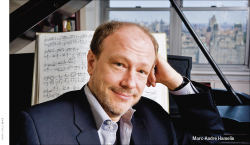

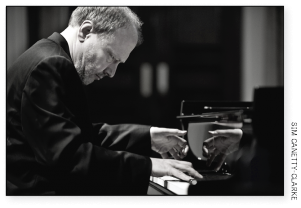

Marc-André Hamelin In Conversation

Marc-André Hamelin had just come in from a walk when he answered his phone. I had called him mid-November in advance of his Music Toronto recital next January 5. “It’s my first concert of the year, actually,” he said. I opened our conversation by congratulating him on his recent inclusion in the Gramophone magazine Hall of Fame, a group of 25 pianists that ranges from legends like Rachmaninov, Richter, Rubinstein, Horowitz, Michelangeli, Gould and Lipatti to contemporaries such as Argerich, Pollini, Perahia, Uchida, Hough and Schiff. I asked whether he feels a kinship with any particular pianist, living or dead.

Marc-André Hamelin had just come in from a walk when he answered his phone. I had called him mid-November in advance of his Music Toronto recital next January 5. “It’s my first concert of the year, actually,” he said. I opened our conversation by congratulating him on his recent inclusion in the Gramophone magazine Hall of Fame, a group of 25 pianists that ranges from legends like Rachmaninov, Richter, Rubinstein, Horowitz, Michelangeli, Gould and Lipatti to contemporaries such as Argerich, Pollini, Perahia, Uchida, Hough and Schiff. I asked whether he feels a kinship with any particular pianist, living or dead.

“I grew up listening to the great pianists of the past, historical recordings,” he answered, before moving into an explanation of his influences in a nutshell. “If there’s any heritage to what I do, any sort of influence or maybe source for a lot of what I have done, you’d have to look for it there. However, this is what I was exposed to at the very beginning due to my dad and those were his listening preferences. But later on I became much more aware and much more respectful of the written note. So I think that what I do today is sort of a happy mix of the two. Or let’s say a judicious use of all these elements, of both of these aspects.”

Not since Glenn Gould has a Canadian pianist had such a global impact as Marc-André Hamelin. Just as Gould’s interpretation of Bach revolutionized the way we heard his music, Hamelin made musical sense of late 19th and early 20th century pianist-composer romantic music so fiendishly difficult it had seemed lost until he unearthed it. As the years passed, Hamelin’s repertoire has broadened to embrace more traditional repertoire.

I wanted to know what considerations went into programming the January concert, which consists of a late Mozart sonata (K576), Liszt’s Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude and Venezia e Napoli and Schubert’s last sonata (D960). “Well,” he said, seizing on the sonata. “The Schubert B Flat is an easy one. I could play it in every single concert till the day I die. I wouldn’t be unhappy.”

I reminded him of a 2009 interview with Clavier Companion where he spoke about having played the sonata already in public for nine or ten years, yet still found wonderful things in it. He had said that the piece was so fresh he doubted he would ever tire of it, even if he could include it in all of his recitals. “That’s true,” he laughed. “I’m glad things haven’t changed, because it just shows you the power of that particular work.”

When I tried to get him to account for his attraction to it, he was surprisingly forthright. “It’s one of those pieces with which I’d rather have it remain a mystery. Because the more words you try to put to it, the more difficult it becomes to know exactly what it is that attracts me to it so much. I feel exactly the same way about the last three Beethoven sonatas. Which I’ve played quite a bit as well.”

Not only that, I reminded him, but he had performed Schubert’s glorious final sonata in his Koerner Hall recital earlier this year in March, persuasively venturing into the Schubertian sound world using an unflinching romantic approach. “Aha! Not only that,” he repeated. “But I also played it many years ago in, I think, Walter Hall, to inaugurate a new piano. So it will be my third performance of it in Toronto. I hope people won’t get sick of my performance.” But then his memory deepened: “Oh, I also played it in North York. That, as you can imagine, was quite a few years ago. I remember because Tamara Bernstein reviewed it very favourably.” It was the one time he played the George Weston Recital Hall.

I told him I was curious about what drew him to certain pieces, and he was careful to give a balanced response: “If I say that I’m attracted to involved harmonies and dense textures, I don’t want to exclude the fact that I like very simple textures and simple harmonies as well. I’m attracted equally to something like the music of Franck or Busoni, or something like that, which can be really rather thorny and harmonically involved, but I also love the pieces from the collection of On the Overgrown Path of Janáček which have very few notes indeed but still express worlds of emotions. So basically, I guess it amounts to what is expressed and not necessarily how it is expressed. Human emotions have been the same throughout man’s history; it’s only the ways of expressing it – the language, musically speaking, I mean – that has changed and of course, evolved a great deal.”

