Creative Community without Boundaries

In my story on the Festival of Arabic Music and Art (FAMA) in my October 2018 column I explored the GTA’s Arabic music scene. That festival is still in full swing, so consult our concert listings for details or visit the festival website at CanadianArabicOrchestra.ca/FAMA.

This month we are taking a peek into the world of Chinese orchestras in our midst, a form of community music-making long hidden from audiences outside its various host communities. Then we join an early world-music adapter, the American composer, percussionist and conductor Adam Rudolph as he returns to the Music Gallery to explore the implications of dastgah (melodic-modal systems) with Toronto tar player and Persian classical music advocate Araz Salek.

The Chinese orchestra

While ensemble music has been practised on a sophisticated level in Chinese aristocratic courts for some three millennia, I am referring here to the modern Chinese orchestra, as currently performed in China and overseas Chinese communities, which began its development in the 1920s, modelled on both the instrumentation of the regional Chinese Jiangnan sizhu ensemble and the organization of the Western symphony orchestra. Such orchestras use Chinese instruments divided into four sections: winds, plucked strings, bowed strings and Chinese percussion. They typically play modernized traditional music often called guoyue (literally “national music”), or adaptations of Western works.

In terms of the dawn of Chinese instrumental music in Canada, the relevant Canadian Encyclopedia entry states that Chinese emigration to Canada – specifically to the Fraser River Gold Rush in British Columbia – began in 1858, mostly from Kwangtung (Canton) Province. Already by the 1870s there were three Cantonese opera clubs established in Victoria, BC.

The production of Cantonese opera required about six instrumentalists, and this led to the founding of music clubs apart from opera clubs. These music associations, as exemplified by the Ching Won Musical Society (founded in Vancouver in 1936), performed for many types of Chinese community activities.

The Chinese community in Toronto was established around 1877, with an initial population of two laundry owners. The community grew considerably during the 20th century when, again according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, professional troupes from Hong Kong were frequently invited to perform Cantonese opera until the 1980s, when the expansion of the Chinese community provided performers for locally produced Cantonese opera, often featuring artists from abroad. [As well], local companies such as the United Dramatic Society in Toronto, the Wah Shing Music Group in Ottawa, and the Yuet Sing Chinese Musical Club in Montreal provided training and experience for Canadian performers.”

As I am a newbie to this world, I phoned Amely Zhou, an erhu musician and Chinese orchestra insider. Trained in both Chinese and Western music, she began her music studies at an early age in the city of Shenzhen, in southeastern China. “After immigrating to Canada in 2007,” she told me, “I joined the Toronto Chinese Orchestra where I served for ten years as the bowed string section assistant principal, as well as conductor of the TYCO, its Youth Orchestra.”

She pointed out that beginning with the TCO, today there appear to be four Chinese orchestras active in the GTA: Toronto Chinese Orchestra (1993- ), Ontario Chinese Orchestra (2007- ), North America Chinese Orchestra (2011- ) and Canadian Chinese Orchestra (2017- ).

“I founded the Canadian Chinese Orchestra (CCO) last year and serve as the CCO’s artistic director and conductor. We actually have three groups under the CCO banner: the Canadian Philharmonic Chinese Orchestra made up of amateur adult musicians and the Canadian Youth Chinese Orchestra (CYCO). The third group is a cadre of professional musicians who serve as section leaders. These contract artists teach our CYCO and CPCO musicians, while also performing as soloists in our concerts.”

What about the other Chinese orchestras in our region? “In 2007 the Ontario Chinese Orchestra (OCO) was founded by graduates of top-ranking Chinese music conservatories,” replied Zhou. “Led by Peter Bok, they have produced a regular series of concerts ever since.”

“More recently another performing group, the North American Chinese Orchestra (NACO), was formed by several Mandarin-speaking musicians in 2011,” added Zhou.

The TCO: Despite ample evidence of a century and a half of Chinese music making in Canada, it wasn’t until 1993 that the Toronto Chinese Orchestra was established by a group of Chinese traditional music enthusiasts. According to its website, the “TCO is the largest Chinese orchestra in Ontario and the longest running in Canada. Members include professional and amateur musicians trained in Asia as well as Canada.”

