But for a few instances of momentary curiosity of a few brave, or possibly foolhardy, musicians, modern concert audiences might have never heard the sound of historical instruments at all. A great case in point is the pianist Malcolm Bilson’s discovery of historical keyboards back in 1969.

When Bilson decided to give a concert on “Mozart’s piano” the result was very nearly a disaster. “I have to admit now that I really couldn’t handle the thing at all,” Bilson said in a lecture. “I must be the least gifted person for the job: my hands are too big, and I don’t have the necessary technique such an instrument required. In trying to operate this light, precise mechanism, I really felt like an elephant in a china closet. But I kept at it all week and practised hard and after several days began to notice that I was actually playing what was on the page. Suddenly I found that I really didn’t need much pedal and that the articulative pauses actually made the music more expressive.” Concert audiences and audiophiles should certainly be grateful that Bilson persevered – he was one of the first 20th-century fortepianists, and without him it’s doubtful we’d even hear a fortepiano today.

When Bilson decided to give a concert on “Mozart’s piano” the result was very nearly a disaster. “I have to admit now that I really couldn’t handle the thing at all,” Bilson said in a lecture. “I must be the least gifted person for the job: my hands are too big, and I don’t have the necessary technique such an instrument required. In trying to operate this light, precise mechanism, I really felt like an elephant in a china closet. But I kept at it all week and practised hard and after several days began to notice that I was actually playing what was on the page. Suddenly I found that I really didn’t need much pedal and that the articulative pauses actually made the music more expressive.” Concert audiences and audiophiles should certainly be grateful that Bilson persevered – he was one of the first 20th-century fortepianists, and without him it’s doubtful we’d even hear a fortepiano today.

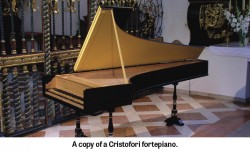

We’re also kind of fortunate Bilson opted to try using a fortepiano in the first place – the instrument itself is something of an oddity. Even to its inventor, it couldn’t have been considered to have much potential – it was initially a research and development project for the wealthy Florentine Medici family by the Italian instrument maker Bartolomeo Cristofori way back in 1700.

Cristofori fit the stereotype of the eccentric inventor quite well indeed. As if inventing a new keyboard instrument wasn’t ambitious enough by itself, Cristofori also tried making harpsichords out of ebony as well as building his own upright harpsichords from designs by other inventors. It’s not known what Cristofori’s patrons thought of the instrument, but it was likely positive, as he continued to develop his invention over the next 20 years and the technology and building of pianos spread across Europe. By the 1730s, J.S.Bach had a chance to play one and recommended the builder make changes (which out of respect for the composer’s expertise, he duly did, much to Bach’s satisfaction). Still, the harpsichord was generally regarded as the superior, or at least, the more affordable, of the two keyboard instruments until the century’s end.

In the classical era, Haydn composed for the harpsichord for most of his early career, and wouldn’t buy a fortepiano until he was in his 50s, but Mozart, being 20 years younger, would come to favour the fortepiano exclusively. Just 50 years after Haydn’s death, pianos were becoming louder, more uniform in sound and more durable – and with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, mass-produced in factories and available to a middle-class market.

Andrea Botticelli: The fortepiano revival owes much to that first adventurous concert Malcolm Bilson gave in 1969, and there’s been a steady increase in fortepiano players since, but there hasn’t been a professional fortepianist who’s called Toronto home until now. Andrea Botticelli is a recent graduate of the University of Toronto’s doctoral music program in piano performance who has decided to specialize in fortepiano and Classical repertoire. Like Bilson, Botticelli found playing a different instrument to have an almost immediate effect on her interpretation. “Playing a fortepiano was such an eye-opening experience,” Botticelli says. “All the performance issues that are such a struggle on the modern piano – texture, clarity, balance between the hands – become so much easier on the fortepiano.” According to Botticelli, all the exacting details that composers like Mozart and Schubert took such care in writing, all those little slurs, phrase markings and articulations that pianists struggle with, were actually written for the old 18th- and 19th-century instruments, and a modern Steinway can’t really negotiate the difficult terrain as easily.

“So much of what I was trying to add in terms of expression is really inherent on this instrument,” she says. “Once I really started playing the fortepiano, I wondered how I could have gone through a whole undergraduate degree without ever having heard one.” Botticelli will be making her solo debut later this month at the Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts on September 24 at 6:15 pm, playing fantasies by Mozart, Haydn and Hummel, as well as a Mozart piano sonata.

It’s really about time there was a resident fortepianist in the GTA, and the fact that Botticelli is willing to base herself in Toronto is yet another sign that the local arts scene has grown to world-class size. There’s been a steady creep of historically inspired practice around the world since the 1970s from medieval/renaissance repertoire through the Baroque period and well into the 19th century, and professional fortepianists have been starting to pop up in major cities around the world in recent years. It’s as if an extinct species has been found again in the wild and is starting to propagate. Like audiences in London, Amsterdam and Vienna, Torontonians will now be able to hear period performances of classical and romantic keyboard music on this compelling period instrument.

Christophe Coin: There are few musicians worldwide as accomplished as Christophe Coin. A gambist, cellist and protégé of Jordi Savall since the mid-70s, Coin has gone on to record over 50 albums ranging from Gibbons’ consort music to Schumann’s cello concerto. Coin also directs the Ensemble Baroque de Limoges and is the cellist for Quatuor Mosaïques, so he’s quite adept in conventional baroque and classical repertoire. It will be exciting to see him as both musical director and soloist for Tafelmusik in their upcoming concerts October 5 to 9 at Trinity-Saint Paul’s Centre. It’s clear from this program that Coin is no slouch as a soloist – he’ll be playing both a Boccherini and a Haydn concerto – and he’ll also be leading the orchestra in symphonies by C.P.E. Bach and Dittersdorf – repertoire that both Tafelmusik and Coin excel at. If you’re at all interested in classical music, this is a concert well worth attending.

Rezonance: Finally, if you’d like to hear a chamber music concert this month, or just want to get out of the concert hall for a change, consider making it out to hear my group Rezonance Baroque play the music of J.S. Bach at the CSI coffee pub at 720 Bathurst St. (home base of The WholeNote), on September 25 at 2 pm.

After Bach settled in Leipzig as the resident music director of St. Thomas’s Church, he was left without a venue to perform any of his secular compositions or chamber works. Fortunately for the master, Gottfried Zimmermann, the owner of the local café in Leipzig, was already one of the hottest music venues in town. Rezonance will perform an all-Bach program that could have easily been heard at Zimmermann’s, including a cantata he composed for the café in honour of coffee. While it’s easy to imagine Bach as overwrought, overworked, and dependent on a caffeine fix to get through the day, this concert features exciting and whimsical repertoire that shows that the brilliant composer may have had a sense of humour after all.

David Podgorski is a Toronto-based harpsichordist, music teacher and a founding member of Rezonance. He can be contacted at earlymusic@thewholenote.com.