Later, listening to the Janáček on his 2014 Hyperion recording of it, I was struck by the emotional richness his playing conveys. For the most part, the music may be simple and subdued but there are sudden bursts of power that he unleashes in a storm of notes in Our Evenings, the first movement. Moving along the path, as it were, a brooding Slavic interlude mixes moods and colours in They chattered like swallows, lingering tantalizingly. The quiet contemplative beauty of Good night leads into the dark, angular world of Unutterable anguish before reaching the sublime essence of melodic purity with In Tears.

I asked how Hamelin goes about learning a new piece. He answered by detailing what he doesn’t do, that is, use recordings. He prefers to go directly to “what the composer is asking,” which is the score. Imperfect as that may be as a vehicle for their thoughts, he believes it’s the only way composers have of communicating their pieces.

“I won’t necessarily interpret everything that’s on the page. I will try to rationalize: If, for example, there’s a miscalculation or if they didn’t express exactly what they wanted. I’m a composer myself and that has enabled me, and I’m sure, other composer-interpreters could say the same thing. It has enabled me to feel a little closer to the creators of the works I perform because I know a little bit more how they felt at the moment of creation and what the task is of trying to notate your intangible thoughts into a system of notation that is open to interpretation.”

When I asked whether Hamelin finds thinking about a piece away from the piano to be a valuable learning tool, I was hoping to strike a chord, but the answer was far more detailed than I could have imagined. And remarkably timely:

When I asked whether Hamelin finds thinking about a piece away from the piano to be a valuable learning tool, I was hoping to strike a chord, but the answer was far more detailed than I could have imagined. And remarkably timely:

“Absolutely. I experienced it just a few minutes ago when I was taking a walk before you called. I was thinking about something that I’m working on right now. And because I’m not busy producing the sound at the piano I can think about the music in a more pure way. And I can get a little more effectively to the essence of the music. And plenty of things will suggest themselves – little emphases – I mean, a counterpoint will jut out for example, tempi will be a little bit more right if I’m just thinking purely about the music. Architectural things will become clearer. Textural things will become clearer. A whole host of practice can be done away from the piano. That’s generally not something that is really well known.

“Most parents think that once their kids have accomplished their two hours at the piano that’s it, they don’t have to do anything else. But thinking about the music is at least as valuable as practising at your instrument. Because after all, you’re doing this not to impress the populace, you’re doing this to learn how to communicate a message. And you have to know what message to communicate. You have to have something to say.”

I started to ask about Hamelin’s close relationship with his father but before I could finish my question Hamelin interrupted to say, “You know, he actually died 20 years ago today, as a parenthesis, November 17, ’95.” Hamelin agreed that he was lucky to have had a father like that, who, although a pharmacist by profession, was a gifted amateur pianist, whose talent as his son quickly put it, “came out of absolutely nowhere because his parents weren’t musical.”

I had read somewhere that his father was his first teacher. “In a sense,” he said. “My first official teacher was a local lady who I had for four years after which my dad enrolled me in Vincent d’Indy School. But essentially I have started to list my dad as one of my teachers simply because he oversaw a lot of my development. I could always talk to him and ask him things. And he offered suggestions. When he didn’t like what he heard, he said so.”

Hamelin agreed that his father, with his penchant for composer-pianists, and his recordings, which he played all the time, had a considerable influence on his musical taste as a child. It was hard to get recordings and sheet music in those days when “Canada was still a little bit of a cultural desert.” He told me that at the time his father was very intrigued by Leopold Godowsky’s music but it was very difficult to get, almost nothing was available, “and now it’s all available with a few clicks because it’s on IMSLP [imslp.org].”

From listening to his father’s record collection Hamelin “definitely got a sense, predominantly, of a great and sometimes excessive interpretive freedom.” “You know,” he added, “at the time, musicology wasn’t really the science that it is today. Back then true respect for the printed note still had a long way to come. So I grew up with the sentiment that one could do with the music as one pleased [he laughs], which isn’t too good if you’re playing things like Beethoven or Bach or Chopin or Mozart. But later on [after he emigrated to the U.S. in 1980 to study with Harvey Wedeen at Temple University] playing with other people and also with my teacher’s influence, I got to respect the printed score a lot more. And also the fact that I write music myself gets me to appreciate a lot more the toil and trouble composers go through.”

