![]() The 21C Music Festival, now in the third edition of its guaranteed five-year run, was originally conceived as an opportunity to celebrate creativity, collaboration and commissioning, all critical elements in the coinage of new music in the 21st century. This year’s edition of the festival will do just that. Over five days and seven concerts featuring 28+ premieres, its audiences’ ears will be abuzz with sounds that capture fresh creative ideas and directions. Among the seven, three projects stood out in particular for me, all of them offering world premieres and, viewed together, revealing the overall scope and intent of the festival – almost as though they were a single 3-part invention titled Throat Singing – Darkness – Koto & Sho.

The 21C Music Festival, now in the third edition of its guaranteed five-year run, was originally conceived as an opportunity to celebrate creativity, collaboration and commissioning, all critical elements in the coinage of new music in the 21st century. This year’s edition of the festival will do just that. Over five days and seven concerts featuring 28+ premieres, its audiences’ ears will be abuzz with sounds that capture fresh creative ideas and directions. Among the seven, three projects stood out in particular for me, all of them offering world premieres and, viewed together, revealing the overall scope and intent of the festival – almost as though they were a single 3-part invention titled Throat Singing – Darkness – Koto & Sho.

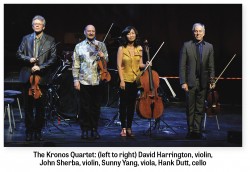

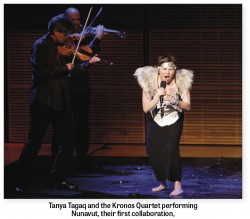

THROAT SINGING: Imagine having the capacity to sound like a string quartet, all through using your throat and voice. That’s exactly how David Harrington, Kronos Quartet’s first violinist, described the exhilarating and ferocious throat singing of Tanya Tagaq. Although Tagaq was raised on the lands of the Inuit people in the Arctic village of Cambridge Bay in Nunavut, the traditional sounds of throat singing were unknown to her while growing up. In fact the first time she heard it was while studying at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, on tapes sent to her by her mother. Fascinated by the sound, she taught herself the technique by singing in the shower.

THROAT SINGING: Imagine having the capacity to sound like a string quartet, all through using your throat and voice. That’s exactly how David Harrington, Kronos Quartet’s first violinist, described the exhilarating and ferocious throat singing of Tanya Tagaq. Although Tagaq was raised on the lands of the Inuit people in the Arctic village of Cambridge Bay in Nunavut, the traditional sounds of throat singing were unknown to her while growing up. In fact the first time she heard it was while studying at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, on tapes sent to her by her mother. Fascinated by the sound, she taught herself the technique by singing in the shower.

It was another recording (a January/February 2003 fRoots Magazine compilation CD) that led to a meeting between Tagaq and the legendary Kronos Quartet. While travelling home on a plane some 13 years ago, Harrington was listening to that CD. Track 1 was Youssou N’Dour. Track 18 of 18 was something called “Ilgok” by Tanya Tagaq. Harrington was transfixed. “It was an incredible vocal performance,” he told me in a recent interview. “Although I had known about Inuit throat singing for 30 years, I had not heard anything like it. It sounded as if it were two to three people singing at the same time. After listening to it about 30 times in a row, I knew I had to be in touch with her and figure out a way to do music together.” They eventually met in Spain when Tagaq, who was living there at the time, came to a Kronos soundcheck and performed for them. “Knocked out” by what they heard, the quartet resolved to make music with Tagaq.

It was up to Harrington to figure out how this was going to happen. The night before their first rehearsal together in Whitehorse, Yukon, he still didn’t know how it was going to work, but finally at 5am he had an idea. Using his granddaughter’s crayons he made five coloured squares – one for each performer – with the idea that each player would musically interpret their own colour. Later they added more coloured squares and found a way to connect the sounds that each person came up with. This first collaboration, Nunavut, will be one of a full program of works performed by Kronos in the opening concert of the 21C festival on May 25.