The TCO presents its next concert, “Scenic Sojourn: A night of Chinese Music,” at Yorkminster Citadel on December 1. In addition to works by Chinese composers, the TCO performs works by the emerging Toronto composers Matthew van Driel (Whiteout) and Marko Koumoulas (Reincarnation Suite), indicating an active engagement with the non-Chinese music community.

The Canadian Chinese Orchestra: Chinese orchestras in the GTA appear to be affiliated along linguistic and cultural lines, reflecting Cantonese and Mandarin origins. How does the CCO fit into this context? “In establishing the CCO I was motivated by a desire to reach out to the various Canadian Chinese communities, as well as to the Canadian public in general” said Zhou. “I believe we are Canadians first, so I wanted to include musicians from various Chinese communities, from newcomers to musicians born here.”

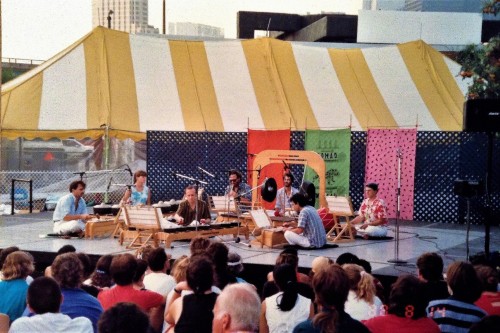

The CYCO mounted its most ambitious project to date in the summer of 2018: a five-city tour of the Cantonese region of China. “It came about through an invitation from the president of the Overseas Nanhai International Students Association,” stated Zhou, “partly funded by the Cultural Department of the government of China.”

It’s part of a trend of the GTA’s Chinese orchestras performing in the motherland, made possible through the Chinese government’s sponsorship of cultural exchange between overseas and mainland Chinese communities. It reflects 150 years of region-of-origin (Cantonese in this case) affiliations, transnational business links, and a trend of Canadian cities “sistering” with Chinese cities of similar industry focus, all connected via cultural links. For instance, both cities of Nanhai and Jiangmen, located in the Cantonese region of China and on CYCO’s 2018 tour itinerary, have sistered with the City of Markham, reflecting the commercial interests of high tech companies.

CCO’s November 17 concert at the Mary Ward Catholic Secondary School Theatre is conducted by Amely Zhou and Wang Yi. The concert features repertoire reflecting various regional Chinese folk genres. Here are some highlights.

The CCO’s young prize-winning Canadian-born dizi (bamboo transverse flute) soloist Sophie Du is accompanied by the CCO in an orchestrated Taiwanese folk song inspired by a scene of tea pickers in the Lugu mountains.

Racing Horses, an erhu standard, was composed by Haihuai Huang. Depicting horses racing on the vast Mongolian grassland it is performed by the CCO erhu section together, evoking the sound of a large herd of galloping horses. The concert closes with Flower Festival (1960s). Composed by Xuran Ye as a pipa solo, it is based on a Sichuan folk song; it has been arranged by Zhou for the CCO for this concert.

Coincidentally, also on November 17 the Music Gallery and New Ambient Modes present “Dastgah: Go: Organic Orchestra.” The concert will be curated by Araz Salek, the Toronto tar (Persian long necked lute) player, and conducted by American world music pioneer Adam Rudolph.

Rudolph embarked on a career as a jazz percussionist in Chicago in the late 1960s. He was eager however to expand his musical world view. In 1977 he travelled to West Africa to live and study music, experiencing drumming, singing and dancing, as well as trance ceremonies.

He shares on his blog that in 1978 he “lived in [trumpeter, pioneer of world fusion jazz] Don Cherry’s house in the Swedish countryside.” Cherry inspired Rudolph to “start composing and showed him about [free-jazz pioneer] Ornette Coleman’s concepts and the connection of music to nature.” Back in the USA Rudolph and kora player Jali Foday Musa Suso co-founded The Mandingo Griot Society in 1978, combining aspects of African and American music. He explored Moroccan Gnawa music in the 1980s with sintir (three-stringed bass lute) player and singer Hassan Hakmoun. His music-making and composing has continued to grow over the decades, resulting in a large number of ensemble projects, reflected in over 90 album releases.