Charles Ives’ first teacher was his father. Among other exercises, he would play a song on the piano and have his young son sing it in a totally different key. So I found it fascinating that Hamelin, with his own special father-son relationship, would have chosen Ives’ Concord Sonata as the first LP he bought “with his own pennies,” as he once put it. It was John Kirkpatrick’s second recording of the piece, recorded in 1968. Hamelin bought it in 1975. He gave me a typically detailed answer to my question of how he chose to buy that particular LP:

“I really started to be intrigued by contemporary music. A few years earlier my dad had gotten a subscription to the Piano Quarterly and it featured reviews of scores at the beginning. And they reproduced the first page of almost everything. So there was everything from beginners’ pieces to the most advanced avant-garde scores. And those, the latter, really made an impression on me, you know, the ways of notation. And he also subscribed to Clavier magazine. In October ’74 there was an Ives special issue because it was the centenary of his birth. And there were a lot of articles and there was a discussion of the Concord Sonata, among other things. And it really intrigued me. At the same time I saw that a local record store had the Kirkpatrick recording, so I picked it up. $7.98. I still remember. Tenth of June, 1975. I remember it because it’s the only year I ever kept a diary.”

He bought a lot of contemporary recordings after that – Stockhausen, Cage, Boulez, Xenakis – everything he could lay his hands on. “A lot of bargain records.” And “Oh my God, yes,” he answered when I asked if he was still buying records. He elaborated:

“You know, I shop a lot second-hand because first of all, regular record shops are dying and I don’t like the fact that one can’t browse online really, physically. So I much prefer second-hand shops and I buy vinyl at least as much as CDs these days. This is beside the fact that vinyl with young people has made a resurgence. But also because there are tons of things still to be found. And I’m not only talking classical music. I mean I can buy anything from classical music to comedy records to improvisation to noise to electronic music to all kinds of things.”

When I asked if there is anything in particular he listened to for pleasure, he replied that there is so much in his collection to catch up on that he almost never listens to a recording twice. And he added something he deemed very important: “I was once asked who my pianistic heroes are and I had to answer: the score. Because as much as we have fantastic recordings, tons of fantastic recordings throughout history, throughout the 20th century, the score is still my ideal.”

Trying to get a sense of the immensity of his collection I asked how extensive it was. Again, his answer took me by surprise. “It’s hard to quantify. The only thing I can quantify right now with any certainty is that I’m waiting for some funds to convert a garage into a sizable music room. And my sheet music collection right now is in 97 clear plastic bins. So that gives you an idea.”

Of course, with over 70 CDs of his own to his credit, I was curious as to how he chose what to record. Hamelin volunteered that from the beginning of their association over 20 years ago, Hyperion has always been very open to what he wanted to do. “Of course, they were a little cautious at the beginning as far as more standard repertoire because I really wasn’t known for that, even though I have been playing standard repertoire all the time,” he said. “It’s just that my recorded repertoire was very maverick-y up to when I started with them. But gradually, I’m very happy to say, that they were willing to give me more freedom as far as standard repertoire. And that really started with the Haydn recordings that they let me do [recorded in December 2005; released in March 2007]. I had to do a little bit of persuading, but it’s really paid off,” he added.

I had just recently listened to his Haydn Sonatas Vol. 3 and felt compelled to tell him that I found it to be totally seductive and smooth. I said that it reminded me of sipping a local wine in Beaune at lunch, which made him laugh. Because it was so elegant and supple. Which made him laugh even more and thank me.

Among his own compositions on his Etudes CD is Cathy’s Variations, written for and about his domestic partner, Cathy Fuller, a classical music host for WCRB FM 99.5 in Boston. I found the theme to be very sweet and the experience of listening to it, coupled with a personal history of having heard Hamelin in concert several times during the last 20 years, compelled me to say that he seemed more relaxed in concert over the last several years. “Join the club,” he immediately interjected. “A lot of people have said that. Which couldn’t please me more. She’s an extraordinary person. She’s also trained as a pianist. A remarkable musician.”

Coming from a man who is a remarkable musician himself, that’s more than a compliment to the woman he complements. In his liner notes to Cathy’s Variations, Hamelin wrote that the piece is “purely the work of a man in love…inspired by…my true soulmate, who fascinates me more with each passing day.”

Marc-André Hamelin appears in recital for Music Toronto at the Jane Mallett Theatre, St. Lawrence Centre, on January 5, 2016. The following month he returns to perform Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No.1 with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, February 25 and 27 at Roy Thomson Hall.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.