Kronos is renowned for charting a wildly different musical path for the string quartet as a chamber ensemble, and for their work in mentoring emerging artists. This vision continues at the heart of Fifty for the Future, their latest project, designed to create a repertoire of training works for young string quartets to introduce them to contemporary music. Starting in this current concert season, Kronos will be commissioning 50 new works by 25 women and 25 men over five years. Four of the works from Year One will be performed on the May 25th concert, including the world premiere of a new commission from Tagaq.

Reflecting on the Nunavut project, along with other pieces Kronos and Tagaq have created together, Harrington says: “Tanya is an amazing composer, even though she doesn’t necessarily think of herself as a composer, she just does music.” Harrington so values his experience of having worked with Tagaq that he invited her to be one of the first ten composers to participate in the Fifty for the Future project, because their collaboration over the years has been one aspect of his own musical life and that of Kronos that he wants to be sure other musicians, especially young musicians, are able to experience.

Why a vocal performer as a model for string quartet players, I asked? “Because it sounds to me like she has a string quartet in her throat,” Harrington replied. “And because Tanya is very connected to nature and the way she thinks of music is a natural part of her life, it’s effortless, even though she works very hard.”

For anyone who has had the experience of hearing Tanya Tagaq perform, this statement will ring true. Something exudes off the stage that seems rare yet also distantly familiar, like a calling back to our primal roots. I asked her about the nature of this place it seems she goes to when performing. “It’s not so much a place I go to as a place I come to,” she responded. “It’s a freedom, a lack of control, an exploration, and I’m reacting to whatever happens upon the path.” She spoke about the limits we put upon ourselves as humans, and exclaimed “Things need to happen to raise us to live in the moment!” This place she comes to “requires being in the present, for when you are in the present, it doesn’t matter what else is happening, what’s going to happen or what has happened. That’s what I like about improvisation – it’s all new and it’s all happening.”

She also loves collaborating, describing the process as like adding different rooms to a store. In her collaboration with regular band members, percussionist Jean Martin and violinist Jesse Zubot, she said it’s like “going to see really good friends to have a conversation. We have our own language that we speak, and when there’s a gap in time of not being together, I can feel this anticipation and urge to speak again.” She described singing with the improvisational Element Choir directed by Christine Duncan, who are increasingly accompanying her on stage and will be included on her next recording due for release later this year, as “like having a wind from behind, or someone pushing really really hard in a super positive way.”

Tagaq’s Fifty for the Future collaboration with Kronos is titled Snow Angel-Sivunittinni (meaning “the future children”). Tagaq met with the quartet in a recording studio in San Francisco where she recorded two improvisations –a single track first, then a second improvisation laid down on top of that one. Longtime Kronos collaborator, trombonist/composer Jacob Garchik then transcribed Tagaq’s studio vocal tracks for the quartet, spreading the two layers out amongst the four players, after which Harrington then had a further idea – wouldn’t it be wonderful if she came up with four vocalized introductions to the piece, each about one minute long and each interpreting a different member of Kronos. One of these four “Snow Angels,” as the introductions are called, is spontaneously selected each night the work is performed. (Harrington is hoping that his will be the one chosen for the Toronto premiere.) Final element of the work: Tagaq will add an additional live improvised layer to the piece during the performance!

Tagaq’s Fifty for the Future collaboration with Kronos is titled Snow Angel-Sivunittinni (meaning “the future children”). Tagaq met with the quartet in a recording studio in San Francisco where she recorded two improvisations –a single track first, then a second improvisation laid down on top of that one. Longtime Kronos collaborator, trombonist/composer Jacob Garchik then transcribed Tagaq’s studio vocal tracks for the quartet, spreading the two layers out amongst the four players, after which Harrington then had a further idea – wouldn’t it be wonderful if she came up with four vocalized introductions to the piece, each about one minute long and each interpreting a different member of Kronos. One of these four “Snow Angels,” as the introductions are called, is spontaneously selected each night the work is performed. (Harrington is hoping that his will be the one chosen for the Toronto premiere.) Final element of the work: Tagaq will add an additional live improvised layer to the piece during the performance!