Rudolph often sets discussions of his approach to music in a philosophical frame. Case in point, in an April 2017 Downbeat interview by John Ephland, Rudolph evocatively talks about “shooting the arrow and then painting a bullseye around it” when describing his music creation process. He also reports undertaking a rigorous study of North Indian tabla for over 15 years with leading tabla virtuoso and teacher Taranath Rao (1915-1991), crediting Rao with imparting the notion of music as a “form of yoga – the unity of mind, body and spirit…”

Founded two decades ago, Rudolph’s Go: Organic Orchestra is a culmination of a lifetime of musical and philosophical searches, embracing music forms and cosmologies from around the world. His compositional and operational modus operandi is built on a three-page score with graphic notation elements he calls matrices and cosmograms. It’s evidently been successful: over the last ten years Rudolph has conducted several dozen Go: Organic Orchestra residencies throughout Europe, North America and in Turkey.

Toronto’s Music Gallery first presented Go: Organic Orchestra in 2016, inviting 15 eclectic Toronto musicians to play under Rudolph’s direction. Araz Salek, the only musician in the ensemble whose primary background was outside of jazz or Western classical music, was particularly inspired by the experience.

Salek: Born in Iran in 1980, Araz Salek began his tar tutelage at a young age and continued studying classical radif (sets of Persian melodic figures preserved through oral tradition) with master tar musicians. He began an active performing career in Tehran.

Moving to Toronto in 2005 however blew open the doors of Salek’s strict Persian classical music training. While establishing himself in his new home, he quickly began to learn and perform with a wide variety of musicians practicing in numerous musical traditions. In addition to gigging nationally and internationally as a tar player, in 2017 he founded Labyrinth Ontario, dedicated to presenting music workshops and concerts focused on global modal music traditions.

I’ve been involved in a number of concert projects with Salek for over 12 years. I am however not personally involved in Dastgah: Go, so I called Salek late in October to get the skinny.

“Adam Rudolph’s 2016 Music Gallery concert,” he began “was a stunning experience for me. As you know I have an extensive background in Iranian classical music. When I arrived in Toronto I continued my tar practice, but also engaged with the local free improvisation scene. On occasion however, I felt lost in the midst of such freedom, particularly when compared with my own rigorous training and practice in Iranian music.

Working with Adam, on the other hand, he says, felt substantially different than playing free improv. “What really amazed me was how his use of graphic matrices defined not only tonal [and rhythmic] structures, but also freed individual musicians to make choices within them. It was the best of both worlds for me, combining the liberty of free improv with the kind of modal structures I’m most comfortable with. In that way, the 2016 concert was personally an inspiring moment. I wanted the opportunity to expand that musical experience. I made a proposal to Adam: to develop his score by including aspects of Iranian tonal systems. He agreed and our Dastgah: Go: Organic Orchestra project was born.

“The 15 Toronto musicians chosen for the November 17 concert are divided roughly into two instrumental categories: a Western group and an Iranian group. “I will be conducting a series of ear training sessions for the musicians to develop their perception of the microtonal intervals in some of the traditional Iranian modes,” Salek says. “An interesting cross-cultural instrument in our orchestra will be a retuned acoustic piano. This used to be done in 20th-century Iran, but was found to be too costly, and moreover could only accommodate a very limited number of tonal modes. We’ve revived this practice for this concert. It will prove, I think, that even an instrument with fixed tuning like the piano can be accommodated to perform with Iranian instruments.”

Rudolph’s improvisationally conducted spontaneous orchestrations will no doubt be substantially complicated – and enriched – by Salek’s Iranian contributions.

The multicultural dynamics of Dastgah: Go: Organic Orchestra aptly express Rudolph’s creative vision of our shared humanity. As he states on his website, “It is a realization of creative community in a world without boundaries; of culture as the vessel for understanding, empathy and sharing.” It’s a fitting legacy for an early adopter of a single-minded approach to world music.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.