Garchik has collaborated on more than two dozen Kronos projects to date; his work will also be in evidence in two other pieces that Kronos will perform on the May 25 program – by composers Geeshie Wiley and Laurie Anderson. And speaking of the May 25 program, Harrington was, as he described it, “smiling from ear to ear. There are works by seven female composers and each one of them is so different from the other, it will be like this incredible meeting of unforgettable people.” The program includes three other commissions from Year One of the Fifty for the Future project, as well as two earlier works by composers who are scheduled to be part of Year Two of the project: Canadian Nicole Lizée’s piece from 2012, The Golden Age of the Radiophonic Workshop, which pays homage to the pioneers of electronic music in Britain, and the aforementioned piece by Laurie Anderson, Flow, arranged in 2010 from a track on her Homeland album.

The key feature of the Fifty for the Future project will be the easy availability of all the commissioned works. Scores, parts and recordings by Kronos of each of the pieces will be accessible for download from the Kronos website, with the first five pieces being available now. Tagaq’s piece will be ready in about six months and will include an interview, a video and the original studio recordings as auxiliary material. After the entire project is completed, it will be an incredible mosaic of music by composers from around the world destined to introduce future string quartets to the diversity of contemporary musical ideas.

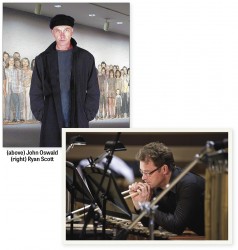

DARKNESS: Imagine yourself entering a completely dark concert hall in a line, conga style, with your hands on the shoulders of the person in front of you, like a small train of people, ushered by someone using an overhead highway system complete with roads and intersections. Following “driving directions” received from the head usher who is outside the hall with a map, your usher is feeling their way along this overhead tracking system to deliver you to your specific seat. And it’s complete darkness, with absolutely no light being emitted from exit signs, computers, soundboards or windows.

This is how “Blackout”, a late-night 21C concert, May 27, created by Toronto-based composer and saxophonist John Oswald, will begin. Once the audience is seated, what will unfold will be a one-hour concert of music by Oswald, including a 21C new commission, intermingled with quotes and perhaps intact works from Oswald’s previous repertoire. The late-night concert will be more like a variety show, he told me in our recent phone conversation. Not surprisingly, the 10:30pm concert sold out as of mid-April, so an additional concert is being planned starting at 8pm.

Performers will be spatially distributed throughout the room, intermingled with the audience. The piece is scored for up to 50 musicians, including members of Radiant Brass, the Element Choir, a percussion quartet, piano, electroacousmatic elements and three secret singers, all interwoven over the hour. The identities of the singers will be secret in order to create the surprise element of “what is that that I am hearing? Since there will be a celebrity element, people will be surprised at WHO they are hearing,” Oswald said.

Creating a work where all the performers will be in the dark requires different compositional strategies, as there will be no scores. Oswald selected musicians who are used to improvisation “as they know how to navigate through unknown musical territory by listening rather than staring at a score. Simple procedures will be used, so that once you know the seed idea, you just need to listen your way through it.” Even the Element Choir, who are used to performing with visual cues coming from conductor Christine Duncan, will have to rely exclusively on listening. Duncan already uses some sonic cues in the choir’s regular performances, such as singing specific musical gestures or notes to different sections of the choir and her voice is often part of the overall choral soundscape. These features will be the starting place for their role in “Blackout.”

Creating pieces to be heard in a completely dark environment is not new to Oswald. Back in 1976, he spent a summer working with R. Murray Schafer and the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University in BC. Out of that context he began thinking about the best way to listen to something, and how a concert could be set up so that the attention is focused on sound. His first darkness concert was performed at the Western Front that summer in collaboration with Marvin Green, and from there, the two created other events in Toronto at the Music Gallery, the Mirvish Gallery and at Comox Theatre. Oswald adds: “Marvin and I called that field of inquiry and those concerts PITCH, a reference to pitch, but also to the idea of pitch black.”

Oswald admits that a concert in the dark may not be for everyone, but it will be made clear beforehand what to expect. His goal though is for it to be a wonderful and joyful listening experience. Towards the end of our conversation I asked him whether he thought we listen differently when we are not visually stimulated. To answer, he relayed the experience in one of his earlier darkness concerts when photographer Vid Ingelevics came in with an infrared camera to take photos. What the pictures revealed was that many people had their eyes open and were staring off in all directions, especially looking upwards. People were cuddled together and the various poses were unlike any audience Oswald has seen. I guess the best answer is to come and experience for yourself.

KOTO & SHO: Imagine a sound palette with no boundaries between Eastern and Western instruments, where the traditional Japanese koto (a zither-like instrument) and the sho (a mouth organ) blend seamlessly with an oboe, viola and clarinet. Welcome to the world of the UK-based Okeanos ensemble. Known for their fascinating mix of Japanese and Western instruments, they are actively engaged in commissioning and interacting with the Japanese contemporary music world. Two members of Okeanos will join Continuum Contemporary Music for a May 26 21C concert titled “Japan: NEXT.”

KOTO & SHO: Imagine a sound palette with no boundaries between Eastern and Western instruments, where the traditional Japanese koto (a zither-like instrument) and the sho (a mouth organ) blend seamlessly with an oboe, viola and clarinet. Welcome to the world of the UK-based Okeanos ensemble. Known for their fascinating mix of Japanese and Western instruments, they are actively engaged in commissioning and interacting with the Japanese contemporary music world. Two members of Okeanos will join Continuum Contemporary Music for a May 26 21C concert titled “Japan: NEXT.”

The idea for the concert began when Continuum artistic director Ryan Scott travelled to Japan in 2014. There he was introduced to the music of the younger generation of Japanese composers, and was inspired to put together a program of their music. One of the younger composers Scott researched was Dai Fujikura, currently living in the UK. It was through Fujikura’s five-piece Okeanos Cycle, written between 2001 and 2010 that Scott discovered Okeanos; three of the five pieces will be heard at 21C. Interestingly, even though Fujikura lived in Japan for the first 15 years of his life, he had never heard nor been in contact with traditional Japanese instruments (a curious parallel with Tagaq never having heard throat singing until she moved to Nova Scotia). When Okeanos approached Fujikura to write music for their ensemble, he had to learn about the instruments from the British players. However, wanting to avoid exoticism, Fujikura brought his own energetic and distinctly European style to this hybrid of sound worlds.

Another composer Scott came into contact with while in Japan was Misato Mochizuki, whose piece, Silent Circle, written for a 21-string koto will be performed at the festival, but not without a few snags along the way. Because the koto player from Okeanos had to cancel her appearance, Scott reached out to Mitsuki Dazai, the leading koto player in North America, to perform the piece. But Dazai travels with a 13-string koto, a problem for the proper performance of Silent Circle. The solution? Dazai has developed a way of getting the 21 different pitches on the 13-string koto by splitting the strings on the harmonic points. (Apparently this has caused quite a stir in the koto community.)

The program will also include two world premieres by Canadian composers Hiroki Tsurumoto and Michael Oesterle. Oesterle’s work is a new arrangement of a piece he originally wrote in 2010 for marimba and the virtuoso koto player Kazue Sawai, and for which Oesterle has subsequently made other arrangements for Continuum’s instrumentation. However, for this event, he has pulled out all the stops: another arrangement which takes advantage of all the available instruments. Look on Glass, scored for two shos, koto, harp, guitar and marimba as well as Continuum’s regular sextet, gives Oesterle the opportunity to combine western and eastern instruments in his own unique way.

This portrait of three 21C concerts is just the tip of the iceberg, with so much more to explore. The festival continues to be a unique opportunity to take in the diversity and genre-bending trends of how music is currently being created and conceived. Similar to the mosaic of music that will eventually end up in Kronos’ Fifty for the Future project, the 21C festival series, spread out over its five years, will be creating its own unique tapestry of collaborations, creative exchanges, and experimentations. It’s too early at this stage to see what its long-term effects will be, but hopefully the festival will stand as a significant venture in creating the attention that contemporary music deserves.

Wendalyn Bartley is a Toronto-based composer and electro-vocal sound artist. sounddreaming@gmail.com.